War babies are referred to here as babies born to Bangali women consequent of their being raped by Pakistani soldiers and other criminals who took advantage of the situation of the war of liberation (March to December 1971). While they are referred to as the ‘unwanted children’, the ‘enemy children’, the ‘illegitimate children’, and more contemptuously, the ‘bastards’, their birth-mothers are also variously referred to as the ‘violated women’, the women’, the ‘distressed women’, the ‘rape victims’, the ‘victims of military repression’, the ‘affected women’ and the ‘unfortunate’ women. Many birth-mothers committed suicide in order to avoid social stigma. Many pregnant women went to India and other places either to terminate pregnancies or arrange deliveries. Many babies were born at home. But unfortunately, accurate or fairly reliable statistics are not available for any of these categories of victims. The situation has led us to make guesswork and presumptions about the number and fate of war-babies. Some limited evidences are to be found in government and non-government organisations records, and in records of foreign missions and missionary organisations.

An Italian medical survey, for example, put the number of victims at 40,000, the London-based International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) estimated it at 200,000. Dr. Geoffrey Davis, a social worker dealing with the management of war-babies at the time argued that the number could go higher. How many victims got pregnant and delivered babies is absolutely uncertain. A government estimate put it at 300,000. But the methodology adopted for reaching this figure was not sound. According to Dr. Davis, about 200,000 women became pregnant. But it was only his guess, not a study.

Newspaper reports of the time, which included interviews of Justice KM Sobhan, Chairperson, BWRP, Sister Margaret Mary of Missionaries of Charity, Dr. Geoffrey Davis, the IPPF personnel such as Odert von Shoultz, reveal that 23,000 abortions were performed at various Dhaka clinics by a team of British, American and Australian doctors, with assistance from some Bangali counterparts. In a sense, it makes the most comprehensive information on abortion in early 1972, following the arrival of the foreign doctors in Dhaka who set up several abortion/delivery clinics referred to as Seba Sadan in Dhaka.

Newspaper reports indicate that between 300 and 400 children were born in the premises of 22 Seba Sadans’ which were established across Bangladesh. The Executive Director of the Canadian UNICEF Committee, following his visits to both occupied Bangladesh and independent Bangladesh, where he held discussions with representatives of the League of Red Cross Societies and the UNICEF personnel, reported to headquarters in Ottawa that the estimated number of the war-babies was nearly 10,000. While no exact records are available to determine the accuracy of such figures, it is probably safe to assume that the number seems incredibly high. Ten thousand is, by far, the largest number quoted in any record that made reference to the birth of the war-babies in 1972.

Government’s initiatives in tackling the problem: The first, and most important, initiative that the government of Bangladesh took was the creation of a body called Bangladesh Women’s Rehabilitation Board (BWRB) on 18 February 1972. Partnering with the Directorate of Training, Research, Evaluation and Communication (TREC) of the Bangladesh Family Planning Association, the Central Organisation for Women’s Rehabilitation, the Directorate of Social Welfare of the Ministry of Social Welfare and Labour, the Board had two broad goals: (i) to organize clinical services wherever possible in Bangladesh within the limited time span of three to four months to provide medical treatment to the rape victims; and (ii) to plan, organize and establish facilities and institutions, specially vocational training centres, to effectively rehabilitate thousands of destitute women in need of immediate help. Destitute women were not necessarily ‘violated women’ but were considered to be ‘war-affected’ in that they had lost either their husbands or the bread earners of the family (such as father, etc), killed by the Pakistan army, or had lost their property during the war.

Through its Rehabilitation Programme for the Violated Women, the government sought innovative ways to enhance the self-esteem of the victims, and their status in the nation as noble contributors be regarded with pride. Honouring the unsung heroines, the government had declared that they deserved national recognition for their valiant role in the War of Liberation. In an attempt to find and promote a positive voice around these victims, the government, after several rounds of consultation with interest groups, came forward to honour them with the title of Birangana (heroines) not as a sign of disgrace and humiliation but as a symbol of honour and courage. By honouring them as such, it was believed that they would be seen as the symbol and embodiment of everything that is descent, courageous and noble. It was also believed that such recognition of sacrifice would open the doors for the Biranganas who would then be accepted by the society as both triumphant and tragic. Simultaneously, the government continued to seek advice from all quarters to formulate its policy on the abandoned war-babies.

Inter-country adoption of the war-babies: Following a personal request of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the US Branch of the Geneva-based International Social Service (ISS) was the first international non-profit organisation to come forward to advise the government concerning the war-babies. Two local voluntary agencies, the Dhaka-based Bangladesh Central Organisation for Women Rehabilitation and the Family Planning Association, had worked with the ISS throughout the consultation and implementation phases.

Canadian initiative in adopting the war-babies: Canada was one of the first countries in the world which had expressed an interest to adopt the war-babies of Bangladesh. Through personal efforts of Mother Teresa and her colleagues at Missionaries of Charity, and the government of Bangladesh’s Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare, two Canadian organisations got involved in adoptions. They were the Montreal-based Families for Children, a non-profit adoption agency for inter-country adoption, and the Toronto-based Kuan-Yin Foundation (pursuing relief of distressed children in the world), a non-profit adoption agency initiated by a group of enthusiastic Canadians. There were other countries such as the US, the UK, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden and Australia, to name a few. In addition, there were many organisations, such as, the US-based Holt Adoption Program, Inc and Terre des Hommes.

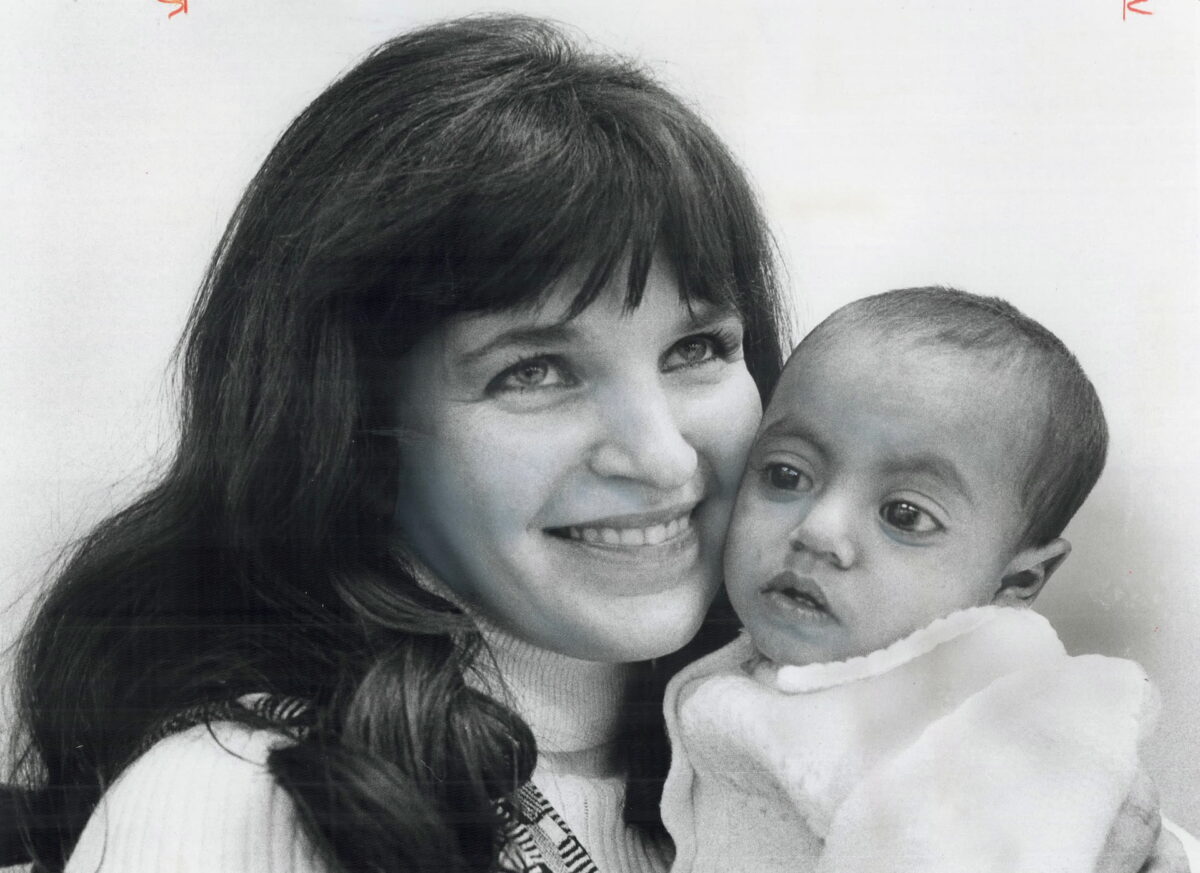

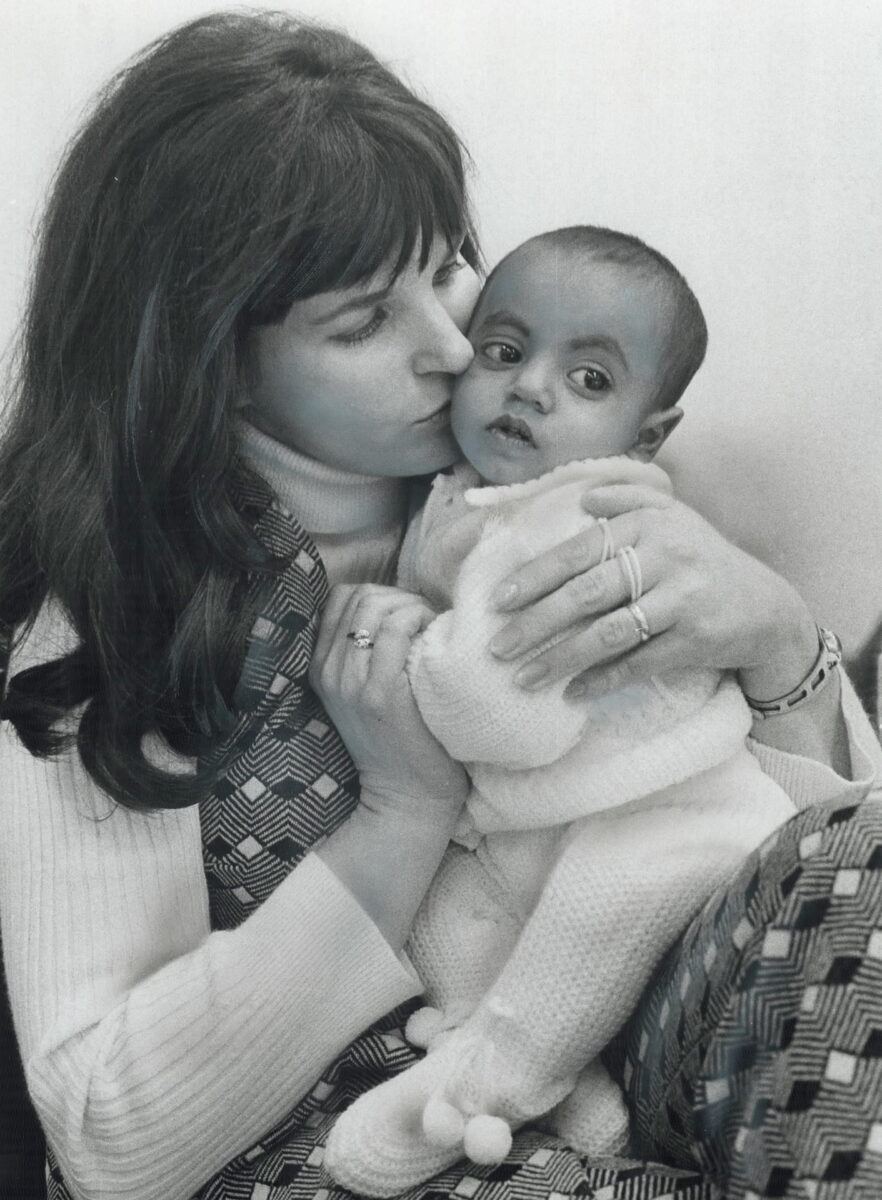

In facilitating adoption of war-babies by foreign nationals, the government promulgated a Presidential Order entitled The Bangladesh Abandoned Children (Special Provisions) Order 1972. When the first contingent of 15 war-babies from Bangladesh arrived in Canada on 19 July 1972, they received comprehensive media coverage for days. The key media message was that interracial adoption programmes were a positive initiative, and that Canadians of diverse background should endorse such an initiative.

The end of the war-baby question: International participation in the re-habilitation of war-babies had a debatable aspect. The adopting agencies of the West showed more interest in the rehabilitation of war-babies, not in their birth-mothers. The war babies were mostly from Muslim women and they were destined to be raised as Christians in the adopting countries, an aspect which made public opinion in Bangladesh quite hostile to inter-country adoption initiative. The war-baby question came to a close by 1974 when the babies were either transported by then to foreign lands as adopted ones or begun to be raised at home as normal domiciles of Bangladesh.

Author: Mustafa Chowdhury

Source: Banglapedia