Shahnaj Husne Jahan

Born on October 1, 1918, in the village of Darikandi under Bancharampur upazila in Brahmanbaria, Bangladesh, Abul Kalam Mohammad Zakariah received his Matriculation Certificate in 1939 from Brindaban High School in Bancharampur and Intermediate Certificate in 1941 from Dacca Intermediate College (currently Dhaka College), Dhaka. He completed his BA (Honour’s) in 1944 and MA in 1945 from the Department of English, University of Dhaka.

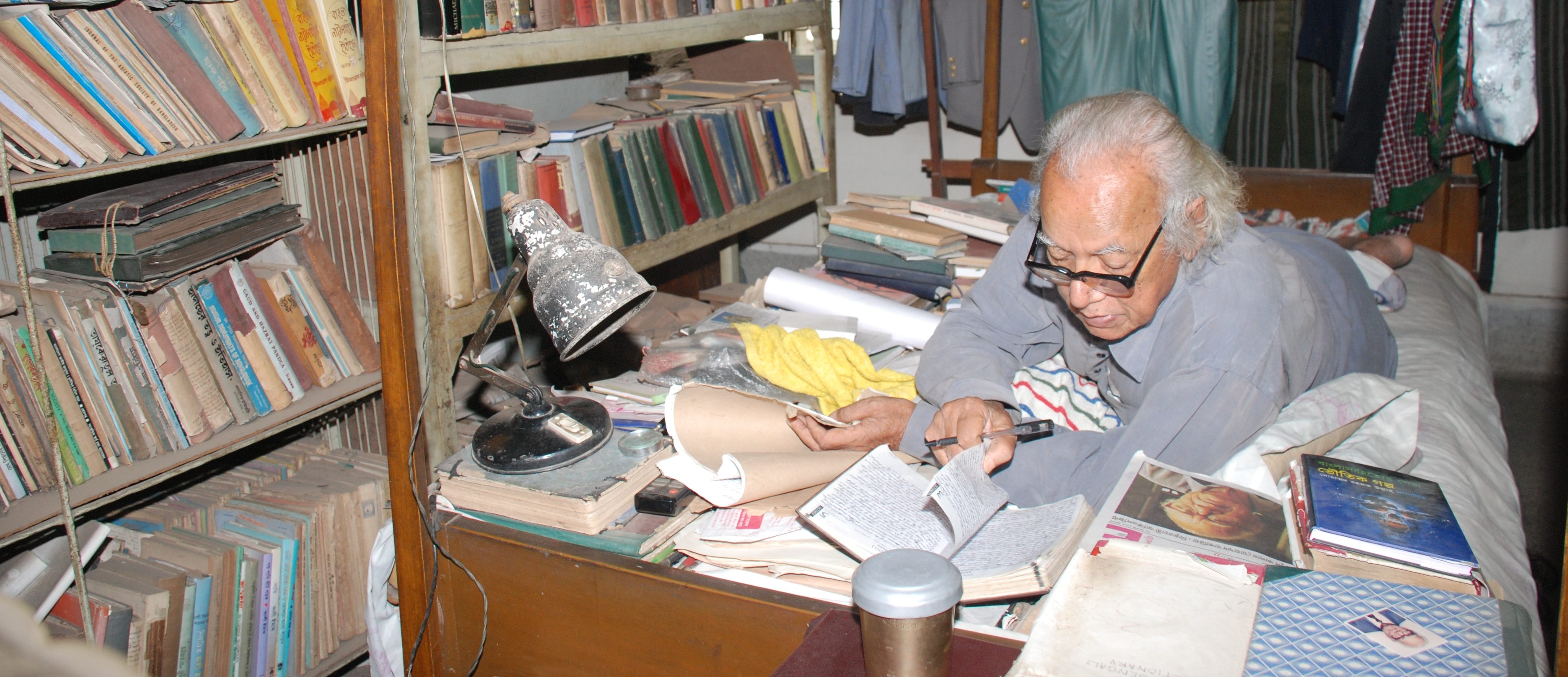

In 1946-47, during the last days of the British Raj when he was serving as a lecturer at the Department of English Language and Literature in Azizul Haq College, Bogura, he found himself drawn to Mahasthangarh, a few kilometres from his college. The site fascinated the young academic, then in his late twenties, so much so that he began to pursue scholarly research on history, archaeology and art history of Bengal in particular and world archaeology and antiquities in general. But there were not enough books. An incessant desire to “touch” the past turned into a passion and he began to investigate antiquities in the neighbouring region. Undoubtedly, Mahasthangarh was a compelling experience in his life, an experience that would lead to a tectonic shift in his living. From then on, an insatiable urge to uncover the past—“un-erase” the erased—drove him relentlessly.

After Pakistan was created in 1947, he joined the civil service and, for the first ten years, served in various administrative posts: as a Deputy Magistrate in Manikganj, Faridpur, Noakhali and Chattogram, and a Sub-Divisional Officer in Chattogram and Cox’s Bazar. In a country where one encounters civil servants either in the guise of “brown men with white masks” or as corrupt officials filling up their own coffers, Zakariah was an exception. He was a man of impeccable honesty in financial matters and was meticulous in his role as an administrative functionary, but he also used—or rather “misused”, one may say—his office for archaeological investigations. Importantly, the office provided him with a limitless opportunity to explore the archaeological sites in all areas of his posting.

In 1958, when he was posted as the Joint Collector (Revenue) of Dinajpur district, he visited most of the archaeological sites in the region. The same year, when he won a scholarship to study public administration at the California State University, USA, his passion for archaeology drove him to the Petrified Forest in California. It was a memorable experience for him, for how often does one wander in a past frozen as a forest of felled trees?

After returning home and spending a few more years in the administrative service, Zakariah drove headlong into an experience that would chisel his amateurish passion for archaeology into a definitive contour of hardcore professionalism. This was 1967, when he was posted as the Deputy Commissioner of Dinajpur administrative district. He had earlier visited Fatehpur Marash village at Gopalganj union, under Nawabganj police station in the district, and had instinctively realised that the site was neither a dried water tank, as Westmacott had claimed in 1874, nor the site of Sita’s second exile described in the Ramayana, as claimed by FW Strong in Dinajpur District Gazetteer (1912). He was sure that the site held the ruins of a Buddhist monastery.

Now, with enough administrative authority to pursue a scientific investigation, he urged the Department of Archaeology and Museums of the government of Pakistan to conduct excavations at Fatehpur Marash and nearby sites of Chak Junid, Chor Chakravarti, and Kantangar. However, even his administrate weight could not persuade the Pakistani government to undertake the investigation. As in numerous other cases, it declined his request by showing the same old “red card” the bureaucracy is fond of displaying: paucity of funds. At this point, Zakariah showed his mettle. He raised Rs 10,000 as grant from the District Board of Dinajpur—again, another “misuse” of authority—and invited the Department of Archaeology and Museums to extend its technical support. The fund was insufficient to excavate the entire site. Nevertheless, the result was decisive and significant, because Fatehpur Marash yielded what today is known as Sitakot Vihara, a Buddhist monastery dated to the 6th-7th century CE.

The excavation of Sitakot Vihara intensified Zakariah’s thirst for archaeological investigation. During the two years of his tenure as Deputy Commissioner in Dinajpur, from 1967 to 1969, he conducted an extensive survey in the entire northern Bengal and recorded all the archaeological sites and monuments in the region.

Besides carrying out his administrative responsibilities dutifully, he devoted himself to collecting artefacts from different parts of the greater Dinajpur district (currently the administrative districts of Panchagarh, Thakurgaon and Dinajpur). With the objective of preserving his collection, he established the Dinajpur Museum on May 1, 1968 as an institution attached to the Nazimuddin Muslim Hall and Public Library. This museum was also made the repository of artefacts unearthed from the archaeological excavation of Sitakot Vihara. Anyone visiting the museum will be struck with the rich collection it holds. During this period, he also collected several medieval vernacular texts (punthis), important among which are Gupichandrer Sanyas by Shukur Mahmud, Gaji Kalu Champabati by Sheikh Khuda Bakhsh, Bishaharar Punthi by Jagajjiban Ghoshal, Bishvaketu by Dvija Pashupati, Satyapirer Punthi by Krishna Haridash, Gaji Kalu Champabati by Halu Mir, Shri Krishna Bijay by Maladhara Basu, etc. All these texts were composed between the 15th and 18th centuries CE.

During the last few years of Pakistani rule, from 1969 to 1971, he served as the Chairman of Chattogram Development Authority. In those tumultuous days, when the people of erstwhile East Pakistan decisively sought a new horizon as their national identity, Zakariah rode the wave of the momentous time to recover a large number of artefacts and cultural materials from Chattogram. The success he had with the museum in Dinajpur led him to develop the Chattogram Anthropological Museum of the Department of Archaeology and Museums, which till today stores the materials he recovered from the region.

After the liberation of Bangladesh in 1971, the newly formed government was judicious enough in appointing him as Joint Secretary in the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport. He now had the full might of the ministry at his disposal and used the opportunity to dispatch the Department of Archaeology and Museums to complete the excavation work at Sitakot Vihara.

As Joint Secretary from 1972 to 1974 and Additional Secretary from 1974 to 1976 at the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport, he surveyed the entire country and recorded all archaeological sites and monuments. The result was monumental, because it yielded a documentation of over six hundred sites in Bangladesh in the form of a book titled Bangladesher Pratnasampad, which was published by the Shilpakala Academy in Dhaka in 1984. No archaeological documentation can ever claim to be complete, and the same is true in case of Zakariah’s work. Nevertheless, the book brought together what may be called the widest array of known and unknown sites, and exhibited the richness of Bangladesh’s past. The publication is more valuable because of the interest it raised among the non-professionals. If there is one book on Bangladesh’s archaeology that I hold fondly in my memory, it is Bangladesher Pratnasampad, because my student days were spent in retracing Zakariah’s footsteps and rediscovering the rich heritage of Bangladesh that he had documented in it.

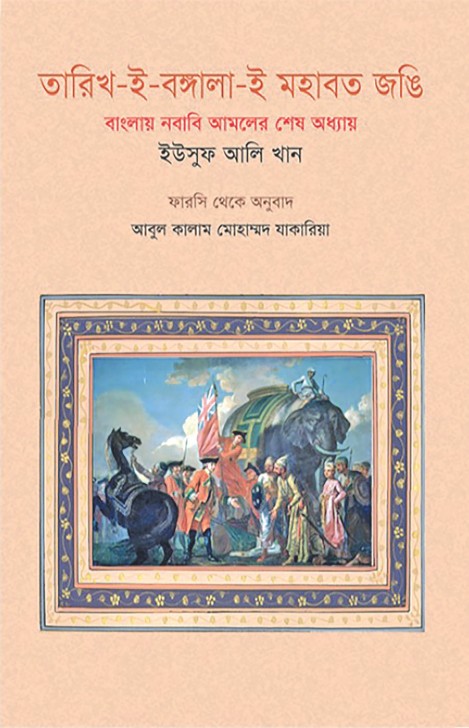

Zakariah’s professional career as a civil servant ended in 1976, when he retired as the Secretary of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport. By that time, he had enriched himself further by using his professional engagements abroad to visit numerous heritage sites in Italy, Greece, Egypt, Azerbaijan, Iran, Indonesia and India. At home, he also served as a member of the editorial board for Bangladesh District Gazetteer (1972-76), and a member of the first government committee for Mukti Juddher Itihas (the History of Liberation War) in July 1972. After his retirement, his passion for the past drew him to serve as the President of the Editorial Board of Kumilla Jelar Itihas (History of Comilla District) in 1984 and as the Advisory Editor of Varendra Anchaler Itihas (History of Varendra Region) in 1998. However, the bulk of his work in the later part of his life lay in writing. AKM Zakariah has twenty-one full-length publications, a large number of research papers, and nine unpublished novels to his credit. He also wrote on archaeology for children in two volumes titled Bangldesher Prachinkirti.

Having thus scripted the life of a man who pursued archaeology out of love, as I pause and review, I wonder if I have said enough or too little. In a country like Bangladesh, where the top-heavy bureaucracy is perhaps a little too heavy with the burden of bearing the load of a fragile economic infrastructure, and where there is hardly any fund for archaeological investigations, it has to be the people, the amateurs—and not the professional archaeologists—who provide the thrust necessary to investigate the past, either by protecting their heritage sites or by actively promoting a culture of investigating the past. The role of the professional archaeologists here must be to provide the expertise, and not turn out as the prophets who hold the key to the past. This may be a dream, but a dream worth pursuing, that I wish to work as a professional archaeologist in a country with 160 million amateur archaeologists. Zakariah stands in the forefront of such amateurs, leading by example in setting a trend that any person with a passion for the past can provide the impetus by mobilising whatever resources they may be able to access. There are more such amateurs who belong to the same breed as Zakariah, who work for passion, and because of their endeavour, one may hope for the day when archaeology in Bangladesh will achieve a household applicability as necessary as the daily bread.