The pioneer of rural journalism in Bengal

December 23, 2019

Ananta Yusuf

More than 150 years ago, the elite Bangalees involved in indigo production used to treat farmers and workers inhumanely.

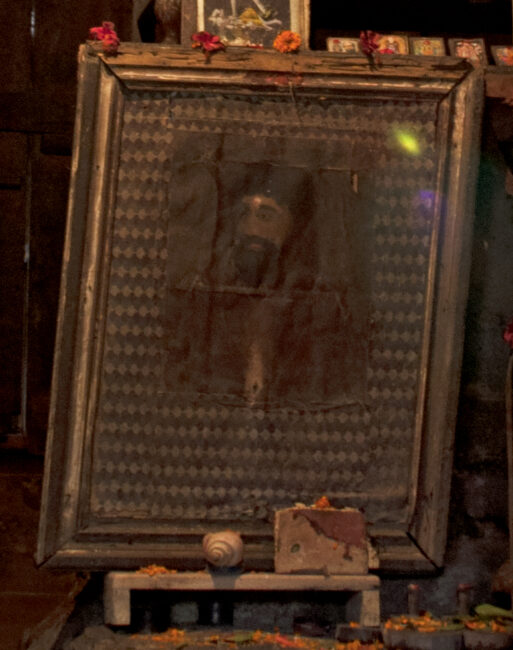

Witnessing the cruel exploitation of workers by zamindars and the British rulers, Kangal Harinath Majumder left his job at a British-owned indigo production factory and began teaching students at his small village in Kushtia.

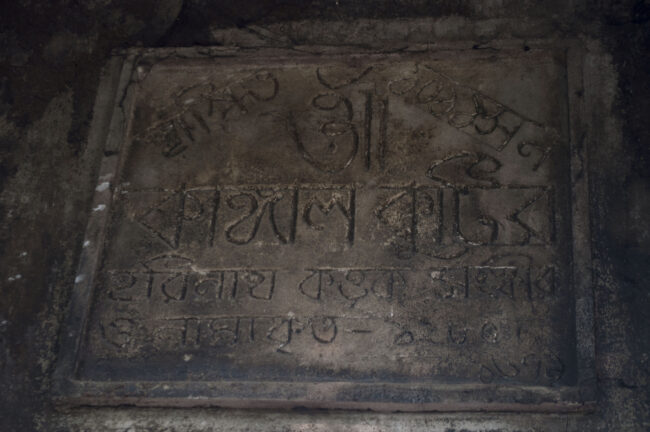

However, his conscience did not allow him to remain quiet and so he decided to fight against the atrocities by publishing news. Harinath took out a loan and put in all his savings to build a publishing house in Kumarkhali of Kushtia in 1863.

He then set out to write against the oppression of indigo farmers in Gram Barta Prokashika, a weekly Bangla publication that he founded.

This essentially made Harinath the first Bangali investigative reporter, and Gram Barta Prokashika can be regarded as the first Bangla language newspaper that directly attacked imperialists and zamindars.

Renowned author Mir Mosharraf Hossain wrote part of his classic novel Bishadshindhu at this press building in Kumarkhali. In fact, the novel and Lalon’s songs were first published in Gram Barta Prokashika.

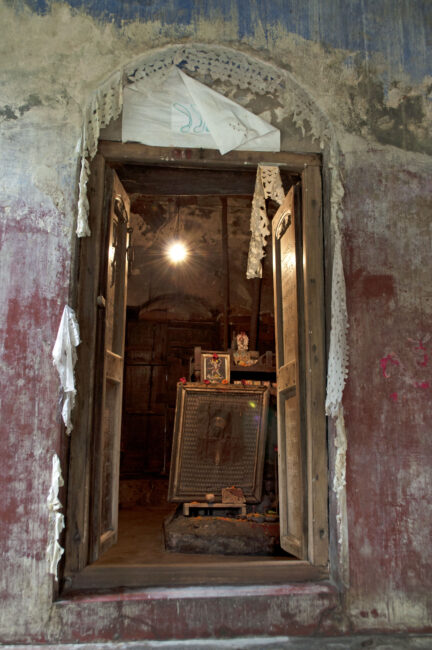

Amazingly, the printing press still functions today though the building is in a very shabby condition. The printing blocks and pages printed back in the 19th century have not been damaged much.

The publications were printed in hand-driven machines. Alphabets would be arranged in a frame and then printed on paper. It would take hours for the ink to dry and probably a day to print a small publication.

Amazingly, the printing press still functions today though the building is in a very shabby condition. The printing blocks and pages printed back in the 19th century have not been damaged much.

The publications were printed in hand-driven machines. Alphabets would be arranged in a frame and then printed on paper. It would take hours for the ink to dry and probably a day to print a small publication.

Three workers were required to print a single page; one person would arrange alphabets in the correct order in a dais, another would place pages on the dais and press them against the alphabets to get the printing done while the third person would dry the pages. Someone else would bind them to form a whole publication.

It is difficult to imagine such an arduous process in today’s world with all modern technologies and digitisation.

According to Harinath’s descendents who live just beside the press building, the printing machine that might not be found elsewhere in the country can still print 300 pages a day.

But like the building, the press has been decaying because of a lack of funds. Every time it rains, the press becomes damp due to leaks in the ceiling.

The government has recently allocated Tk 6 crore to build a museum in Kumarkhali to preserve the press.

But Harinath’s present generations, who have been struggling to preserve his legacy with whatever resources they have, are not comfortable with the government’s plan.

Of the fifth generation, Debashish Majumdar said, “We are happy that the government has taken up this museum project. But I think the museum should be here in Kangal Harinath’s press building.”