In the thick of World War II, while battles raged across Europe and the Pacific, an urgent note from British India’s colonial bureaucracy was quietly setting into motion a military transformation in a coastal city far from the global spotlight—Chittagong.

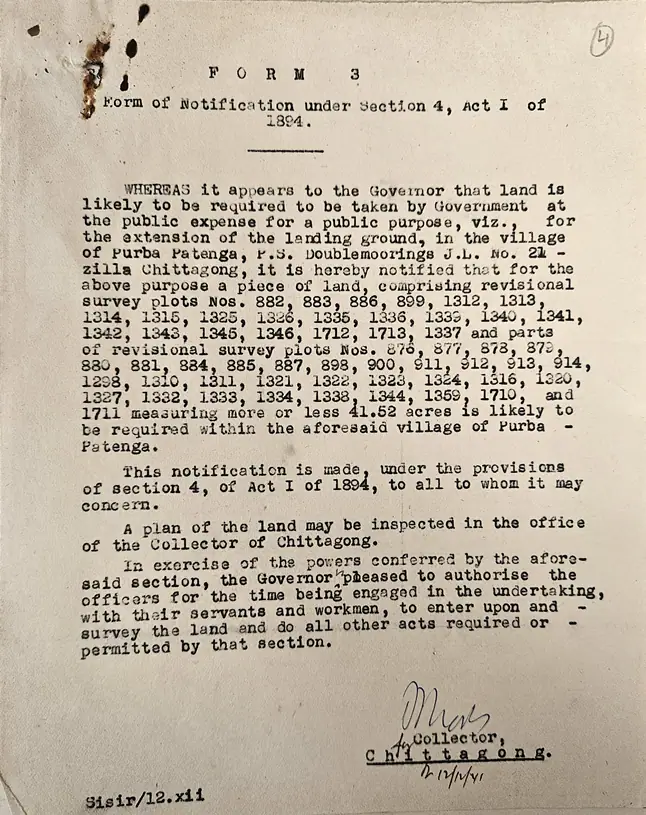

On 12 December 1941, just days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and their rapid advances in Southeast Asia, the Collector of Chittagong, T.B. Jameson, wrote to the Commissioner of Chittagong Division, requesting the immediate acquisition of 41.52 acres of land in the village of Purba Patenga. This land was urgently required for the extension of a landing ground, meant for the Royal Air Force (RAF).

The urgency was unmistakable: “The whole area under acquisition is arable,” wrote B.L. Ghosh on behalf of the Collector. However, the war effort could not wait. The colonial administration sought waivers on land acquisition procedures, bypassing bureaucratic delays under Section 5A and Section 17(1) of the Land Acquisition Act, citing military necessity.

The process was swift. By 15 December 1941, just three days after the initial letter, the Commissioner’s office forwarded the land plans and declarations to the Government of Bengal’s Home Department, seeking immediate publication in the Calcutta Gazette. Handwritten notes show the file quickly passed through the Political (Pol.) Branch, with orders to bypass ordinary procedures as allowed under Rule 79 of the Defence of India Rules, amended specifically to accommodate wartime urgency.

On 25 December 1941, the Government of Bengal officially issued the acquisition orders, noting the strategic role of Chittagong as a defence outpost. One memo read: “It is not necessary to follow the ordinary L.A. [Land Acquisition] procedure in this case in view of the amendments made…”

The documents also clarify that 20 of the 41.52 acres were already Khas land—state-owned—while the rest had to be acquired from private holdings. The urgency and authority with which the administration acted speak volumes about Chittagong’s unexpected centrality in the Allied war effort against Japan.

The Legal Shortcut: Sections 5A and 17(1)

Normally, under Section 5A of the Land Acquisition Act, affected landowners had a 30-day window to file objections, present their case, and be heard by the Collector. This clause protected the rights of citizens, ensuring that acquisition for “public purpose” wasn’t done arbitrarily.

Section 5A (1): Any person interested in any land notified for acquisition may, within thirty days, object to the acquisition.

Section 5A (2): The Collector must hear these objections and submit a report to the appropriate Government, whose decision shall be final.

However, in cases deemed urgent by the government, Section 17(1) gave the Collector sweeping powers:

Section 17(1): In cases of urgency, the Collector may take possession of the land 15 days after a public notice, even before compensation is awarded. The land then vests absolutely in the Government.

In this case, both protections were set aside. The Commissioner of Chittagong and the Home Department in Calcutta issued rapid approvals. The normal hearing period for objections was waived, and possession was ordered under special wartime powers granted by the Defence of India Rules, specifically amended through Rule 79.

Why Chittagong Mattered

Today, Patenga is known more for its beach and port activity than military history. But these files tell a different story—one in which Chittagong became a crucial wartime logistics hub, especially after the fall of Rangoon in 1942, which made Bengal’s eastern coastline the frontline of Allied defence.

This expansion of the landing ground was part of a broader imperial strategy to convert Bengal into a supply and evacuation corridor for British and Allied troops. Chittagong became a staging ground for military flights, and later, for US and British air operations in the Burma theatre.

Japanese air raids targeted the Patenga aerodrome in April and May 1942, and again on 20 and 24 December 1942.

Patenga Airfield ( also known as Chittagong Airfield) was officially designated a Bangladeshi airport in 1972 following the Liberation War. Today, it is known as Shah Amanat International Airport and continues to serve as a vital transportation hub.

To learn more about Patenga’s role in World War II, read the article Patenga’s Role in World War II.

A Forgotten Chapter

This story—buried in government memos, handwritten annotations, and colonial legalese—is a missing chapter in Bangladesh’s wartime history. It reveals how local landscapes were reshaped by global geopolitics, how citizens’ rights were suspended in the name of empire, and how Chittagong became a key node in the Allied war effort—not by choice, but by decree.

In the shadow of war, fields became runways, villages became targets, and ordinary people became part of a world conflict they never chose to join.

Author: Shamsuddoza Sajen, Chief Archivist, Bangladesh on Record