Reminiscences of a Sundarbans mart | Bangladesh on Record

July 4, 2020

Time hath, my lord, a wallet at his back,

Wherein he puts alms for oblivion ,

A great-sized monster of ingratitudes,

Those scraps are good deeds past: which are devour’d

As fast as they are made – forgot as soon as done .

– Shakespeare

Topographical researches show that before the period which human memory at the present day can trace, the city of Selim with its neighbouring kingdom of Sonargaon, now transformed into the second capital of Bengal, constituted the furthest land limits in Eastern Bengal, south of which was the sea, known to some as the far-famed Sugandhya. The regions which nature by her gradual process of upheaval threw up in these waters were for ages the bed of the fairy tree , Sundari, which subsequently gave to the tract the name of Sundarbans. There are remains here and there, in the jungle, of human habitation which points to the existence of prosperous villages in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. During the time of the great Emperor Akbar , the tract formed an important Chakla or principality of which there is mention in the famous book of Todar Mal. Places here and there within the area, owing to the freaks of nature, again relapsed into their original state. But time inspite of its fickle process of moulding and remoulding has left behind a brick or a stone which may till eternity afford delight to the archaeologist.

A tourist bound on an archaeological discovery may, during his journey, by river in one of those gigantic crafts belonging to the world-renowned Sundarbans Despatch Service , on the third day after leaving the busy Hughly, find himself anchored at a place called Jhalakathi, one of the most important marts in East Bengal at the present day.

Nearly a mile east of it steamer has to wend her way past a broken mosque with half of it buried in the river. The broken remains of the mosque, with its desolate surroundings and a cloud-capt monument, a few yards north of it,—both bearing marks of a by-gone civilisation,—cannot but attract his notice, and wondering how such structural eminences could have sprung up in the abode of tigers and crocodiles, he would have the greatest temptation to cry “ Halt ” to the master of the vessel, and get down to satisfy his curiosity. But as the rules of the Steam Navigation Company will not admit of such haltings, suiting his sweet will and pleasure, in as much as she cannot stop where there are no stations fixed for her, the following lines may to some extent meet his desire and succeed in introducing him to the arcana of forgotten kingdoms.

The place is called “Sutaluri” and the mosque is in a Saistakhani style of architecture with three domes. The slab attached to the mosque which, owing to the rapid erosion of the river, has been recently detached by the writer of these lines (1) and transmitted through the District Magistrate of Bakarganj ( Mr. F.W. Strong ICS) to the newly established Museum at Dacca for safe custody, contains an interesting inscription in Persian.

These are verses of six lines, every two lines rhyming with each other. For the edification of one not acquainted with the Persian language the following English translation may be sufficient:

In the reign of Mohamed Shah, the Protector of Religion,

Under whose justice , the world got relief,

Gholam Mohamed (or the servant of Mohamed) out of loyalty to God,

Under God’s mercy, this place of worship did build.

To give date of construction of his mosque,

Wisdom wrote; “Approved by the grace of God.”

Unlike letters of other languages, the alphabets of the significant Arabic language have numerical values attached to each, and this has given to Persian poets a grand opportunity of chronicling dates of episodes in their poems without caring for crude figures or running the risk of marring the beauty of their compositions by being too statistical. The “Abjad system of numeration,” as such calculation by means of letters is called, helps one to arrive at the date of construction of this mosque by counting the values of letters contained in the last line, which apart from being significant of numbers, is highly poetical. Nothing can be a greater consolation to the founder of a religious edifice than to know that his work is approved by the Dispenser of all things, great and good. It is a strange coincidence that the very expression,—“approved by the grace of God,”—which would afford solace to the builder of this pious work, gives the date of its construction. The values of the 16 letters contained in the expression come to “1151”, which is the date according to the Hijri era. The corresponding year according to the Christian era would be “1732.” The first line of the verses gives the name of the then reigning sovereign of India to be Mohamed Shah. History tells us that Mohamed Shah II, one of the weak successors of Aurangzeb, was then on the throne of Delhi.

The name of the founder of the mosque contained in the third line is not, however, clear. The Persian expression “Ghulam-i- Mohaamed” may either mean that the builder was one of the name of Gholam Mohamed or that he was a servant of Mohamed. Again, this latter , word “ Mohamed” may have a double signification. It may refer either to the Prophet of Arabia or to the reigning sovereign at the time. I do not think the name of the builder was Gholam Mohamed, or for the matter of that, the verses show his name at all, for a pious man does not generally like to give out his name. The builder might have been an officer of the Naib Nazim of Dacca, but in view of the fact that Sutaluri used to be a flourishing centre of trade in the days of yore it seems more probable that the mosque owed its existence to the munificence of some princely merchant of Dacca that transacted business at Sutaluri. The name of “Narayangang” given to “Sutaluri” in the Thak Map of Bakarganj bears testimony to the migration of a number of Dacca merchants to this place in the 17th century, for it was natural for the Dacca people to enhance its importance by calling it after the flourishing trading centre of their own district, which certainly Narayanganj was then as it is now. On the basis of these premises, the theory that the mosque must have been built by a merchant becomes most probable. The importance of the ‘Narayanganj” of the Sundarbans comes out in bold relief when it is remembered that it is in the immediate vicinity of “Baruikaran”, a village now forgotten except for the existence of a few Vaidya and Shaha families, but the headquarters of the district of Bakarganj from 1765 to 1792, that is, immediately after the occupation of the country by the English.

There is no doubt that the authorities would not have chosen to build the capital of the district near Sutaluri had it not been a place of importance. During the time of the Naib Nazim of Dacca when Raja Raj Ballav’s star was in the ascendant, some officers of the Nizamat used to be stationed at Sutaluri. Inquiries show that the Zamindars of Rayerkati, a village in the Perozpur Subdivision of the Bakarganj district, a scion of whose family was decorated with the title of “Rai Bahadur” last year (namely Rai Bahadur Satyendra Nath Ray Chowdhury) are the descendants of these officers. The place acquired further importance when Baruikaran became the headquarters of the Government of the district. Even European residents were not wanting. The name of Thomas Colvin, popularly called as “Kalpin Sahib”, and Bibi Harriet are still famous in the locality.

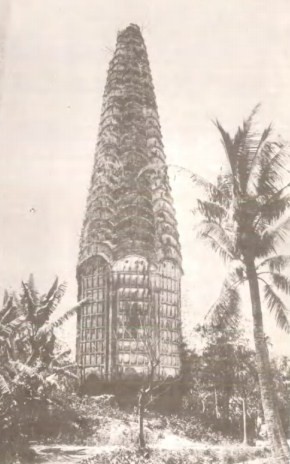

A few yards off from the mosque, as stated previously, there stands a gigantic monument, like “Teneriffe or Atlas, unremoved” called math in local patois the very sight of which is likely to send a thrill of delight in the heart of an antiquarian, ever bent on finding objects of research.The structure would be 150 yards high, and its lofty pinnacle, as if as a punishment for its insolent height, got damaged by lightning several years ago. It would appear at first sight that if the sister mosque close by had been built by a Nawab, this monument must have been erected over the remains of a Rajah or a Rani. But enquiries show that it stands over the ashes of a Shaha merchant, Durgagati Roy by name, who held from the Nawab Nazim of Dacca, 200 years ago, a license for the manufacture of salt in the Sundarbans. His descendants still exist, though in comparative poverty, and carry on trade in the Sundarbans.

Durgagati Roy was known to be extensively rich, and tradition has it, that he used to weigh money with scales. Close to the math there are other beautiful structures connected with the Hindu religion. There is no doubt that though these pious structures had been built by a man of humble origin belonging to the lower rungs of the Hindu community, their superb grandeur is still calculated at the present day to spread a halo of antiquity around them as if they had been founded by princes.

All facts go to show that Sutaluri was an important mart, where congregated men of all creeds and shades of opinion. As the Nalchiti river began gradually to cut the place, as is generally the case with all places lying at the confluence of rivers, trade began to dwindle, and the merchants, who found it difficult to leave the country all at once, removed to a place just a mile west of it, where the Bhukoilas Rajas, whose palatial buildings still exist in solemn grandeur, established a new mart, called “Maharajganj”, in the humble village of Jhalakati, so named after the Jhalos or fishermen that were the first to reclaim the Sundarbans in that locality.

Note:

The article was originally published in Dacca Review in its January, 1915 issue. [pp. 310-314]

Banner image: Bakarganj District Map, 1876.