ANANTA YUSUF

The forebears of Mohammad Alam and Mohammad Ali, two Rohingya refugees, were Myanmar citizens. They had been in Myanmar for generations.

But Alam and Ali are not rightful citizens of the country. Having white cards, they had voted in the 2010 general elections. But now they have blue cards, under which they have very limited rights.

Escaping violence in Rakhine State, they entered Bangladesh early this month. The two along with their 31 family members have taken refuge at the unregistered Rohingya camp in Taknaf’s Kanjhan Para.

The fate of the ethnic minority changed with the changing of policies by the government. Many legal Myanmar citizens from the Rohingya community became illegal immigrants as the colours of their identity cards changed over the years. The government curtailed some of their basic civil rights.

Talking to us on September 7 2017, Alam said he walked four days to reach Teknuf in Cox’s Bazar from Maungdaw district of Rakhine.

Looking exhausted and distressed, he was reminiscing about his days in Rakhine. “We have proper land records. My grandparents and parents got Myanmar citizenship using their land deeds.”

He has brought those papers with him to Bangladesh. He is hopeful about regaining his land on return to Myanmar someday.

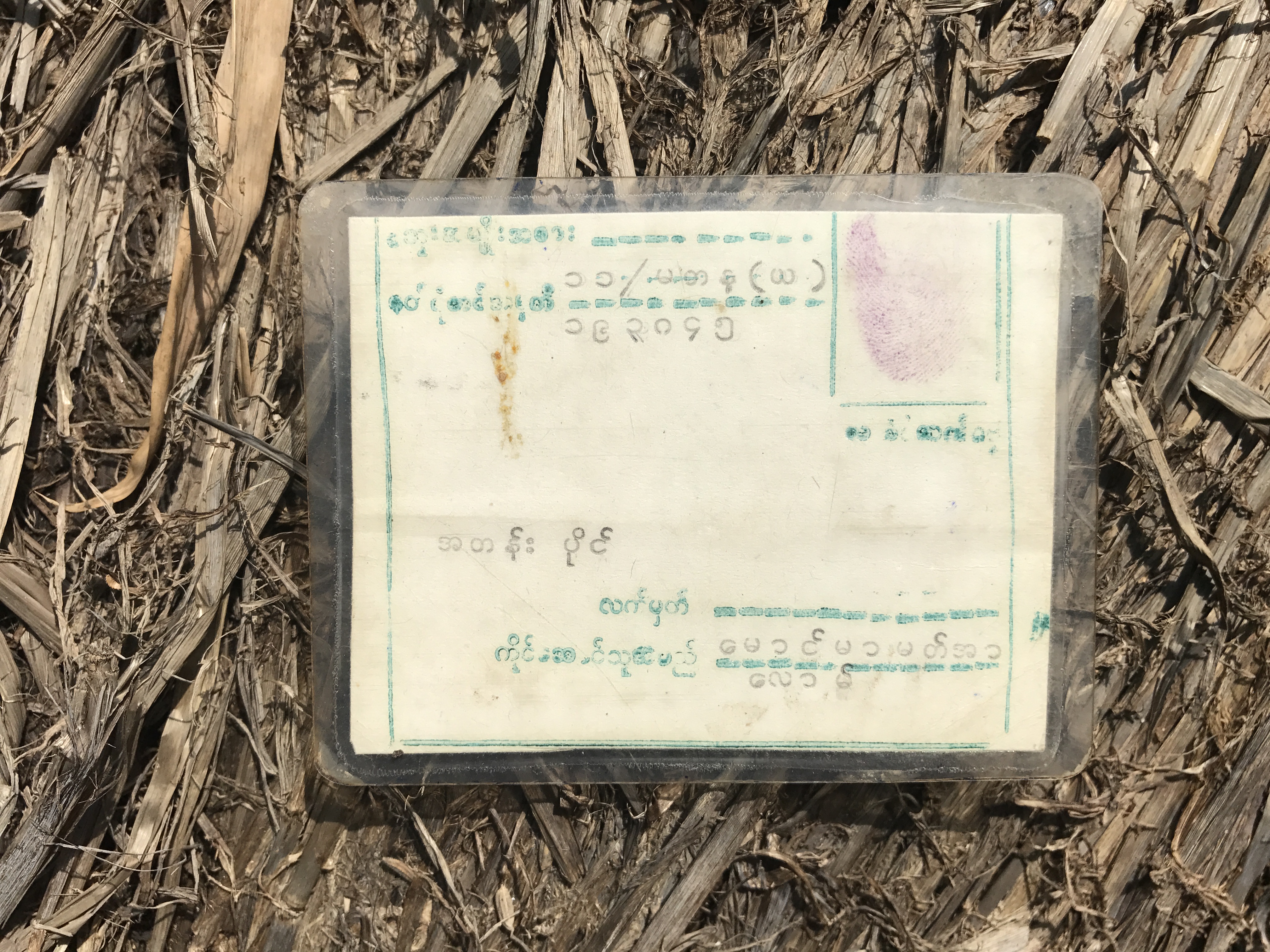

Alam showed some citizenship documents. He was holding tight three cards registered in 1952. These are his precious treasure as he finds a glimpse of hope to become a rightful Myanmar citizen.

In fact, the Myanmar government previously had taken back only those Rohingyas who managed to bring documents with them to Bangladesh.

Refugees like Alam and Ali are still preserving the cards very carefully. The 67-year-old pieces of paper have become brown and somewhat tattered. Each of the documents has the cardholder’s photograph, name, date and place of birth, father’s name and address. All the information is written in Burmese.

At the bottom, there is the date of issuance in English. A fingerprint of the cardholder and the signature of the issuer government official are on the back of the card.

The then Myanmar government introduced a law, Union Citizenship Act 1948, under which members of only eight ethnic minority communities were considered citizens. The Rohingyas were taken off the list of the minority communities.

However, a few Rohingyas, including the forebears of Alam and Ali, got citizenship cards when the government distributed National Registration Cards (NRC) under the law in 1951.

The Myanmar government is now rejecting the NRCs.

Asked why the army was torching villages in Rakhine, Ali, aged about 60, said: “I believe the government inflicted torture on the Rohingyas in an attempt to destroy all the evidence of our citizenship.”

After seizing power in a coup d’état in 1962, military ruler Ne Win started restricting movements of Rohingyas in the country. Before that, holders of NRC could receive good education, health service and other government facilities.

But things changed completely when the Citizenship Act, 1982, came into force. It limited participation of Rohingyas in politics.

Interestingly, according to article 6 of the act, those who had citizenship cards were to be recognised as Myanmar citizens. But the military junta overlooked the legal provision and claimed that Rohingyas were illegal migrants from Bangladesh and trying to get Myanmar citizenship hiding their Bengali identity.

Ali claimed that the government started torturing them after the Citizenship Verification Campaign had began in 1989. “At that time the government didn’t upgrade our cards and even the citizenships of the descendants of lawful citizens were revoked”.

He said his family had submitted all the necessary documents, including land records, but the government ignored those.

A new type of card, Citizenship Scrutiny Card, was distributed instead of the National Registration Cards in 1989 through the so called Citizen Verification Campaign. The Rohingyas were not provided with the new cards. Instead, they were given a white card in 1995, and around 4,00,000 Rohingyas from 13 townships were registered under white cards.

Holders of white cards were merely considered as immigrants. Ali said this card was necessary for availing trade permission, education, healthcare facility and travel within the country. “You can’t even get admitted to a hospital if you don’t have a white card. Many people in our village remained out of the purview of the medical treatment as they had no cards.

“After 1995, government officials used to visit our home every year to take family photographs. The government considered us immigrants though our forebears were Myanmar citizens.”

Another Rohingya refugee Shamsul Alam said a Rohingya without a white card could not even visit a bazar, let alone setting up a business. All the undocumented people have been living in camps in Rakhine.

The Rohingyas even didn’t get permission for getting married. Police would stop them verifying their cards at almost all locations.

“After 1995, many of our women came to Bangladesh to get married with Rohingyas living in camps here to avoid bribing the Myanmar army for marriage. Besides, there were many other hassles,” said Shamsul from Maungdaw, now living in Kutupalong camp of Ukhia.

In 2015, the Myanmar immigration ministry abrogated the white cards and distributed green and blue cards among the Rohingyas. According to the ministry, holders of green cards would be able to apply for citizenship directly. The blue cards had a two-year tenure which could be extended upon expiry.

Not a single Rohingya has a green card in Myanmar. The new cards have curtailed more citizen facilities that they had enjoyed before. The helpless people have to take permission from the government and face a lot of hassles even for securing the most basic needs.

The discriminations against the Rohingya Muslims have been going on for decades. Their miseries have increased in the last three weeks as they are being evicted from their homes and killed, raped and looted.

The Rohingyas are simple people who want to live in peace and with dignity. Having a small shanty now seems to be a far cry for the Rohingyas — the most persecuted ethnic minority community in the world.