December 16, 1971. The day Pakistani Armed Forces surrendered to the joint forces of India and Bangladesh at the Suhrawardy Uddyan. The Joint Forces’ final offensive in East Pakistan, launched in the early hours of December 4, 1971, culminated at 4:31 p.m. on December 16 with the complete surrender of four divisions of West Pakistani troops in Dhaka—marking the decisive victory that secured Bangladesh’s independence.

The Surrender That Ended the War

The surrender of Pakistani forces in Dhaka was the result of intense back-channel negotiations that began on December 15, when General A.A.K. Niazi, the Pakistani commander in East Pakistan, reached out to India via the U.S. consulate. Niazi proposed halting the fighting while keeping his troops armed and under command—an offer India firmly rejected, demanding unconditional surrender by 9 a.m. the next day.

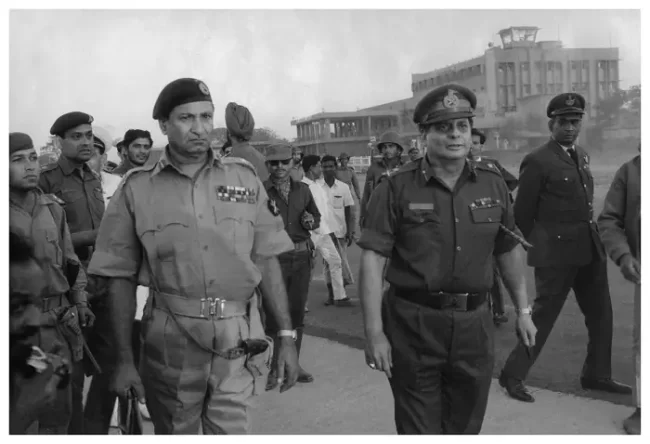

To push for resolution, India ordered a temporary bombing pause overnight. Just 30 minutes before it expired, Niazi requested a six-hour extension and invited a senior Indian officer to Dhaka to finalise surrender terms. Major General J.F.R. Jacob flew into Dhaka and, after preliminary agreements were reached, General Aurora and his delegation, including Mukti Bahini leaders, arrived to formalise the surrender.

By afternoon, joint Indian and Bengali battalions entered Dhaka, taking control as crowds of jubilant Bengalis flooded the streets. Although only part of Pakistan’s Eastern Command was stationed in the capital, Niazi had issued orders for all remaining units across East Bengal to lay down their arms—sealing Bangladesh’s victory and independence.

Witness Accounts

Siddiq Salik, Public Relations Officer, Pakistan Army

Siddiq Salik, a Pakistani military officer and author, is best known for his book Witness to Surrender, a firsthand account of Pakistan’s surrender to the India-Bangladesh joint forces on December 16, 1971. Serving as a public relations officer in East Pakistan during the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War, Salik provides a detailed and poignant narrative of the events leading to the fall of Dhaka and the creation of Bangladesh. His book offers a rare Pakistani perspective on the conflict, documenting the military, political, and human dimensions of the surrender, where around 93,000 Pakistani troops capitulated—the largest military surrender since World War II.

“The temporary cease-fire was agreed from 5 p.m. on 15 December till 9 a.m. the following day. It was later extended to 3 p.m., 16 December, to allow more time to finalize cease-fire arrangements. While General Hamid ‘suggested’ to Niazi that he accept the ceasefire terms, the latter took it as ‘approval’ and asked his Chief of Staff, Brigadier Baqar, to issue the necessary orders to the formations. A full-page signal commended the ‘heroic fight’ by the troops and asked the local commanders to contact their Indian counterparts to arrange the cease-fire. It did not say ‘surrender’ except in the following sentence: ‘Unfortunately, it also involves the laying down of arms.’

It was already midnight (15/16 December) when the signal was sent out. About the same time, Lieutenant-Colonel Liaquat Bokhari, Officer Commanding, 4 Aviation Squadron, was summoned for his last briefing. He was told to fly out eight West Pakistani nurses and twenty-eight families the same night to Akyab (Burma) across the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Lieutenant-Colonel Liaquat received the orders with his usual calm, so often seen during the war. His helicopters, throughout the twelve days of all-out war, were the only means available to Eastern Command for the transport of men, ammunition and weapons to the worst-hit areas. Their odyssey of valour is so inspiring that it cannot be summed up here.

Two helicopters left in the small hours of 16 December while the third flew in broad daylight. They carried Major-General Rahim Khan and a few others, but the nurses were left behind because they ‘could not be collected in time’ from their hostel. All the helicopters landed safely in Burma and the passengers eventually reached Karachi.

Back in Dacca, the fateful hour drew closer. When the enemy advancing from the Tangail side came near Tongi, he was received by our tank fire. Presuming that the Tongi-Dacca road was well defended, the Indians side-stepped to a neglected route towards Manekganj, from where Colonel Fazle Hamid had retreated in haste as he had from Khulna on 6 December. The absence of Fazle Hamid’s troops allowed the enemy free access to Dacca city from the northwest.

Brigadier Bashir, who was responsible for the defence of the Provincial Capital (excluding the cantonment), learnt on the evening of 15 December that the Manekganj-Dacca road was totally unprotected. He spent the first half of the night gathering scattered elements of E.P.C.A.F., about a company strength, and pushed them under Major Salamat to Mirpur bridge, just outside the city. The commando troops of the Indian Army, who were told by the Mukti Bahini that the bridge was unguarded, drove to the city in the small hours of 16 December. By then Major Salamat’s boys were in position and they blindly fired towards the approaching column. They claimed to have killed a few enemy troops and captured two Indian jeeps.

Major-General Nagra of 101 Communication Zone, who was following the advance commando troops, held back on the far side of the bridge and wrote a chit for Lieutenant-General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi. It said: ‘Dear Abdullah, I am at Mirpur Bridge. Send your representative.’ Major-General Jamshed, Major-General Farman and Rear-Admiral Sharif were with General Niazi when he received the note at about 9 a.m. Farman, who still stuck to the message for ‘cease-fire negotiations,’ said, ‘Is he (Nagra) the negotiating team?’ General Niazi did not comment. The obvious question was whether he was to be received or resisted. He was already on the threshold of Dacca.

Major-General Farman asked General Niazi, ‘Have you any reserves?’ Niazi again said nothing. Rear-Admiral Sharif, translating it in Punjabi, said: ‘Kuj palley hai?’ (Have you anything in the kitty?) Niazi looked to Jamshed, the defender of Dacca, who shook his head sideways to signify ‘nothing.’ ‘If that is the case, then go and do what he (Nagra) asks,’ Farman and Sharif said almost simultaneously.

General Niazi sent Major-General Jamshed to receive Nagra. He asked our troops at Mirpur Bridge to respect the cease-fire and allow Nagra a peaceful passage. The Indian General entered Dacca with a handful of soldiers and a lot of pride. That was the virtual fall of Dacca. It fell quietly like a heart patient. Neither were its limbs chopped nor its body hacked. It just ceased to exist as an independent city. Stories about the fall of Singapore, Paris or Berlin were not repeated here.

Meanwhile, Tactical Headquarters of Eastern Command was wound up. All operational maps were removed. The main headquarters were dusted to receive the Indians because, as Brigadier Baqar said, ‘It is better furnished.’ The adjoining officers’ mess was warned in advance to prepare additional food for the ‘guests.’ Baqar was very good at administration.

Slightly after midday, Brigadier Baqar went to the airport to receive his Indian counterpart, Major-General Jacob. Meanwhile, Niazi entertained Nagra with his jokes. I apologize for not recording them here but none of them is printable! Major-General Jacob brought the ‘surrender deed,’ which General Niazi and his Chief of Staff preferred to call the ‘draft cease-fire agreement.’ Jacob handed over the papers to Baqar, who placed them before Major-General Farman. General Farman objected to the clause pertaining to the ‘Joint Command of India and Bangladesh.’ Jacob said, ‘But this is how it has come from Delhi.’ Colonel Khera of Indian military intelligence, who was standing on the side, added, ‘Oh, that is an internal matter between India and Bangladesh. You are surrendering to the Indian Army only.’ The document was passed on to Niazi, who glanced through it without any comment and pushed it back across the table to Farman. Farman said, ‘It is for the Commander to accept or reject it.’ Niazi said nothing. This was taken to imply his acceptance.

In the early afternoon, General Niazi drove to Dacca airport to receive Lieutenant-General Jagjit Singh Aurora, Commander of Indian Eastern Command. He arrived with his wife by helicopter. A sizeable crowd of Bengalis rushed forward to garland their ‘liberator’ and his wife. Niazi gave him a military salute and shook hands. It was a touching sight. The victor and the vanquished stood in full view of the Bengalis, who made no secret of their extreme sentiments of love and hatred for Aurora and Niazi respectively.

Amidst shouts and slogans, they drove to Ramna Race Course (Suhrawardy Ground) where the stage was set for the surrender ceremony. The vast ground bubbled with emotional Bengali crowds. They were all keen to witness the public humiliation of a West Pakistani General. The occasion was also to formalize the birth of Bangladesh.

A small contingent of the Pakistan Army was arrayed to present a guard of honour to the victor, while a detachment of Indian soldiers guarded the vanquished. The surrender deed was signed by Lieutenant-General Aurora and Lieutenant-General Niazi in full view of nearly one million Bengalis and scores of foreign media men. Then they both stood up. General Niazi took out his revolver and handed it over to Aurora to mark the capitulation of Dacca. With that, he handed over East Pakistan.”

Source: Siddiq Salik, Witness to Surrender (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1977), 208–11.