The early history of Bengali printing | Bangladesh on Record

June 30, 2019

Cite this item : M. Siddiq Khan. “The Early History of Bengali Printing.” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 32, no. 1 (1962): 51–61.https://bangladeshonrecord.com/project/early-history-bengali-printing/

M. Siddiq Khan

Bengali is the language spoken in the old presidency of Bengal, a territory today divided between modern India, the state of Western Bengal with the capital at Calcutta, and East Pakistan with its capital at Dacca. The primary meaning of “Bengali printing” in the title of this article is printing in the Bengali language, although the discussion is naturally concerned with the territory of Bengal.

The following account is concerned with Bengali printing before 1800, concentrating on the period after the Battle of Plassey in 1757 when the British East India Company established its control of the province.

Although some evidence indicates early native attempts to use Chinese xylographic methods of printing in India,[ Vishwa Kosh (“Bengali Encyclopedia”) (Calcutta: B.S. 1311 [1904/5]), XV, 187; Dinesh Chandra Sen, History of Bengali Language and Literature (2d ed.; Calcutta: University of Calcutta, n.d.), p. 849.] the introduction of printing with movable metal types was a product of European colonizers and missionaries. [For a comprehensive account of early printing in India, see A. K. Priolkar, The Printing Press in India: Its Beginnings and Early Development

(Bombay: Marathi Samshodhana Mandala, 1958).] The Jesuits established a press at the Portuguese colony of Goa in 1556 and subsequently printed also at other Portuguese centers. After beginning with works on Christian doctrine in Portuguese, in 1578 the Jesuits at Quilon printed a book in the Tamil language with Tamil characters. Other European centers in India also showed some interest in printing, and some Indians may have even taken it up. According to some records, Bhimjee Parekh with the aid of the British East India Company established a press at

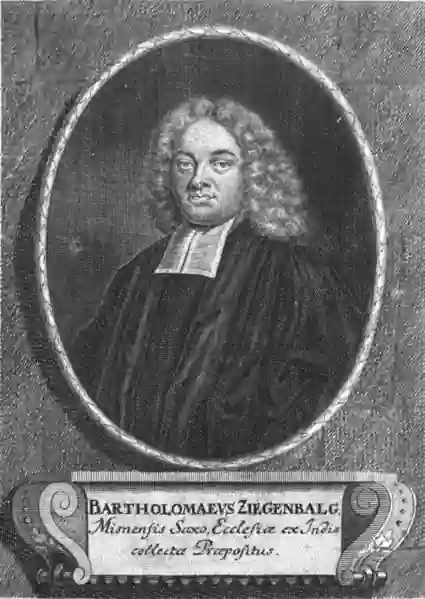

Bombay in 1674-75, but no books survive from it. Bartholomew Ziegenbalg, a Danish missionary [ born in Pulsnitz, Saxony] , established a press at Tranquebar about 1712, which printed with Tamil types. Somewhat later in Rome the Society for the Propagation of the Faith had Sanskrit (Deva Nagari) and Malabar (Tamil and Malayalam) fonts of type cast in 1771 and 1772.

After the Portuguese consolidated their trading and political settlements on the western coast of India, traders and missionaries branched out to other parts of the country. They lost little time in building up a link with Bengal, for its fame as a rich and pleasant land with a large population had spread even in previous centuries from the accounts of Arab and European travelers. Nuno da Cunha, governor from 1529-38, sent an expedition of five vessels to Chittagong (Porto Grande) in 1533. After 1581 a Portuguese trading vessel visited that seaport of Eastern Bengal every year.

Trading colonies and missionary outposts sprang up, including one at Nagori which was associated with the printing of the first three Bengali books.

Several records illustrate the interest of the Portuguese missionaries in Bengali books. On January 3, 1683, Father Marcos Antonio Santucci, the Superior of the Portuguese mission working

among Bengali converts to Christianity, wrote from Nolua Cot to the Provincial of Goa: “The Fathers [Ignatius Gomes, Manoel Surayva, and himself] have not failed in their duty; they have learned the language well, have composed vocabularies, a grammar, a confessionary and prayers; they have translated the Christian Doctrine, etc. nothing of which existed until now.”(3) Francisco Fernandes wrote from Sripur in East Bengal to his Jesuit superior in Goa about his compilation of a booklet expounding the fundamentals of the Christian doctrine and a book of catechisms. His fellow missionary, Dominic de Souza, appears to have translated those two books into Bengali.(4) A little catechism in Bengali by Father Barbier was mentioned as early as 1723.(5)

None of the books mentioned above is extant and it is not known whether or not they were printed. Shortly after them, however, some books were printed in Bengali outside India. The most remarkable of these were three books attributed to Father Manoel de Assumpsao, an Augustinian, who came to Bengal about 1734. As rector of the Mission of St. Nicolas of Tolentino he was attached to the Catholic church at Nagori near Bhowal in the district of Dacca about 1742.(6) He wrote books “for the easier instruction of neophytes.”

A second book by Father Manoel was Compendio dos mysterios da fe, printed at Lisbon by Da Silva in 1743. Bengali on the versos, printed again in roman types, faced Portuguese on

the rectos. This work is also known as the Cathecismo da doutrinaa ordenando por modo de dialogo em idiome bengalle e portuguez. It has become famous by its Bengali title, Crepar Xaxtrer Orth bhed (“The Meaning of the Gospel of Mercy”).

A third book, Vocabulario em idioma bengalla e portuguez dividido em duas partes, was printed by Da Silva at Lisbon in 1743. In two parts, it includes a Bengali-Portuguese and a Portuguese-Bengali vocabulary. A compendium of Bengali grammar precedes the latter.(8) The book is printed entirely in roman types.

Two other Bengali books were composed by Bento de Selvestre (or De Souza), a one-time Catholic missionary who was converted to Protestantism. His translation of parts of the Book of Common Prayer and a catechism were published in London as Prarthanamala and Prasinottarmala. Both were printed in roman types.

This missionary publishing led to little perceptible development of indigenous literature. First, such religious and denominational publishing had little appeal to the general public. Second, the Bengalis of that time lacked the education and the type of social organization necessary to realize the potential benefit of printing on their language and literature. Finally, an atmosphere of futility and negation seemed to affect the Bengali literary climate.

Independent and competent observers like Nathaniel Brassey Halhed (1749-1830) (9) and William Carey (1761-1834) (10), looking for Bengali books in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, recorded an appalling lack of them. Halhed, when compiling his monumental Grammar of the Bengali Language, complained that despite his familiarity with the works of Bengali authors he could trace only six extant books in 1778. These included the great religious epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. All six, of course, were in manuscript. When later the great missionary, William Carey, an eminent scholar of Bengali and Sanskrit, visited Nabadwip, the cultural and religious center of Bengal, he could unearth after arduous search a mere forty handwritten Bengali works.

On this poverty-stricken literary and bibliographic scene, the stage was being set for more extensive Bengali book production. The factors promoting this advancement were mainly political. At

the Battle of Plassey in 1757 the British East India Company gained control of the rich province of Bengal. By 1772, the Company had skillfully employed the sword, diplomacy, and intrigue to take over the rule of Bengal from her people, factious nobles, and weak Nawab. Subsequently, to consolidate its hold on the province, the Company promoted the Bengali language. This did not represent an intrinsic love for Bengali speech and literature. Instead it was aimed at destroying traditional patterns of authority through supplanting the Persian language which had been the official tongue since the days of the great Moguls.(11) Nevertheless, as a result Bengali flourished.

Instrumental in the advancement of Bengali printing was the policy adopted by the Company of teaching Bengali to its employees. Notable English orientalists –Halhed, Carey, and Nathaniel Pitts Forster, for example-stoutly promoted the teaching of Bengali in its pure Sanskritized form. The Islamic languages, including Muslim Bengali, were under attack. The unrelenting efforts of the English champions of pure Bengali, backed by the whole administrative machinery of the East India Company, culminated in the passage of a statute in 1838 whereby the use of Arabic and Persian was prohibited in the law courts established under the jurisdiction of the Company.

Progress in the writing of non-Islamic indigenous languages, however, was rapid. After 1755, public notices in native vernaculars were posted in the Indian bazaars. Warren Hastings, Governor of Bengal in 1772 and Governor-General from 1773 to 1785, showed keen interest in training young English civilians, or “writers,” to do justice to their duties among the Indian subjects of the Company. The learning of Indic languages was an essential requirement and this was emphasized in the curriculum of the Fort William and Haileybury colleges. An active patron of such Indic scholars as Halhed, Wilkins, Gladwin, Jones, and others, Hastings insisted that they produce enough books in the Indic languages for such students.

The objective of encouraging European (and later Indian) scholars to study the Indic languages and to produce books in them was to be even further extended. William Wilberforce, the English philanthropist and politician, proposed in Parliament in 1793, during the governor-generalship of Lord Cornwallis in India, that the East India Company provide more and better facilities for the education of its native subjects. (12) This induced European missionaries and enlightened gentlemen to establish printing presses. Though primarily established for the propagation of the Christian faith and producing a better class of European civilians in India, these presses aimed in part to improve the general educational level. Indirectly at first, they were ultimately instrumental in the development of the Bengali language and literature and in the general spread of education in Bengal.

Two great landmarks in the history of printing in Bengal were the establishment of the Serampore Mission in 1799 and the founding of Fort William College, with the object of “imparting knowledge of the vernaculars to young civilians,” by Lord Wellesley in 1800. In 1816, with the support of the Marquis of Hastings (then governor- general), Butterworth Bailey, William Carey, and others, the Calcutta Book Society was founded.

The first printing press in Bengal was that of a Mr. Andrews at Hooghly in 1778. Halhed’s grammar was printed here. Of this, we know but little more. In 1780, James Augustus Hickey founded the Bengal Gazette Press, publisher of the slanderous Bengal Gazette —known popularly as Hickey’s Gazette. In 1784, Francis Gladwin (13) established the Calcutta Gazette Press, which published the official government gazette and did a good portion of the East India Company’s printing. A little later the government also set up its own printing press with the assistance —and for some time the supervision— of Charles Wilkins, father of Bengali type-founding. Other presses apparently established in the last decades of the eighteenth century were the Calcutta Chronicle Press, the Post Press, Ferris and Company, and Rozario and Company.

A period of censorship and restriction began in 1799. As a wartime measure, the Marquis of Wellesley severely curtailed the freedom of the press by imposing restrictions on printing and publishing at Calcutta and enforcing a cessation of printing outside that city.

This state of affairs continued until 1818 when the Marquis of Hastings restored the freedom of the press. Subsequently a greater number of printing presses were established, including some owned by Indians. By 1825-26, there were about forty presses in Calcutta alone. In addition to the major earlier presses already cited, these included Lavandier’s press at Bow Bazaar, Pearce’s press at Entally, and Ram Mohan Roy’s Unitarian Press on Dhurrumtollah. Baburam’s Sanskrit Yantra at Kidderpore, established at Kidderpore in 1806-7, specialized in the printing of Hindi and Sanskrit books in Deva Nagari types. Other presses were Munshi Hedayetullah’s Mohammadi Press at Mirzapore, the Hindustanee Press, and the College Press.

The first types of the Bengali alphabet, as were those for most other Indian scripts, were cut abroad. The first printed Bengali alphabet appeared in a work of the Jesuit Fathers, Jean de Fontenay, Guy Tachard, Etienne Noel, and Claude de Beze. (14) Bearing the title Observations physiques et mathematiques pour servir a l’histoire naturelle …, it was published at Paris in 1692. A second Bengali alphabet was included in a Latin work written by Georg Jacob Kehr, Aurenk Szeb, printed at Leipzig in 1725. This displayed the Bengali numerals from 1 to 11, as well as the Bengali consonants and a Bengali transliteration of the German name, Sergeant Wolfgang Meyer. These characters were copied by Johann Friedrich Fritz in his Orientalischer und occidentalischer Sprachmeister, printed at Leipzig in 1748.

A Hindustani grammar by Joannes Joshua Ketelaer appeared in Miscellane Oriental, published at Leyden in 1743. This reproduced almost the whole Bengali alphabet, calling it alphabetum grammaticum, including both consonants and vowels. Nothing is known about the casting of these types and they were based on none-too-good models of calligraphy.

In line with English interests in India, English type founders took up the problem of Bengali type. Among the founders engaged in this work was Joseph Jackson. Beginning as a rubber in the Caslon foundry in London, Jack-son rose to the exalted position of cutter of punches, a skill learned on his own initiative in the face of the opposition of the Caslons. Establishing his own foundry, he manufactured various oriental types. An inventory of 1773 listed Hebrew, Persian, and Bengali types in his stock. Bengali was called “modern Sanskrit” and explained as “a corruption of the older characters of the Hindoos, the ancient inhabitants of Bengal.” According to Rowe Mores, Jackson received an order for Bengali type from Willem Bolts, the Dutch adventurer in the East India Company’s service, who was “Judge of the Mayor’s Court of Calcutta.” (15)

As part of their program for popularizing the study of Oriental languages, the East India Company had commissioned Bolts to prepare a grammar of the Bengali language. But although Bolts, who was a man of great enterprise and ingenuity, had represented himself as a great Orientalist, he ran into difficulties with the Company from 1766 to 1768 which culminated in his deportation from India. He was obviously all at sea regarding the cutting of types in the Bengali script. In the words of Reed, “although Bolts was supposed to be in every way competent for the fabrication of this intricate character, his models as copied by Jackson failed to give satisfaction, and the work was for the time abandoned; to be revived and executed some few years later in a more masterly and accurate manner by Charles Wilkins.”(16) Halhed commented about Bolts’s typographical venture as follows: “Mr. Bolts . . . attempted to fabricate a set of type for it with the assistance of the ablest artists in London. But as he egregiously failed in executing even the easiest part, or primary alphabet, of which he has published a specimen, there is no reason to suppose that his project when completed would have been advanced beyond the usual state of imperfection to which new inventions are constantly exposed.”(17) In this failure Jackson seems not to have been at fault so much as Bolts, because Jackson later produced a superior Deva Nagari font under the superintendence of Captain William Kirkpatrick, an officer in the service of the East India Company, for his Grammar and Dictionary of the Hindvi Language.

Mention must be made of The Code of Gentoo Laws translated by Nathaniel Brassey Halhed. Printed in 1777, it contained a plate each of Bengali and Deva Nagari types.(18)

A common failing of these earliest Bengali types was their close adherence to handwritten alphabets produced by scribes. Following such models, the type founders incorporated personal idiosyncracies, unorthodoxies, and inaccuracies. This seems to be a failing of pioneer type-casting in all alphabets. Polk has remarked about the early printers in Europe that they “even assiduously attempted to counterfeit the workmanship of the scribes … in order that their handiwork might actually appear as manuscript.”(19)

The first significant stride in Bengali typography, printing, and publication was made in 1778 with the appearance of A Grammar of the Bengal Language by Halhed. This historic volume was printed in the press of a Mr. Andrews at Hooghly, a small town about fifteen miles from Calcutta. The tremendous typographical achievement was made possible by the strenuous and unremitting pioneer efforts of Charles Wilkins (1749? -1836), who was dubbed the Caxton of Bengal.(20)

At about the age of twenty-one, Wilkins took service as a “writer”(21) in the East India Company and sailed for Bengal. Like other English civilians in India, he diligently studied Sanskrit and Persian. In addition he experimented with the production of types for printing those languages. At this time Warren Hastings was Governor General. Despite his rather checkered career as an administrator, he was a patron of learning—both eastern and western. He had inspired Halhed to compose the treatise on Hindu law and theories of government, published as The Code of Gentoo Law. Encouraged by that success, Halhed had gone on to compile A Grammar of the Bengal Language.

When Halhed had his manuscript ready for printing, he discovered that there was no font of Bengali type available. Jackson’s Bengali font was incomplete and unsatisfactory. In this predicament he turned to Hastings and probably suggested Wilkins, fortunately posted at the Company’s Hooghly factory as a type founder. The result was Wilkins’ Bengali font. “The advice and even the solicitation of the Governor General prevailed upon Mr. Wilkins … to undertake a set of Bengal types. He did and his success has exceeded every satisfaction. In a country so remote from all connection with European artists, he has been obliged to charge himself with all the various occupations of the Metallurgist, the Engraver, the Founder and the Printer.” (22) He surmounted all his obstacles so well, by dint of personal labor, that he was hailed as a man able to bring single-handed perfection to the kind of task which usually requires decades and the collaboration of many men.

In assessing the nature of Wilkins’ achievement, we must realize that, as contrasted to the smaller number of characters in a roman type font, the average Indian script has over six hundred letters, including vowel signs, combinations, etc. Work on such a font is more arduous and time-consuming and requires greater skill. Stocking a composing room is also more costly. According to Norman A. Ellis, “In hand type-setting a double case of Roman characters can do the job for book work, but up to seven cases of a similar size are needed for an Indian script.”(23)

A Grammar of the Bengal Language was a full-sized work using copious extracts from the main Bengali books then extant. Wilkins had to solve most of the problems of Bengali typography to cut types for it. He continued his work in cutting Bengali types at Hooghly until 1786 and later at the Company’s press at Calcutta. This latter press advertised its capacity to print books in Bengali. Examples of Bengali books issuing from this press were Jonathan Duncan’s translation of The Regulations for the Administration of Justice in the Courts of Dewanee Adaulat in 1785 and N. B. Edmonstone’s Bengal Translation of Regulations for the Administration of Justice in the Fouzdarry or Criminal Courts in 1791. Obviously there is more involved here than the technical labor of cutting punches and stamping matrices. The Bengali Encyclopedia, Vishwa Kosh, has called Panchanan Karmakar, the Bengali blacksmith who did the metal

12. J. C. Marshman, The Story of Carey, Marshman & Ward: The Serampore Missionaries (London: J. Heaton, 1864), p. 7.

13. Gladwin’s press was sold at the end of 1786 or early in 1787 to Morris Harrington and Mair.

14. Hosten, op. cit., p. 40.

15. Edward Rowe Mores, A Dissertation upon English Typographical Founders and Founderies (London: privately printed, 1778), p. 83, quoted in Talbot Baines Reed, A History of the Old English Letter Foundries (rev. ed.; London: Faber & Faber, Ltd., 1952), p. 313.

16. Ibid.

17. Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, A Grammar of the Bengal Languages (Hooghly, 1778), pp. iv-xii (Introduction).

18 Das, op, cit,, p. 59.

19. Ralph W. Polk, The Practice of Printing (Peoria: Manual Arts Press, 1937), p. 7.

20. For a concise biographical account of Wilkins, see the Dictionary of National Biography, XXI, 259-60. The date of his birth is given variously in different sources as 1749, 1750, or 1751. In this article, as in the case of the article on Halhed in DNB previously cited, the press at Hooghly is stated to be Halhed’s own, an assertion not supported by any other source.

21. According to Yule and Burnell in Hobson- Jobson “writer” was the rank and style of the junior grade of covenanted civil servants of the East India Company which was abolished from 1833. The term originally described the duty of these young men who were clerks in the factories.

22. Halhed, op. cit.

23. Norman A. Ellis, “Indian Typography,” The Carey Exhibition of Early Printing and Fine Printing (Calcutta: National Library, 1955), pp. 10-11