Badshah-ka Takht | Bangladesh on Record

February 13, 2020

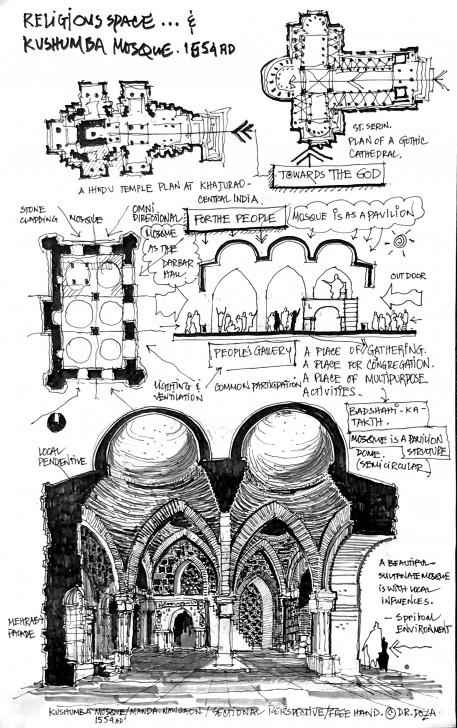

The medieval mosques of Bengal transformed from socio-political spaces to more socio-cultural zones. The mosques became part of the neighbourhood’s culture, with participation from both men and women. During the reign of the sultans, mosques were society’s central hub and the people’s main source of administration. Eventually, mosques became a platform for the public to socialise and network, even if for short time periods (waqts). The single or multi-domed medieval mosques of Bengal, such as the Choto Sona Mosque, Shat Gombuj Mosque, Darasbari Mosque and Kusumba Mosque, acted as places of congregation. These spaces were used for state governance and infrastructural development work.

Most medieval mosques in Bengal were designed by incorporating local motives and cultural ethos, and were conceptualised with the rural influence from Bengal. Traditional curved cornices, turrets (four stumpy verticals on four corners), terracotta bricks, composite terracotta, chouchala vaults etc. are the inherent elements of medieval mosques in Bengal. They are more than two stories taller than conventional buildings, and have elaborately designed hallways once you enter.

On the other hand, the ‘for the people’ approach allows the public to enter from any direction. These spaces are like pavilions where people gather for resting and praying. Only mosques fit the description of these kinds of places of abstract phenomenology. Mosques are able to uphold the glory of Islam. Therefore, abstract and non-abstract qualities both needed to be considered while constructing religious spaces. Medieval mosques of Bengal had this abstract quality since they were essentially rooms for prayer, where God is invisible and Almighty is omnipresent.

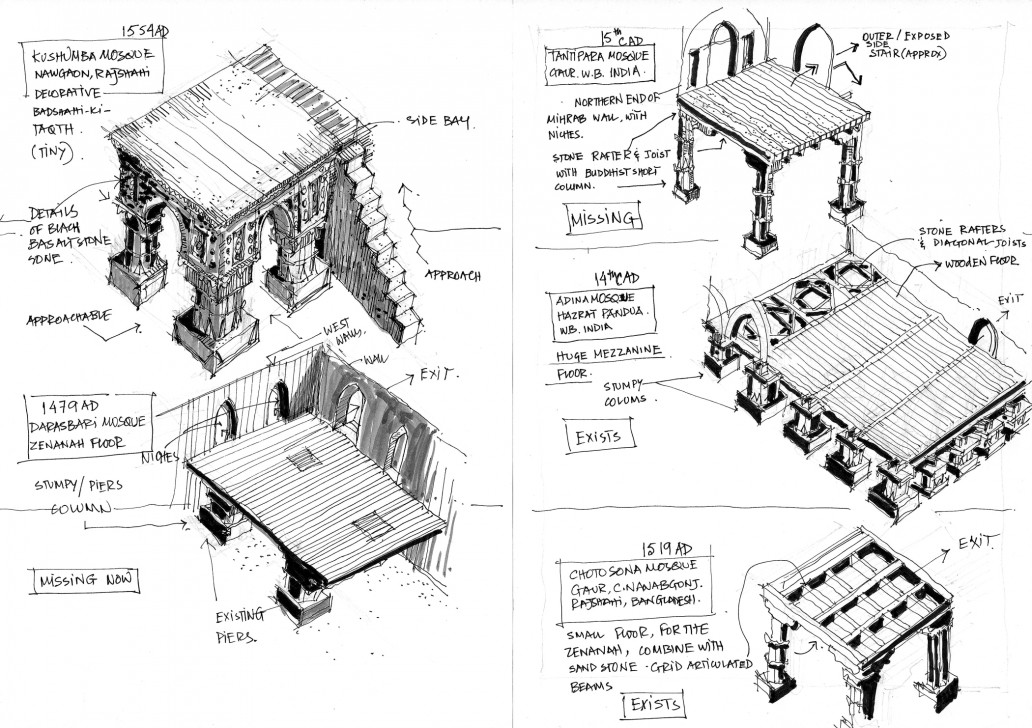

Leaders always emerge to guide the community. During the Sultanate rule, sultans adopted the cultural manners of Bengal rapidly. Their mission was to spread Islam over the hinterland, for which they began building mosques without continuing the huge construction legacy of Turkey and Iran. The advent of Sultanate rule transformed mosques into socio-administrative centres of the community. Men, women and children used to visit the mosques for counselling. Mosques therefore became public courts where a separate mezzanine or platform, which was called the Sultan’s seat or Badshah-ka Takth, acted as the throne of the sultans. The stairs of the raised platform were adjacent to the hall of the mosque.

Badshah-ka Takth should not be confused with Zenana floors. The Badshah-ka Takth is used by the sultan only for the public audience, and only one step is built inside the hall, in front of this special platform. If the step is built from outside of the hall, it is probably leading towards the Zenana floor. This special floor eventually becomes multipurpose.

The Kusumba mosque is an ideal example of the integration of Badshah-ka Takth. Kusumba Mosque is named after the village of Kusumba, under the Manda upazila of Naogaon district, on the west bank of the river Atrai. It is inside a walled enclosure with a monumental gateway that has standing spaces for guards. It was built during the period of Afghan rule in Bengal under one of the last Suri rulers Ghiyasuddin Bahadur Shah, by one Sulaiman who was probably a high ranking official. The inscription tablet in Arabic (only the word ‘built by’ is in Persian) dating the building to 966 AH (1558-59 AD) is fixed over its eastern central entrance. Although built during Suri rule, it is not influenced at all by the earlier Suri architecture of North India, and is well grounded in the Bengal style. The brick building, gently curved cornice, and the engaged octagonal corner towers are typical features.

The volume of space inside a spiritual structure is an important factor. As people enter the Kusumba Mosque, they are met with a large space that houses a separate platform in the end. The platform, which used to act as the throne for the Sultans, is the main focus of the area.

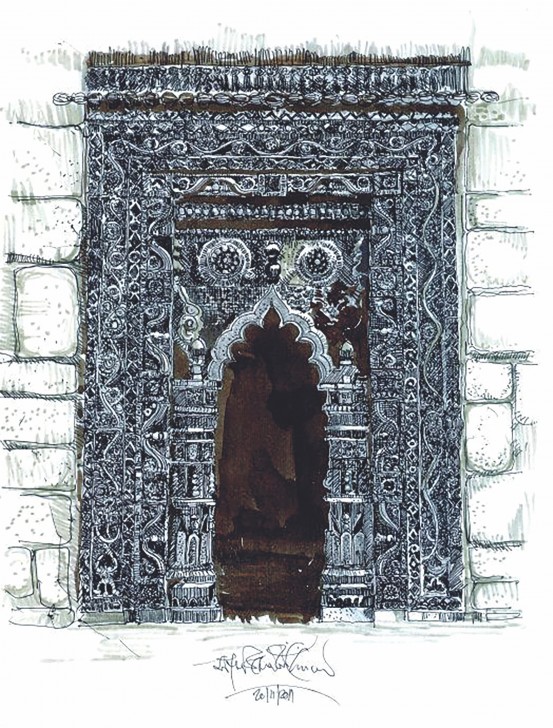

The stone raised platform, situated at the north-eastern corner of the hall room, is followed by a single flight staircase from the front. The entire platform is ornate with floral chiseling on black basalt stone works. Stone rib beams have been used at the back. The structural lines are of black sand stone. The heavily decorated Badshah-ka Takth also contains a small decorative mihrab. The platform looks like a giant table inside the hall. Badshah-ka Takth is a unique emblem of the medieval mosque, in mosque architecture. Another mosque with such a platform is the Adina Mosque of Pandua, West Bengal India (1365AD) which is one of the greatest mosques of the sub-continent. It contains a huge platform which can be approached using a ramp from the west-northern part of the mosque.

The mihrab of Kusumba Mosque is designed with precious stone curving, with précised stone coiled and chiseled on the glazing black basalt stone. This mihrab art is meticulous and unique to Bengal’s mosque architecture. In the West, this artistic development on stones, containing abstract and floral artwork with intense, rich engraving on the stone, is still evident.

Even though Kusumba Mosque is quite a small establishment, it used to be a place of justice; a domicile for the common people of this land and a system to run a provincial government, with the sultans seated on the Badshah-ka Takth. The mosque is now a great tourist site, with locals visiting during winter time. We must be aware of this cultural heritage of our country, and learn more about its historic practices.