Historical Context

Pakistan was created in 1947 as a homeland for Muslims of the Indian subcontinent, comprising two geographically separated wings: West Pakistan (present-day Pakistan) and East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh), separated by over 1,000 miles of Indian territory. Despite East Pakistan having a larger population (approximately 56% of Pakistan’s total population), political and economic power was disproportionately concentrated in West Pakistan. This disparity fueled resentment in East Pakistan, where Bengalis felt marginalized in terms of representation, resource allocation, and cultural recognition.

From 1947 to 1970, Pakistan experienced political instability, including the imposition of martial law in 1958 under General Ayub Khan. Ayub’s regime introduced the Basic Democracies system, which limited direct democratic participation. By the late 1960s, widespread discontent with military rule, economic disparities, and regional neglect led to mass protests across Pakistan. In East Pakistan, the grievances were particularly acute, crystallized in the Awami League’s Six-Point Program, which demanded greater autonomy for the provinces.

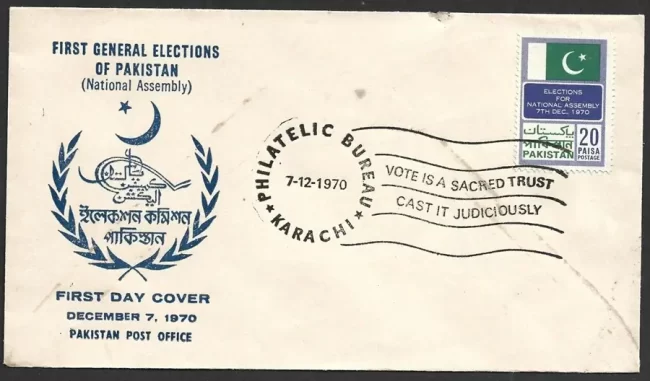

In 1969, under pressure from nationwide protests, Ayub Khan resigned, and General Yahya Khan assumed power. Yahya promised to restore democracy and announced general elections for 1970, based on universal adult franchise, to elect a National Assembly tasked with drafting a new constitution. In mid-1969, Yahya Khan and his advisors had anticipated that no single party would secure an outright majority in the National Assembly. They expected a fragmented outcome, leading to a coalition government that Yahya could manipulate from above. Yahya announced the Legal Framework Order (LFO) of 1970 on March 30, 1970 outlining the election process, allocating seats based on population: East Pakistan received 162 seats, and West Pakistan received 138 seats out of a total of 300 general seats in the National Assembly.

Electoral Framework and Campaign

The 1970 election was conducted under a first-past-the-post system, with direct voting for the National Assembly and provincial assemblies. The LFO stipulated that the new constitution required approval within 120 days of the assembly’s first session, failing which the assembly would be dissolved. Political parties were allowed to campaign freely, a significant departure from the restricted political environment under Ayub Khan.

In East Pakistan, the Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, emerged as the dominant political force. The party’s Six-Point Program, introduced in 1966, was the cornerstone of its campaign. The program demanded a federal structure with substantial provincial autonomy, including control over taxation, trade, and foreign exchange, leaving only defense and foreign affairs to the central government. This resonated deeply with East Pakistanis, who felt economically exploited and politically sidelined by West Pakistan. The Awami League’s slogan, “Joi Bangla” (Victory to Bengal), galvanized Bengali nationalism.

However, Sheikh Mujib’s campaign was not perceived well even by West Pakistani moderates such as Asghar Khan, a former Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Air Force and a senior politician who led the Tehrik-i-Istiklal party. He wrote in his book Generals in Politics: Pakistan 1958–1982 (UPL, Dhaka, 1983: 22–23):

In this pre-election period, Yahya Khan maintained liaison with Mujib-ur-Rehman and appeared to be satisfied with his bonafides. He did not expect the Awami League to win the sweeping victory that it did and he was confident that he would be able to manage things as artfully after the elections, as he had done in his first year in power. Yahya Khan, therefore, was willing to overlook the extreme stand of the Awami League in its election campaign, although it amounted to the violation of his own Legal Framework Order. The election campaign which ran for about a year was probably the longest of any, in contemporary history and gave Mujib-ur-Rehman ample time to build up the strength of his party and convince the people of East Pakistan of the injustices to which they had been subjected.

The elections announced for October 1970 had to be postponed because of floods in East Pakistan in August, which created great havoc and suffering. These floods were followed by a tidal wave of great intensity in November. By then, the campaign of hate against West Pakistan had been so effectively launched by the Awami League that the inability of the government to ameliorate the suffering of the people further charged the political atmosphere to the Awami League’s advantage. The elections in December,therefore, produced a result that few had anticipated.

In West Pakistan, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), led by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, gained traction with its socialist agenda, promising “Roti, Kapra, aur Makan” (Bread, Clothing, and Shelter). Other parties, including the Muslim League factions, Jamaat-e-Islami, and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, also competed but lacked the broad appeal of the Awami League or PPP in their respective regions.

The campaign in East Pakistan was marked by intense mobilization. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s charismatic leadership and the Awami League’s focus on regional grievances, such as the lack of cyclone relief after the devastating Bhola Cyclone in November 1970, amplified its support. The cyclone, which killed an estimated 300,000–500,000 people in East Pakistan, highlighted the central government’s inadequate response, further alienating Bengalis and boosting the Awami League’s campaign.

Election Results

Election day was declared a public holiday. Voter turnout was high, at approximately 63%, reflecting significant public engagement. The total number of registered voters across the two wings of Pakistan was 55.2 million.

The election results were a clear reflection of Pakistan’s regional divide. The Awami League won a landslide victory in East Pakistan, securing 160 of the 162 general seats allocated to the province (plus 7 reserved women’s seats, giving it 167 seats in total). This gave the Awami League an absolute majority in the 313-seat National Assembly (including 13 reserved women’s seats). The party’s dominance was near-total, winning 75% of the popular vote in East Pakistan and capturing every constituency except two, which went to independent candidates.

In West Pakistan, the PPP emerged as the leading party, winning 81 of the 138 general seats, primarily in Punjab and Sindh. Other parties, such as the Muslim League (Qayyum faction) and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, secured smaller shares, but none could rival the PPP’s influence in the west.

The results underscored a stark reality: no major party won significant seats outside its regional stronghold. The Awami League won no seats in West Pakistan, while the PPP secured none in East Pakistan. This polarization set the stage for a political crisis, as the Awami League’s majority entitled it to form the central government and draft the constitution, a prospect that alarmed West Pakistani elites.

East Pakistan’s Role and Dynamics

East Pakistan’s overwhelming support for the Awami League was rooted in decades of grievances. Economically, East Pakistan generated a significant portion of Pakistan’s export revenue, particularly through jute, but received disproportionately low investment in infrastructure, education, and industry. Politically, Bengalis were underrepresented in the military and bureaucracy, and the imposition of Urdu as the national language was seen as an affront to Bengali cultural identity.

The Six-Point Program was a radical demand for restructuring Pakistan’s federal system, effectively proposing a confederation. While it resonated with East Pakistanis, it was viewed with suspicion in West Pakistan, where many saw it as a step toward secession. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s campaign speeches emphasized autonomy within a united Pakistan, but his rhetoric also reflected growing Bengali nationalism, particularly after the Bhola Cyclone exposed the central government’s neglect.

The cyclone, striking just weeks before the election, was a turning point. The central government’s slow and inadequate response—coupled with international aid being routed through West Pakistan—intensified East Pakistani resentment. The Awami League capitalized on this, framing the election as a referendum on Bengali rights and dignity. Mujib’s rallies drew massive crowds, and his message of self-determination struck a chord with a population weary of exploitation.

Post-Election Crisis

The Awami League’s absolute majority should have allowed it to form the government and draft the constitution. However, the results alarmed West Pakistani political and military elites, who feared that the Six-Point Program would dismantle the centralized power structure. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and the PPP, despite their strong showing in West Pakistan, refused to accept a subordinate role in a government led by the Awami League. Bhutto argued that the PPP, as the leading party in West Pakistan, should have a significant say in governance, proposing a “grand coalition” or power-sharing arrangement.

General Yahya Khan, the military ruler, delayed the convening of the National Assembly, citing the need for negotiations between the Awami League and PPP. This delay fueled suspicions in East Pakistan that the military and West Pakistani elites were conspiring to deny the Bengalis their mandate. On March 1, 1971, Yahya indefinitely postponed the assembly session, triggering mass protests in East Pakistan. On March 7, 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman delivered a historic speech in Dhaka, calling for a non-violent struggle for independence while stopping short of declaring secession.

The failure to honor the election results led to a breakdown in negotiations. On March 25, 1971, the Pakistan Army launched Operation Searchlight, a brutal crackdown in East Pakistan aimed at suppressing the Awami League and Bengali nationalism. This marked the beginning of the Bangladesh Liberation War, which culminated in the creation of Bangladesh in December 1971, with India’s military intervention.

Significance and Legacy

The 1970 election was a defining moment in Pakistan’s history, exposing the fragility of its national unity. In East Pakistan, it was a triumph of democratic expression, as Bengalis used the ballot to assert their demand for autonomy and justice. However, the refusal of West Pakistani elites to accept the results revealed the limits of democracy in a deeply divided state.

The election highlighted the failure of Pakistan’s leadership to address regional disparities and foster an inclusive national identity. The Awami League’s landslide victory was not merely a political win but a reflection of East Pakistan’s distinct cultural, linguistic, and political aspirations. The subsequent war and secession of Bangladesh had profound consequences, reducing Pakistan to its western wing and reshaping South Asian geopolitics.

In Bangladesh, the 1970 election is remembered as a milestone in the struggle for independence, symbolizing the power of democratic mobilization. In Pakistan, it serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of ignoring regional grievances and undermining democratic mandates. The election’s legacy continues to influence discussions on federalism, democracy, and national unity in both countries.

Archival Note

The content on this page has been archived and curated by Shamsuddoza Sajen, Chief Archivist of Bangladesh on Record.