In West Pakistan, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), led by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, gained traction with its socialist agenda, promising “Roti, Kapra, aur Makan” (Bread, Clothing, and Shelter). Other parties, including the Muslim League factions, Jamaat-e-Islami, and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, also competed but lacked the broad appeal of the Awami League or PPP in their respective regions.

The campaign in East Pakistan was marked by intense mobilization. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s charismatic leadership and the Awami League’s focus on regional grievances, such as the lack of cyclone relief after the devastating Bhola Cyclone in November 1970, amplified its support. The cyclone, which killed an estimated 300,000–500,000 people in East Pakistan, highlighted the central government’s inadequate response, further alienating Bengalis and boosting the Awami League’s campaign.

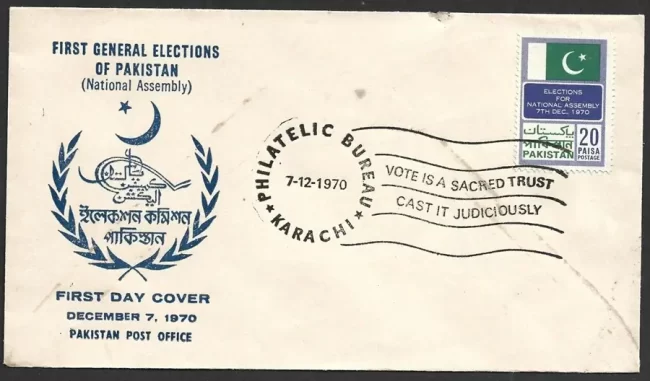

Election Results

Election day was declared a public holiday. Voter turnout was high, at approximately 63%, reflecting significant public engagement. The total number of registered voters across the two wings of Pakistan was 55.2 million.

The election results were a clear reflection of Pakistan’s regional divide. The Awami League won a landslide victory in East Pakistan, securing 160 of the 162 general seats allocated to the province (plus 7 reserved women’s seats, giving it 167 seats in total). This gave the Awami League an absolute majority in the 313-seat National Assembly (including 13 reserved women’s seats). The party’s dominance was near-total, winning 75% of the popular vote in East Pakistan and capturing every constituency except two, which went to independent candidates.

In West Pakistan, the PPP emerged as the leading party, winning 81 of the 138 general seats, primarily in Punjab and Sindh. Other parties, such as the Muslim League (Qayyum faction) and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, secured smaller shares, but none could rival the PPP’s influence in the west.

The results underscored a stark reality: no major party won significant seats outside its regional stronghold. The Awami League won no seats in West Pakistan, while the PPP secured none in East Pakistan. This polarization set the stage for a political crisis, as the Awami League’s majority entitled it to form the central government and draft the constitution, a prospect that alarmed West Pakistani elites.

East Pakistan’s Role and Dynamics

East Pakistan’s overwhelming support for the Awami League was rooted in decades of grievances. Economically, East Pakistan generated a significant portion of Pakistan’s export revenue, particularly through jute, but received disproportionately low investment in infrastructure, education, and industry. Politically, Bengalis were underrepresented in the military and bureaucracy, and the imposition of Urdu as the national language was seen as an affront to Bengali cultural identity.

The Six-Point Program was a radical demand for restructuring Pakistan’s federal system, effectively proposing a confederation. While it resonated with East Pakistanis, it was viewed with suspicion in West Pakistan, where many saw it as a step toward secession. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s campaign speeches emphasized autonomy within a united Pakistan, but his rhetoric also reflected growing Bengali nationalism, particularly after the Bhola Cyclone exposed the central government’s neglect.

The cyclone, striking just weeks before the election, was a turning point. The central government’s slow and inadequate response—coupled with international aid being routed through West Pakistan—intensified East Pakistani resentment. The Awami League capitalized on this, framing the election as a referendum on Bengali rights and dignity. Mujib’s rallies drew massive crowds, and his message of self-determination struck a chord with a population weary of exploitation.

Post-Election Crisis

The Awami League’s absolute majority should have allowed it to form the government and draft the constitution. However, the results alarmed West Pakistani political and military elites, who feared that the Six-Point Program would dismantle the centralized power structure. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and the PPP, despite their strong showing in West Pakistan, refused to accept a subordinate role in a government led by the Awami League. Bhutto argued that the PPP, as the leading party in West Pakistan, should have a significant say in governance, proposing a “grand coalition” or power-sharing arrangement.

General Yahya Khan, the military ruler, delayed the convening of the National Assembly, citing the need for negotiations between the Awami League and PPP. This delay fueled suspicions in East Pakistan that the military and West Pakistani elites were conspiring to deny the Bengalis their mandate. On March 1, 1971, Yahya indefinitely postponed the assembly session, triggering mass protests in East Pakistan. On March 7, 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman delivered a historic speech in Dhaka, calling for a non-violent struggle for independence while stopping short of declaring secession.

The failure to honor the election results led to a breakdown in negotiations. On March 25, 1971, the Pakistan Army launched Operation Searchlight, a brutal crackdown in East Pakistan aimed at suppressing the Awami League and Bengali nationalism. This marked the beginning of the Bangladesh Liberation War, which culminated in the creation of Bangladesh in December 1971, with India’s military intervention.

Significance and Legacy

The 1970 election was a defining moment in Pakistan’s history, exposing the fragility of its national unity. In East Pakistan, it was a triumph of democratic expression, as Bengalis used the ballot to assert their demand for autonomy and justice. However, the refusal of West Pakistani elites to accept the results revealed the limits of democracy in a deeply divided state.

The election highlighted the failure of Pakistan’s leadership to address regional disparities and foster an inclusive national identity. The Awami League’s landslide victory was not merely a political win but a reflection of East Pakistan’s distinct cultural, linguistic, and political aspirations. The subsequent war and secession of Bangladesh had profound consequences, reducing Pakistan to its western wing and reshaping South Asian geopolitics.

In Bangladesh, the 1970 election is remembered as a milestone in the struggle for independence, symbolizing the power of democratic mobilization. In Pakistan, it serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of ignoring regional grievances and undermining democratic mandates. The election’s legacy continues to influence discussions on federalism, democracy, and national unity in both countries.