This short account of the history of Sonargaon is taken from Dr James Wise’s article titled ‘Notes on Sunárgaon, Eastern Bengal’. It was published in the Journal of Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol 1 (1874). James Wise was the civil surgeon of Dhaka in the 1860s. We have added subheadings (without diacritical marks) for smooth reading. – BoR Editor

Early history of Sonargaon

Sunárgáon, or, as the Hindús called it, Subarnagrám , was the capital of a Hindú principality anterior to the invasion of Muhammad Bakhtyár Khiljí, A. D. 1203. At the date of the invasion, Lakshman Sen , of the Vaidya caste, was on the throne. He had made Nadiá his capital . Defeated he fled to the residence of his ancestor Ballál Sen in Bikrampúr, and either from there or Sunárgáoņ he ruled over the eastern districts. The natives of Bikrampúr still point out with pride the square moat of his palace, which is called “ Ballál Bárí.”

The next thing we hear of regarding this part of the country, according to Mr, Taylor [ Topography of Dacca, page 67], is that it was governed by Muhammadan Qázís. One resided at Bikrampúr, a second at Sunárgáon. The only one whose name has survived, is Pír Adam, or, as he is called by the Muhammadans of Dháká, Adam Shahid (1).

Local tradition represents Ballál Sen as ruling at Rámpál, about a mile from where the tomb now is, when Pír A’dam suddenly appeared with an army and caused pieces of cow’s flesh to be thrown into the palace, which so enraged the monarch, that he marched against his enemy and killed him while at prayers on the spot where the masjid now stands.

The Hindú army is further stated to have been totally defeated at Abdullahpúr, a few miles to the west. It would appear that this tale has some foundation of truth. If there were two Ballál Sens, the later one the son of Lakshman Sen, the difficulties connected with this part of the history of Bengal disappears. That shortly after the invasion of Bakhtyár Khilji officers of his (sic) penetrated into and subdued Eastern Bengal is certain; for if we follow Muhammadan historians, we find that in A. D. 1279 Țughril, or, as he styled himself, Sultán Mughísuddín , was Governor of Eastern Bengal, and his seat of government was Sunárgáoņ. At that date he invaded Jájnagar (2) or Tiparah , and having carried off much treasure, he refused to remit any of it to Dihlí [Delhi].

Reign of Balban

The reigning monarch Ghiyásuddin Balban sent an army against his insubordinate deputy. It was defeated. A second [attempt] shared the same fate. The emperor then marched in person against the rebel, and occupied Sunárgáon, having been joined in his advance by Dhinwaj Rái (3), zamíndár of the city, with all his troops. Țughril fled , but was overtaken and slain, [in] A. D. 1282. Having heard of the death of his enemy, Balban returned to Sunárgáon, and put every one of Țúghril’s family and his principal adherents to death. Not content with this barbarity, the historians record that he executed a hundred faqirs with their Qalandar, because they had instigated Țughril’s rebellion, and had accepted from him three mans [maunds] of gold to maintain their society.

Balban, having subdued the district, conferred the ensigns of royalty on his second son Bughrá Khán, or Náçiruddin Mahmúd, and returned to Dihlí, where he soon afterwards died . Bughrá Khán was succeeded in the government of Bengal by his sons , who resided chiefly at Lak’hnautí. About A. D. 1318, Shihábuddín Bughrá Sháh obtained the throne. His reign is believed to have been short. His brother Ghiyásuddin Bahadur deposed him, and assumed the title of Bahadur Shah. The deposed monarch retired to Dihlí, and secured the intervention of Ghiyásuddin Tughluqsháh on his behalf.

In 1323, the emperor in person advanced with an army to Sunárgáoņ. The usurper submitted, and was sent with a rope round his neck to Dilhí . An adopted son of the emperor, Fath Khán , was left in charge of Sunárgáoņ with the title of Bahrám Khán. He is said to have ruled his province “ with much equity and propriety ” for fourteen years. His death, which occurred at Sunárgáoņ, is fixed at A. H. 739 ( A. D. 1338) . From other sources, however, we learn that Bahádur Shah struck coins at Sunárgáon in A. D. 1327, on which he acknowledges himself a vassal of Muhammad Tughluq.

Two years afterwards, the coins bear the impress of his own name. It is conjectured that on the accession of Muhammad Tughluq, A. D. 1325, he reinstated Bahadur Shah in the government of Sunárgáon, and that having rebelled again he was again defeated, and this time put to death. His dead body, Ibn Baţúțah tells us, was flayed, his skin stripped, and in this state circulated in all the provinces of the empire as a warning to other governors. It was probably at this later date that Bahrám Khán was elevated to the government of Sunárgáon.

Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah usurps power

In the following year, Bengal revolted from Muhammad Tughluq. The revolt was headed by. Fakhruddin Mubárak, who had been ‘silahdár’ or armour-bearer, to Bahrám Khán, and who now assumed the title of Sháh . Qadar Khán, Governor of Lak’bnauti, by order of the emperor, advanced towards Sunárgáon and totally defeated Fakhruddín, and took possession of Sunárgáoņ. Fakhruddín, though a fugitive, did not remain idle. He sent emissaries into the city who bribed the soldiers to kill Qadar Khán under the promise of distributing the treasure among them. The soldiers murdered their commander, and Fakhruddin returning put to death the wives and dependents of his rival. From A. D. 1339 to 1349, Mubarak Shah held undisputed rule over Sunárgáoņ. He was succeeded by Ikhtiyáruddin Ghází Shah, of whom nothing is known.

In 1341 , Ibn Baţúțah travelled in Bengal, and visited Sunárgáoņ, but he gives us no description of the city. He narrates that Shaidá, formerly a faqir, having been appointed náib of Sátgáoņ, revolted and fled to Sunár gáoạ . Fakhruddin sent an army to besiege the city; but the inhabitants, afraid for their lives, seized the unfortunate Shaidé, and sent him prisoner to the king who put him to death.

Ghází Shah succumbed to Shamsuddin Ilyás Shah, who struck coins in Sunárgáon from 753 to 758 A. H. (A. D. 1352 to 1356) . It was during his reign that the independence of Bengal was for the first time recognised at Dihlí. On the coins Sunárgáop is designated “ Hazrat i Jalál,” a title afterwards given to Mu’azzamábád [4], which was made the mint city, probably in the reign of Sikandar Shah, son of Shamsuddin. The name of Mu’azzamábád is found on coins from 1358 to 1379 ; but others with the name of Sikandar Sháh, and stamped at Sunárgáon, with the years from 1355 to 1362 marked on them, have been deciphered.

In 1367, Ghiyásuddin, son of the reigning monarch, rebelled and fled to Sunárgáoņ ; there he collected an army and marched against his father. The two armies met at Gowálpárá, near Ja’farganj, in the Dháká district, and nearly opposite the junction of the Ganges and Jabuná. The father was carried off the field mortally wounded. Eighty years ago (5), his tomb was still pointed out in the neighbourhood. Ghiyásuddin, whose title was A’zam Sháh, ascended the throne. He is chiefly famous for his correspondence with the poet Háfiz, whom he tried to induce to come and reside at his court. It is this monarch’s tomb that is still shown at Sunárgáon (vide below and pl . VIII) .

Sunárgáon in the 14th century seems to have been renowned for holy and learned men, and history informs us that Jait Mal ( Jalaluddin ), when he abandoned the Hindú religion, summoned from Sunárgáoņ Shaikh Záhid, to instruct him in the doctrines of Islám and direct him in the management of his kingdom. It was probably about this time that Sunárgáon swarmed with pírs, faqirs, and other religious mendicants, to a greater extent perhaps than any other Indian city. Amidst the ruins and forest of modern Sunárgáoņ natives assert that at least 150 “ gaddís ” of faqirs are distinguishable. Why they should have resorted to this distant city, is difficult to explain.

History of Sonargaon during Mughal rule

In 1582, the khálicah, or exchequer, lands of Bengal were settled by Rájah Todar Mal. The ninth sirkár was Sunárgáoņ. Its boundaries were the Brahmaputra on the west, Silhat on the north, and the then independent principality of Tiparah on the east. It included the present large parganah of Bikrampúr in Dháká, Baldák’hál, Dak’hin Shahbázpúr, Dáaderá, Chandpúr in Tiparah , and Jogdiah in Noákhálí. It is noteworthy that the city of Dháká was included in the seventh sirkár, that of Bázúhá.

In 1586, Mr. Ralph Fitch visited Sunárgáoņ. He is the only English traveller who has left any description of it. He found the country in a very unsettled state. The great city of Sripore (6) at the junction of the Megna and Padda or Kirtumnásá was in rebellion under its chaudharí or chief magistrate against the reigning monarch “ Zibaldim Echebar” ( Jalaluddin Akbar ).

From Sripore Mr. Fitch proceeded to Sunárgáoộ , which was only five leagues distant. “ King Isacan” ( ‘ lsá Khán) then ruled the city. Owing to the incursions of Portuguese and Mag marauders, the seat of the Muhammadan government was transferred from Rájmahall to Dháká in 1608. It is interesting to mark how the name of Sunárgáoņ now disappears from the writings of the early European travellers, and that of Dháká takes its place. It is not named by Linschoten ( 1589) , and Sir T. Roe ( 1615) mentions that the chief cities of Bengal were “ Rajmahall and Dekaka. ” Sir J. Herbert ( 1630) , however, includes Sunárgaon with Bucola, Seriepore, and Chatigam , among “ the rich and well-peopled towns upon the Ganges. ” Mandelsloe ( 1639) writes of “ Rájmahall, Kaka or Daka, Philipatum , and Sati gam .” In the “ Cosmographie” of Peter Heylyn, published in 1657, Sunárgáoņ is placed on an island in the mainstream of the Ganges.

Of the subsequent history of the city little is known, but the following fact I have ascertained. Sayyid Ghulam Muçtafá, the representative of a family which has held “ lákharáj, ” or rent-free, land at Sa’dípúr close to Sunárgáoạ for several centuries , possesses a most interesting document which affords insight into the fate of the city. This document, or mahzarnámah ,’ is a petition from his ancestor to the emperor, soliciting a renewal of the sanad by which the property was held. It is signed by several of the inhabitants of Sunárgáon, and endorsed with the seals of two Qázís of the city. The witnesses testify from their own observation that Sunárgáon was pillaged by the Mags, and that all the papers belonging to the Sa’di púr family were carried off. Unfortunately this petition has no date to it ; but the sanad sent in reply, signed by Shah Jahan, bears the date A. H. 1033 ( A. D. 1623) . As Jahángir was then reigning, his son Sháh Jahán probably signed for his father. This supposition is confirmed by the words “ A’lá Hazrat,” which are used to distinguish the monarch.

From that date until the present, nothing is recorded of Sunárgáoņ. In Major Rennell’s ” Memoir,” published in 1785, he describes the city as having ” dwindled to a village.” In 1809, Dr. Buchanan came to this part of the country with the intention of visiting Sunárgáon. The parganah (7) he found was called Sunárgáon ; but he was told that its proper name was Udhabganj (8). He was also informed that Subarnagrám , or Sunárgáon, had been swept entirely away by the Brahmaputra, and had been situated a little south from where the custom house of Kálágáchhí now stands. This information was very incorrect. The city that tradition places south of Kálágáchhi was Srípúr, and is nearly fifteen miles south -west of Sunargáoņ. Sunárgáon is often mentioned by Muhammadan historians ; but Mr. Blochmann informs me that it is not described by any of them. By Ibn Baţúțah it is designated as “ impregnable,” or, as the word may be also rendered, “inaccessible.” On his arrival at Sunárgáon, Ibn Baţúțah found a junk preparing to sail for Java, which proves that even in the 14th century it must have been a mart of some importance.

It is to Mr. Ralph Fitch , “ Merchant of London , ” that we are indebted for the only extant account of the city. He writes: “ Sunárgáoņ is a town five leagues from Sripore, where there is the best and finest cloth made of cotton that is in all India. The chief king of all these countries is called Isacan , and he is chief of all the other kings, and he is a great friend to all Christians. The houses here, as they lie in most part of India, are very little, and covered with straw, and have a few mats round about the walls and the door, to keep out the tigers and the foxes ; many of the people are very rich . Here they will eat no flesh , nor kill no beast ; they live on rice, milk , and fruits. They go with a little cloth before them , and all the rest of their body is naked. Great store of cotton cloth goeth from hence, and much rice, wherewith they serve all India, Ceylon, Pegu, Malacca, Sumatra, and many other places.”

About the same period , according to the Ain- i -Akbarí, sirkar Sunár gáon was renowned for the very beautiful cloth called kháçah [khasa], fabricated there, and also for a large reservoir of water in the town of Kayárah Sundar, which gave a peculiar whiteness to the cloth washed in it.

Modern history of Sonargaon

The following account of the old buildings of Sunárgáon was the result of a visit made in January, 1872. It includes a description of all that are known to the residents.

Panch Pir Dargah in Mahallah Baghalpur

It is in a very ruinous state. The wall surrounding the enclosure has fallen down in places, and several large jungle trees grow close to the tombs, and will ultimately destroy them. The sepulchers of these five Pírs are placed parallel to one another, and are raised about four feet from the ground. The river Brahmaputra must in former days have flowed past them. It was at one time intended to cover the tombs with a roof, but the pillars never rose higher than a few feet. The age of those graves, the names of the holy men, and the country whence they came, are unknown to fame; the natives are satisfied by telling that they came from the ‘ pachhim,’ i, e. , west, and they cannot understand why anybody should wish to know more.

At the south west corner of the enclosure is a small uninteresting mosque, which, like the tombs, is rapidly falling into ruin. This dargah is considered so sacred that even Hindús salaam as they pass, and Muhammadan pilgrims resort to it from great distances . There are only two other shrines to which Muhammadans make pilgrimages in Eastern Bengal—one is the tomb of Shah Ali at Mírpúr, a few miles north of Dháká ; the other is the dargah of Pír Badr Auliya [Badr al-Din] at Cháțgáon. The latter is the patron saint of all Hindú and Muhammadan boatmen and fishermen in Eastern Bengal.

Tomb of Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah

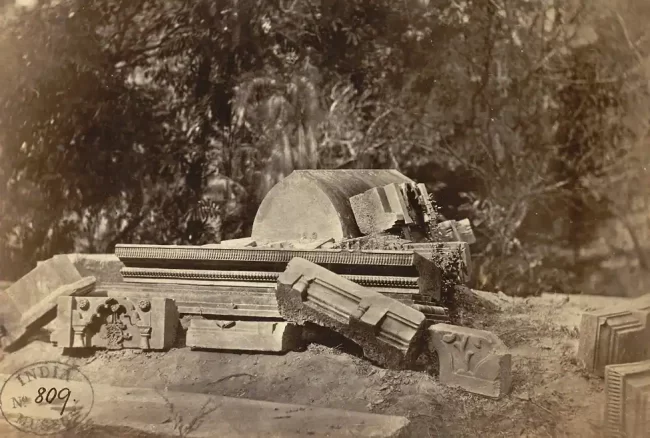

II . About five hundred yards south-east, on the edge of a filthy trench called “ Mag Dighi, ” is the tomb of Ghiyásuddin A’zam Sháh, king of Bengal, and correspondent of the poet Háfiz. This tomb has fallen to pieces. The iron clamps that bound the slabs together have rusted, and the roots of trees have undermined the massive stones. This mausoleum formerly consisted of a ponderous stone which occupied the cen tre, surrounded by pillars about five feet in height. These stones are all beautifully carved, and the corners of the slabs and the arabesque tracery are as perfect as the day they left the workman’s hands. The stones are formed of hard, almost black, basalt . [Vide pl .VIII. (9)]

At the head is a prostrate sandstone pillar half buried in earth. It was apparently used, when erect, as a chirághdán, or stand for a light. This tomb might be easily repaired, and the cost of doing so would be inconsiderable. There is no old building in Eastern Bengal which gives a better idea of Muhammadan taste than this ruined sepulcher; and there is none, when properly repaired, which would so long defy the ravages of time. The Muhammadans of Sunárgáoņ are too poor to reconstruct it themselves. They take great pride in showing it, although they know nothing about it but the name of the Sulțán who is buried there, and they take every care that none of the stones are carried off. Unless Government undertakes the re-erection of this handsome tomb, it is not likely that anything will ever be done.

What increases the surprise of the visitor at seeing this tomb is the contrast between these beautifully carved stones strewing the bank of a filthy hole and the wild luxuriance of the surrounding forest. In close proximity are various tombs, reported to be those of the monarch’s ministers. The roots of trees have destroyed them, and nothing now remains to mark the spot except the brick “pushta,” which preserves the mounds from being washed away.

Magarapara

The village of Magrápárá is considered by the natives of Sunárgáon to be the site of the ancient city. It has in its immediate neighbourhood several undoubtedly old buildings, and within a short distance is an eminence which still bears the name of “ Damdamah,” or fort. This mound, which has a magnificent tamarind tree growing on its top, is circular, but no traces of fortifications are visible. It has been used for many years by the Muhammadans as their “Ashúrkhánah” during the Muharram .

On the tenth day, all the garlands and ornaments that are made in place of ta’ziyahs are here collected and admired by the people. In the small market of Magrapárá is the tomb of Munná Shah Darwish. At the foot, a light is always burned at night. Every orthodox Muhammadan as he passes the tomb stops and mutters a prayer. This saint, about whom nothing is known, is said to have lived at the same time as the more famous Pír whose tomb stands a little to the north . This latter is called the dargáh of Khúndkár Muhammad Yúsuf. It contains the tombs of the saint, of his father, and of his wife. It consists of two elongated dome roofed buildings, each surmounted by two pinnacles covered with or formed of gold.

If any attempt is made to steal the balls, the residents assert that the thief will certainly be struck blind. Some hardened sinner, however, has of late years succeeded in cutting off one; but the believers in this tale cannot tell what his fate was. These tombs are destitute of any ornament inside.

They are kept scrupulously clean, and are covered with sheets, on which devotees throw a few pith-necklaces. When a ryot has reaped an unusually abundant harvest, he, in gratitude, presents a few bundles of ripe rice at the tomb. If any calamity, as the illness of a member of his family, is threatening, he brings rice, or “ batásá,” and prays the saint to avert the affliction .

Hindús are as confident of the efficacy of this propitiatory offering, and as frequently employ it as the Muhammadans. Close to the tombs is a modern Masjid with a “ kitábah ,” or inscription , dated A. H. 1112 (A. D. 1700) . It was probably erected by the Pír Muhammad Yusuf. Facing the mosque is a small graveyard, enclosed by a brickwall. The graves are numerous, but none are of any celebrity. Inserted in the wall at the left-hand side of the entrance is a large, black stone (2 feet by 13) . The natives believe that if a person has lost any property, he has only to put a coating of lime on this stone and he will infallibly get the property back . It was covered with an inch and three quarters of lime at the date it was examined . On scraping off the plaster a beautiful ľughrá inscription was found, with the name Jaláluddín Fath Sháh , A. H. 889 (A. D. 1484). (10)

This is the oldest inscription discovered in the Dháká district, with the exception of the one on A’dam Shahíd’s tomb in Bikrampúr, which bears the same king’s name and the date, A. H. 888. On the roadside near Magrápárá are two other inscribed stones. The writing on both is continuous. It includes the name and title of ’Alá -ud din Husain Sháh, A. H. 919 ( A. D. 1513). (11)

Close to the tomb above mentioned is a ruined gateway called the “ Naubatkhánah,” where musical instruments were sounded morning and evening to announce to travellers and faqirs that a place of shelter was at hand. At the back of the mosque are the ruins of a house called the “ Tahwil,” or treasury, where, within the memory of many living, feasts were given by the superintendent, or mutawallí, of the mosque. The present holder of this post is too poor to entertain anybody. Still further to the north -west are the ruins of the dwellings of the Khúndkárs. It is only within late years that this building, which had an upper room at each end, has become uninhabitable.

The last residents taught boys to recite the Qorán. Now – a -days no education is given in any part of Sunárgáon to Muhammadans. In the Mahallah north of Magrápárá, called Gohațța, is the tomb of a very celebrated Pír, known as Shah ‘ Abdul ‘ Alá , alias Ponkai Díwán. It is narrated that he retired to the forest, where he sat for twelve years so absorbed in his devotions that he was unconscious of the lapse of time. When found, he had to be dug out of the mound the white-ants (popka) had raised around him, and which reached to his neck. The same story is told of Valmiki the sage, and of others. This Pir must have died near the end of the last century, as his son Sháh Imám Bakhsh alias Chulu Miyán came, within the recollection of many living, from Silhaç to die at Sunárgáoņ. Father and son lie buried close together. At the head of the former is placed the lattice-stone on which he spent his memorable twelve years. The tombs are otherwise of no interest. They are merely mud heaps kept carefully clean and covered over with a grass thatch.

In this same quarter, a very large mosque formerly stood which was believed to have been built by the kings. It fell into ruins, and the proprietor sold the bricks to Hindús of Nárayanganj. Muhammadans extenuate this offense by asserting that the proprietor, who was a pensioned deputy magistrate, was insane when he did it. The foundations even are being dug up. The walls had been eight feet thick . The remains of one of the “ mihrábs” still standing, proved that the interior had been ornamented

by carved bricks ; no inscription was to be found.

Yusufganj Masjid

On the roadside east of Magrápárá is a small mosque, called the Yusufganj Masjid. It is rapidly going to pieces, as the dome is covered with masses of pípal trees, whose roots have penetrated into the interior. Its walls are 6 feet 1½ inches thick, which accounts for its standing erect so long.

Pagla Sahib

Beyond the village of Habibpúr, on the right-hand side of the road, is the tomb of “Pagla Sahib,” a very insignificant building. Various stories are told of the reason this Pír received such a singular name. One is that he became “ mast,” or light-headed, from the intensity of his devotions. Another, that he was a great thief-catcher, that he nailed every thief he caught to a wall, and then beheaded him. Having strung several heads together, he threw them into an adjoining “khál,” which has ever since been known as the munda málá, i. e. necklace of heads. This tomb is so venerated that parents, Hindú and Muhammadan, dedicate at the tomb the “chonti,” or queue, of their child when dangerously ill. A little further on the road crosses a nálah by a very fine Muhammadan bridge of great age. It is generally called the Kampaní ke ganj ká pul.

Bari Makhlas

In a quarter near this, called Bári Makhlas, is a comparatively modern mosque, erected by Shaikh Gharibullah, a former jánchandár, or examiner of cloth , to the Company. It bears the date A. H. 1182 ( A. D. 1768), and it is still used by the Muhammadans living in the neighbour hood. Its pinnacles are made of glazed pottery, but the building generally is plain and devoid of interest.

Panam

Painám , although a most singular village, possesses few ancient buildings. There is, however, a fine Muhammadan bridge of three arches, called the Dallálpúr pul, over which the road goes to the Kampaní ká kot’hi. The roadway is very steep. It is formed of bricks arranged in circles of about five feet in diameter. The adjoining bridge leading into Painám village is made in the same way. These circles of bricks are kept in place by several large pillars of basalt laid flat at the toe or rise of the bridges. The old Kampaní ká kot’hi is a quadrangular two-storied , native, brick building,with an arcaded courtyard inside. It was a hired house, and is now occupied by Hindú karmakars, or smiths. In the one street of Painám is a modern and very ugly temple of Shiva, ornamented with numerous pinnacles.

In Amínpúr the ruins of the abode of the royal krori, or tax-gatherer, is shown. Like all old ruins, it is said to contain fabulous treasures protected by most venomous snakes. A descendant of this family still resides in the neighbourhood. Close to his residence are the ruins of an old Hindú building, the only one existing in Sunárgáoņ. It is called “ jhikoti, ” a term applied to a building with an elongated dome roof formed of concrete, and with the walls pierced with numerous openings. It was formerly used for religious purposes.

Goaldia Mosque and Abdul Hamid Mosque

In the division called Goaldih, which consists of dense and impenetrable jungle traversed by a few foot-paths , are two mosques. The first is called ‘ Abdul Hamid’s Masjid . It is in good preservation, being a comparatively modern structure . Its “ kitábah” bears the date A. H. 1116, (A. D. 1705) .

About a hundred yards to the south is the oldest mosque in Sunárgáon. The residents call it the puráná, or old, Goaldih mosque. Its kitábah had fallen out, but had been carefully preserved in the interior. On this stone is inscribed the name of ’ Ala-uddin Husain Shah, A. H. 925 ( A. D. 1519) (12). This curious old mosque is fast going to ruin; pipal trees are growing luxuriantly on the dome, which is cracked, and will soon fall in, and creepers are clinging to the outside walls and aiding in the destruction. It is built of red brick. Its exterior was formerly ornamented by finely carved bricks in imitation of flowers, but neglect and the lapse of centuries has left few uninjured. The interior is 164 feet square. The square walls, as they ascend, become transformed into an octagon. At each corner are quarter domes or arches, and from the intermediate space or “ pendentive ” the dome rises. As usual there are three “ mihrábs.” The centre one is formed of dark basaltic stones, beautifully carved and ornamented with arabesque work. The two side ones are of brick, boldly cut and gracefully arranged. The bricks in the archways have been ground smooth by manual labour, and have not been moulded. The pillars at the doorways are sandstone, evidently the plunder of some Hindú shrine. Until twenty years ago this mosque was used for worship. The khádim , or servant, having died, no care was taken of the building, and the dome threatened to fall in, so worshippers migrated to the modern mosque.

As they do at all the old buildings in Sunárgáoŋ, Hindús salaam as they pass this Masjid.

Sultan Nasiruddin Nusrat Shah’s inscription

Beneath a “gúlar,” or wild fig tree, near Sa’dípúr is a mound with a large stone inscribed in Țughrá characters. Where it came from , or to what it belonged, no one knew. In the inscription the name of Sultán Násiruddin Nusrat Shah, A. H. 929 (A. D. 1523) , is written(13). This stone was carefully removed and deposited in a place of safety at Sa’dípúr.

Khasnagar tank

The only other memorial of former days worth mentioning is the large Kháçnagar tank, south of Painám . It covers 94 acres. of this reservoir is unknown. A few bricks on the west side are evidently the remains of a ghát. This tank has been gradually silting up, and in the month of April there is only six feet of water in it . In former days its banks were covered with the huts of weavers, who found that its water made their muslins remarkably white. The weavers have died out ; but the dhobis who wash clothes in the tank now, assert that the purifying quality of the water surpasses that of any other tank or well. Regarding the site of the old fort of Sunárgáon the residents can give little information . They state that a fort and a mosque, with its dome made of lac, formerly stood on the east of the modern village of Baid Bázár, where the Megná now flows. This is the most likely place for it to have stood, as it would have protected the city from the incursions of piratical ships coming up the river on the east.

Changing course of Brahmaputra and the history of Sonargaon

Any account of Sunárgáon would be imperfect that did not mention the changes in the course of the Brahmaputra, which must have had a most important influence in the selection of the site and on its prosperity. It is a curious fact that the Kalika Puráná poetically relates, that when Balaram cut though the Himalayas with his axe to allow a passage for the pent up waters of the Brahmakund, the goddesses Lakhya and Jabuná both sought to marry the youthful Brahmaputra. The god made choice of the former, and their streams were blended into one. Within the last century, however, the waters of the Lakhya have been gradually drying up, while the main stream of the great river has joined with that of the Jabuná.

In the neighbourhood of Sunárgíon are two places connected in story with the earliest Hindú epics. Nangalband, i. e. , the place where the plough stopped, is the spot where Balaram checked his plough when he undertook to plough the Brahmaputra from its source. Near this is Panchomi Ghát, where the five Pándú brothers, while in their twelve years’ exile, are traditionally said to have bathed. At both of these places thousands of Hindús annually resort to bathe, when the moon of the month of Chait is in a certain lunar mansion. These ancient legends appear to point to a period when the cultivated land terminated at Nangalband. The red laterite soil, which extends from the Gáro Hills through the Bhowal jungles, crops up here and there in the northern parganahs. In Sunárgáon, however, no traces of it are visible. That the alluvium washed down from the hills should first of all be deposited at the termination of this hard formation is most probable, and it was perhaps on this account, as well as on the inaccessibility of the place itself, that the Hindú princes expelled from Central Bengal were induced to found a city here.

In the distribution of the sirkárs of Bengal by Rájah Todar Mall, the Brahmaputra (14) is said to have bounded Sunárgáon on the west . It does so at the present day ; but the stream that bears that name is a shallow one. On the north- west of Sunárgáon, however, the dry bed of a river, which at one time must have been three or four miles broad, is still distinct.

The Mínákháli river, which now – a -days connects the Megná and Brahmaputra, was probably the course that the former took at some early date on its way to join the Lakhya opposite Nárayanganj. This supposition is supported by the fact that when Islám Khán built forts to prevent the Mag marauders from passing up the rivers, the site of one was Hájíganj ; of a second, “ Trivení,” the confluence of three streams, (which could only be the Megná, Brahmaputra, and Lakhya ) ; and of a third, Munshiganj ; that this was the course of the Brahmaputra in former days seems certain. The old bed of the Brahmaputra still exists at Munshiganj, and on its banks is held the time- honoured fair of the Baruní, or Varuní, in the month of Kártik. The spot where this religious festival is held in honour of “ the god of water,” is where the Brahmaputra and the Burhíganga meet.

The Burhígangá, or Dháká River, was the old bed of the Ganges, when it flowed through the great swamps still existing between Nátor and Ja’farganj. Old Sunárgáon would in this case be favourably situated , being protected from the incursions of the hated Muhammadans by the Ganges and Brahmaputra on the west, and from the inroads of the savage hill tribes by the Megná on the east.

In Rennell’s maps, published in 1785, the main stream of the Brahmaputra joins the Megná at Bhairab Bázár, as a small branch does at the present day. Seventy years ago, this was, I understand, the route followed in the hot season by all boats going to and from Asám and Calcutta, and it is not two generations since the Balesar k’hál, which runs through Sunárgáon, was navigable all the [season].

Ruin of Sonargaon

Although it is impossible to fix the date of any of these changes, yet there is every probability that in the days when Sunárgáoņ was a royal city , its walls were washed by one or other of these great rivers . A visit to the jungle of Sunargaon, intersected as it is by trenches of stagnant water and obstructed by raised mounds, suggests the idea that formerly the abodes of the people were elevated above the highest tides, and that the city was traversed by numerous canals and natural creeks. No situation could have been better adapted for a conquered people, whose safety lay in the rivers by which they were surrounded and in the boats which they possessed.

The site of the ancient Sunárgáon is covered by dense vegetation , through which a few winding footpaths pass. The inhabitants are few . The children are all sickly and suffering from spleen disease. The men are generally puny, and so apathetic, that they have not the energy to cut down the jungle, in the midst of which their houses are buried. In the rains all locomotion is by boat. The stagnant holes and swamps of the cold season are then practicable, and the small native boats are punted throughout the jungle between the artificial mounds. In the cold season , these holes contain the most offensive water, laden with decaying vegetable matter. On the banks the largest alligators are seen basking contentedly . The trees are chiefly mangoes, the remains of former prosperity. One decayed stump at Sa’dipúr is still shown as the identical tree of which the unfortunate Shah Shujá’ ate while he halted at Sunárgáoņ.

This variety is still called “ Shujá-pasand.” Throughout the jungle wild guava , bel, almond, and beș trees are found. It is told by the residents with pride – as if the fact reflected honour on Sunárgáoņ — that one “ khirní” tree (Mimu sops Kauki) grows there, while in Dháká only two specimens exist . The ” guláb jáman ” that grows here is reputed to be of unusual delicacy .

Sunárgáoņ pán is celebrated . It is known as “ káfúrí,” from the aroma it gives off when chewed , and is sold at the price of two bírás (96 leaves) a rupee, while the next quality, “sachí,” sells at six paisá , and the “sádah” at four to five paisá . The “mung dál” is also highly esteemed, and it surpasses in quality that grown in any other part of Eastern Bengal. “Sáțhí bhaja,” or fried cream , is not prepared in any other place of this district, although it is , I believe, a common article of diet in Patna. The method of preparing it is only known to the manufacturers. A celebrated kind of dahí, or curd, is also made here. It is known as that of “ Hari Dás Khání.” It sells for four times the price of the country dahi.

Muslin and the history of Sonargaon

The manufacture of the fine muslins, for which Sunárgáon was famous in former days, is now all but extinct. English thread is solely used by the weavers, and the famous “ phúți kapás” is never cultivated. In the Baqirganj [Bakerganj] district, I believe, a little is still grown , but it is only used in making Brahmanical threads, for which English cotton is inadmissible. The only muslin now manufactured by the Hindú and Muhammadan weavers at Sunárgáon is “malmal.” Jámadání, or embroidered cloth, is no longer worked at Sunárgáoņ, although it is at Dhámrái, Uttar Shahpúr, and Qadam -Rasul, in the neighbourhood. The art of weaving the still finer muslins, such as “ tan-zíb ,” “shabnam ,” and ” áb-rawán ,” is unknown at the present day.

The decay of the cotton manufactures of Sunárgáon dated from the end of last century , when the Company ceased to purchase muslins. Before this change, as much as a lákh of rupees was annually distributed from the factory of Sunárgáon to the weavers, and it is estimated that there were then 1,400 families of Hindú and Muhammadan weavers in and around Dallálpúr. In the whole of Sunárgáon it is said that not more than fifty looms are now at work.

Another cause of the falling off in the manufacture of the finest muslins was the stoppage of the annual investment, called “ malbús i kháç.”

The zanánah of the Dihli emperors was supplied with these delicate cloths of Sunárgáoņ and Dháká ; and in Aurangzib’s reign a lákh and thirty thousand rupees were yearly expended under this head.

The unhealthiness of Sunárgáon has been another cause of the decline of the cotton trade, but the most influential of all has been the introduction of cheap English thread, which can be woven into cloth at a much lower price than the native can .

A great trade in cotton cloth, chiefly English piece-goods, is carried on at Panam. The majority of the residents are prosperous merchants, who make extensive purchases in Calcutta and Dháká, which are disposed of in the villages around.

The separation at the present day of the Muhammadan and Hindú population of Sunárgáoņ is unusual. In all the mahallahs to the north and west of Magrápáſá, nine-tenths of the villagers are Muhammadans, while in those to the east the Hindú greatly preponderate. In Painam again there is not a single Muhammadan .

The householders are chiefly ta’luqahdárs, who pay the Government revenue direct to the Dháká treasury. There are ninety of them in this village . There is also a superfluity of Brahmans. In Painam the castes are as follows—thirty houses of Brahmans, sixty – five of Saos, five of Bhúimális, and the remainder of Barbers, &c. At Amíupúr there is a Government school where the children of these families receive education.

Conclusion

The Muhammadans of Sunárgáoņ are contented to remain uneducated ; very few can even read the Qorán, and they have consequently all become Farázís. There are no pírs or faqirs resident at Sunárgáoņ now. The superintendent of the mosque at Magrápárá is a native of Medinipur, who has not as yet acquired the respect of the people. The one man to whom every one resorts for advice and help, and who is regarded as the most holy pír in Eastern Bengal, is Shah Karím ’Alí . He was born in Silhat, and his residence for many years has been Jagannathpúr in the Tiparah district. He is popularly believed to have the power of raising from the dead, and of causing rain to fall at his pleasure.

Sunárgáon is too poor to support saints now, so the saints have migrated to places where the alms of the rich will furnish them with the luxuries which in this degenerate age they find to be necessary.

The Muhammadan women of Sunárgáon are all ” pardah-nishín .” With the changes in the course of the rivers they have been put to much inconvenience and expense. They are no longer able to visit their friends by stepping into a boat and being rowed to the house. They have either to stay at home, or make the trip in a pálkí. There are several families in Sunárgáoņ who claim to be descendants of the old Qázís, but there are none who call themselves Mughuls. Only one man, who is still looked up to as the descendant of an official of the days when Sunárgaon was a royal city, has the unmistakable colour and features of the high -born Tátár race.

Notes

- His tomb at a village called Qází-qaçbáh, south of Riqábí Bázár in Bikrampúr. It was surrounded by a wall and put in thorough repair about a hundred years ago. For centuries a lamp was placed every night on his grave; but the greater enlightenment of the present day, under Farází instruction, has put a stop to such profane rites. Adjoining is a six-domed masjid, with beautiful carved stone and brick-work in the interior. The inscription bears the name of Jalaluddin Fath Shah, and the date is A. H. 888 ( 1483; vide J. A. S. B. for 1873, p. 286.

- The modern tradition in Tiparah is that the old name of the district was Jaháznagar, or the “ city of ships.” This is evidently founded on the circumstance that, at a

much later period, the revenue for the support of the nawárá, or imperial fleet, was derived from lands in this district. - This is probably the same person as Dhinaj Madhub, who is believed to have been a grandson of Ballál Sen.

- About twelve miles north-west of Sunárgáoņ, on the opposite bank of the Brahmapatra, is an old village, which gave its name to one of the parganahs of Sirkár Sunárgáon, called Mu’azzampúr, which Mr. Blochmann identifies with Muʼzzamábád. The only old building there now is the Dargáh of Shah Langar. It attracts Muhammadan pilgrims from long distances, who make offerings on a stone which is believed to bear the holy man’s footprint.

- The tomb of this monarch is, I believe, still shown in the famous Adínah mosque at Panduah, built by him. The tradition, however, in this District is that he was buried where he fell. On the west of Ja’farganj, where the Jabuna flows at the present time, stood a village called Goáriah, where a Dargáh of Sikandar Shah, and a langarkhánah, or hospital, erected by Jahángir, are said to have been. The “oldest inhabitant” is positive, however, that this dargáh was that of a faqír, and not that of a king .

- Near Rájábáſí, where these two great rivers meet, an island called Srípúr has always existed. There is still a tradition that it was formerly a place of great trade. At the present day, this island has joined on to the main land and is called Srípúr Tek, i . e. , Srípúr Point. There was formerly a custom -house here, where sáyir, or transit duties were collected by the government.

- Montgomery Martin’s Eastern Bengal, vol. III. , page 43.

- Udhabganj is a village, about a mile east of Sunárgáon on the Mínákhálí River.

- The lithograph was made from a photograph taken by Mr. W. Brennand, Principal of the Dháká College.

- Vide J. A. S. B., 1873, Part I , p. 285 .

- Vide J. A. S. B., 1872, Part I , p. 333.

- Vide J. A. S. B., 1873, Part I , p. 295.

- Vide J. A. S. B., 1872, p. 338.

- Ibn Bațuțá calls the Brahmaputra Al-nahr ulazraq, “ the blue river”.

1 Comment

Karl

May 10, 2023Your blog is an excellent resource for anyone searching for useful information. Keep up the good work.