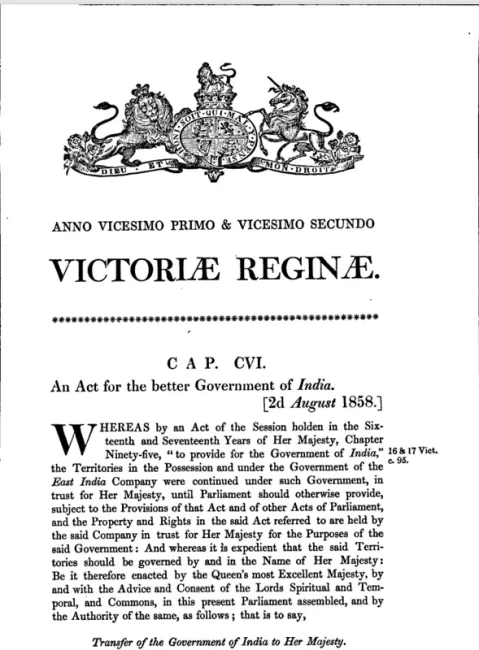

The Government of India Act of 1858 stands as a pivotal moment in the history of British colonial rule in India, marking the end of the East India Company’s dominance and the establishment of direct control by the British Crown. Enacted on August 2, 1858, this legislation was a direct consequence of the Sepoy Revolt of 1857, a widespread uprising that exposed the vulnerabilities of the Company’s administration and necessitated a fundamental restructuring of governance in India. While the revolt itself was suppressed, it catalyzed significant administrative reforms, reshaping the colonial framework and redefining the relationship between Britain and its Indian territories. This article explores the background, provisions, and implications of the Government of India Act of 1858, highlighting its role in transforming the governance of British India.

Background: The Sepoy Revolt and the Decline of the East India Company

The Sepoy Revolt of 1857, often referred to as the First War of Indian Independence, was a watershed event that shook the foundations of British rule in India. The uprising, triggered by a combination of cultural insensitivity, economic grievances, and political discontent, revealed the East India Company’s inability to effectively govern its vast territories. The Company, a commercial entity granted a royal charter in 1600, began its transformation after the 1757 Battle of Plassey and the 1765 Diwani grant of Bengal, which gave it control over revenue collection. These events marked its shift from trade to territorial rule, enabling it to administer vast regions through a complex bureaucracy and a powerful private army. However, by the mid-19th century, its administrative inefficiencies, corruption, and failure to address local grievances had eroded its legitimacy.

The revolt underscored the need for a more centralized and accountable system of governance. Even before 1857, the British Parliament had been gradually curtailing the Company’s autonomy through a series of legislative measures, beginning with the Regulating Act of 1773 and followed by successive Charter Acts (1813, 1833, and 1853). These acts progressively reduced the Company’s political and commercial powers, transferring greater authority to the British government. By 1853, the Company had become a shadow of its former self, functioning more as an administrative agent of the Crown than an independent entity. The Sepoy Revolt provided the final impetus for the British Parliament to assume direct control, culminating in the passage of the Government of India Act of 1858.

Key Provisions of the Government of India Act, 1858

The Government of India Act, 1858, fundamentally restructured the governance of British India by abolishing the rule of the East India Company and transferring its powers to the British Crown. The Act dismantled the dual authority previously exercised by the Company’s Court of Directors and the Board of Control, establishing a more streamlined and centralized administrative framework. Below are the key provisions of the Act:

Transfer of Power to the Crown

The Act formally ended the East India Company’s political and administrative authority, transferring the governance of India directly to the British Crown. This marked the beginning of the British Raj, a period of direct imperial rule that lasted until India’s independence in 1947.

Establishment of the Secretary of State for India

The Act created the office of the Secretary of State for India, a cabinet-level position responsible for overseeing Indian affairs. The Secretary of State was empowered to make decisions on behalf of the Crown and was assisted by a Council of India, comprising 15 members. At least nine members of the Council were required to have served or resided in India for at least ten years, ensuring that the body included individuals with firsthand experience of Indian administration. The Council’s role was advisory, but its consent was mandatory for matters related to the appropriation and expenditure of Indian revenue.

Role of the Governor-General and Viceroy

In India, the Governor-General was designated as the personal representative of the Crown and was conferred the additional title of Viceroy, an honorific that underscored the symbolic link between the British monarchy and its Indian empire. The Viceroy was responsible for implementing the policies of the Secretary of State and governing India in accordance with directives from London. The Act also outlined the process for appointing the Governor-General and members of his Executive Council, requiring the approval of the Council of India for ordinary appointments. However, the Secretary of State retained the authority to act independently in urgent or confidential matters.

Abolition of the East India Company’s Administrative Structure

The Act dissolved the Company’s Court of Directors and Board of Control, which had previously shared responsibility for Indian governance. The Secretary of State in Council assumed full authority, streamlining decision-making and eliminating the inefficiencies of the Company’s dual governance model.

Continuity in Administration

While the Act introduced significant structural changes, it ensured continuity by retaining much of the existing administrative machinery in India. The Governor-General’s Executive Council, provincial administrations, and the Indian Civil Service remained largely intact, albeit now under the direct oversight of the Crown.

Implications of the Government of India Act of 1858

Superficially, the Government of India Act of 1858 might appear as a mere change in the titular authority governing India, replacing the East India Company with the British Crown. However, its implications were far-reaching, fundamentally altering the nature of colonial rule in India. The Act introduced a more centralized and accountable system of governance, aligning India’s administration more closely with British imperial interests. Below are some of the key implications:

Centralization of Authority

The transfer of power from the East India Company to the Crown marked a shift from a decentralized, commercial enterprise to a centralized, state-controlled administration. The Secretary of State for India became the primary authority, with the Viceroy acting as his agent in India. This ensured that Indian policy was more closely aligned with the priorities of the British government, reducing the autonomy previously enjoyed by the Company.

Increased Accountability to Parliament

By placing Indian governance under the direct control of the Crown, the Act made the administration of India more accountable to the British Parliament. The Secretary of State, as a member of the cabinet, was answerable to Parliament, ensuring greater scrutiny of colonial policies. This was a significant departure from the Company’s relatively insulated governance, which had often prioritized commercial interests over administrative responsibility.

Symbolic Significance of the Viceroy

The conferment of the title of Viceroy on the Governor-General emphasized the symbolic connection between the British monarchy and its Indian subjects. While the title was largely ceremonial, it underscored the imperial nature of British rule and aimed to legitimize colonial authority in the eyes of both British and Indian audiences.

Continuity and Stability

Despite the structural overhaul, the Act ensured continuity in the day-to-day administration of India. The retention of existing institutions, such as the Indian Civil Service and the Governor-General’s Council, minimized disruption and allowed the British to maintain control in the aftermath of the 1857 revolt. This pragmatic approach helped stabilize the colonial administration during a period of uncertainty.

Impact on Indian Society

The Act had profound implications for Indian society, as it marked the beginning of a more interventionist phase of British rule. The Crown’s direct involvement led to increased efforts to consolidate control, including reforms in land revenue systems, legal frameworks, and military organization. The Act also paved the way for the issuance of Queen Victoria’s Proclamation of 1858, which promised equal treatment for all subjects, regardless of race or religion, and aimed to address some of the grievances that had fueled the 1857 revolt. While the proclamation was largely symbolic, it set a tone for subsequent colonial policies.

End of the Company’s Legacy

The dissolution of the East India Company’s political authority marked the end of an era. The Company, which had played a central role in shaping British colonialism in India, was reduced to a historical relic. Its commercial operations continued on a limited scale until its complete dissolution in 1874, but its political influence was extinguished by the Act.

Challenges and Limitations

While the Government of India Act of 1858 introduced significant reforms, it was not without challenges and limitations. The centralization of authority in the hands of the Secretary of State and the Viceroy created a hierarchical system that often stifled local initiative and responsiveness. The Council of India, while intended to provide expert advice, sometimes became a bureaucratic bottleneck, delaying decision-making. Moreover, the Act did little to address the underlying grievances of the Indian population, such as economic exploitation and lack of political representation. The promise of equality outlined in Queen Victoria’s Proclamation remained largely unfulfilled, as British policies continued to prioritize imperial interests over Indian welfare.

The Act also failed to anticipate the growing nationalist sentiment that would emerge in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While it stabilized British rule in the short term, the centralized and authoritarian nature of the new system sowed the seeds for future discontent, as Indians increasingly demanded a greater role in their own governance.

Conclusion

The Government of India Act of 1858 was a landmark piece of legislation that reshaped the governance of British India, marking the transition from Company rule to direct Crown control. Prompted by the Sepoy Revolt of 1857, the Act abolished the East India Company’s authority, established the office of the Secretary of State for India, and redefined the role of the Governor-General as the Viceroy. While it appeared to be a mere change in administration, the Act had profound implications, centralizing authority, increasing parliamentary oversight, and laying the foundation for the British Raj.

The Act was a pragmatic response to the challenges exposed by the 1857 revolt, ensuring greater stability and control for the British in India. However, it also highlighted the limitations of colonial governance, as it failed to address the deeper aspirations of the Indian people. As a turning point in India’s colonial history, the Government of India Act of 1858 set the stage for the complex interplay of imperial control and emerging nationalist movements that would define the trajectory of British India in the decades to come.