The Long Transition in Bengal Sufism: Onto-Theological Debates and Colonial Margins

Tahmidal Zami and Nizam Ash-Shams

Abstract

The colonial transition brought massive ideological upheavals in Bengal Islam, with the mainstreaming of a political ideology oppositional to the received politico-spiritual dispensation. The reformist rhetoric through which this oppositional ideology was articulated was based on a modern scripturalist turn initiated by Shah Wali-Allah Dehlavi, but it was also shaped by bigger onto-theological debates in the longer history of Islam. In this paper, we trace how the grand onto-theological debates, such as the debate on wahdat al-wujud vs. wahdat ash-shuhud, were overdetermined by the encounters between Islam and its others at various intersection points between crisscrossing flows traversing a wide geography. This article explores this question in relation to the expansion of the Nizampuri-Azamgarhi Tariqah – a reformist Sufi order across the Bengal-Arakan frontier linking South and Southeast Asia. The order spread its roots to Arakan based on preexisting Muslim network consolidated by increasing migration on the back of a rice export economy. The departure of the British colonialists and formation of post-colonial states led to refrontierization at the Bengal-Arakan border, giving rise to politicization of identities and new intensities of violence which decimated the Sufi diaspora in Arakan.

Keywords: Sufism, Bengal, Arakan, Syed Ahmad Berelvi, Colonial transition

Introduction: The Oppositional Paradigm in Islam during the Colonial Transition

In the gallery of major figures in Indian Islam – aside from Sufi masters like Muin al-Din Chishti (1143-1236 CE) or Nizam al-Din Awliya (1238-1325 CE) – there are hardly anyone as impactful as Shaikh Ahmad Faruqi of Sirhind (1564-1624 CE) and Shah Wali-Allah of Delhi (1703-1762 CE).

The Chishtiyya and Suhrawardiyya Tariqahs – followed by Qadiriyya and a few others – were key actants in Islamization and spread of Sufi networks in North India and Bengal. Some of these Tariqahs – especially the Chishtiyya – developed a language of intersectionality in relation to the vast and multifarious populace of India upholding a panoply of beliefs. With the advent of Mughals from central Asia, the Naqshbandiyya Tariqah from the same region found a stronger foothold in India. The Mughal regime under Jalal al-Din Muhammad Akbar (r. 1556-1605 CE) was developing a vast apparatus of power centered on politico-spiritual charisma of the Timurid household and bringing together multiple religious and ethnic groups under a system of common allegiance and vocabulary of power. Using the same millenarian logic, the Naqshbandi saint Shaikh Ahmad Faruqi of Sirhind articulated a resounding critique of the politico-spiritual strategy of the Mughal apparatus. Proclaiming himself the renovator of the second millennia of Islam or the Mujaddid-e Alf-e Thani, Ahmad Sirhindi attacked in the same breath the political promiscuity of the Mughals and the intersectional Sufi praxis of the Indo-Muslim saints.

By putting up a formidable opposition against the Mughal empire at its heyday in the name of Islamic orthodoxy, the Mujaddid remobilized the old Islamicate dialectic of the ruler vs. the man of religion. By enacting an implacable opposition against the Emperor’s religio-political policies that would subsequently create greater resonance compared to its alternatives, the Mujaddid’s name came to be enshrined as the representative of the orthodox current in Indo-Islam. The Mujaddid created a symbolic place for oppositional Ulama, representing the orthodox reaction against various ideas and practices that he deemed heterodox. Like the West Asian intellectual Ibn Taimiyyah, the Mujaddid revived an oppositional paradigm in Indo-Islam.

The Mughal establishment sought to accept, assimilate and neutralize the symbolic aggression of Ahmad Sirhindi the Mujaddid. However, following the death of Aurangzeb (r. 1659-1707 CE), the Mughal establishment began crumbling under its own logic of growth. The Mughal urban network became populated with new ethno-religious and socio-economic groups wielding increasing power such as networks of merchants and bankers as well as ulama and Sufis linked with the Islamic heartland. Ethno-political groups like the Marathas, Sikhs, Jats, or Afghans became armed threats to the Mughal monopoly of power consisting of the Turko-Irani-Rajput complex.

When the pax Mughalica was definitively shattered, the Islamic intelligentsia came up with new responses.

It was Shah Wali-Allah (1703-1763 CE), a brilliant scholar born in an ancient Muslim family of Delhi, who articulated a new critique of the existing Indo-Muslim politico-spiritual strategies and in so doing brought about a scriptural reduction and ideological reconfiguration of doctrinal Islam in India. Like his Hijazi contemporary Muhammad Ibn al-Wahhab of Najd (1708-1792 CE), Wali-Allah revived ijtihad (interpretive jurisprudence), challenged blind imitation of fiqh schools, and prioritized the scripture and prophetic tradition (Quran and Sunnah). While Shaikh Ahmad the Indian renovator had earlier been denounced, even proclaimed kafir, in the Islamic heartland of Mecca-Medina, Wali-Allah came up with a more powerful and global program of Islamic reform. Having performed a pilgrimage to Mecca during 1730-33 CE, Wali-Allah returned to India and proclaimed himself the Mujaddid of the era whose verdict must be followed by the political and spiritual elite. At the center of a Mughal state helpless against the aggressions of the new ethno-political forces and spiritual heterogeneity, Wali-Allah wanted a reassertion of Sunni dominance by conceiving an abstract, almighty authority of God and prescribing an ideological purity cleaning up the accretions of innovations in Indo-Muslim life as well as a political strategy centered on the consolidation of a chaste Sunni administration that would quash Hindus and Shiites with overwhelming violence. Wali-Allah saw society as an evolving order that would climax into a universal caliphate, just as God himself reigns on the divine court (mala’ al-a’la) (1). In the declining Islamic realm of the late Mughals, Wali-Allah initiated a new transcendence, unhinging the emplaced notions of religion, governance, and culture.

Within a few decades of Wali-Allah’s death, the Mughal emperor was turned into a mere pensioner of the East India Company. The successors of millenarian oppositionalism came up with political responses suited to the new context. Wali-Allah’s able son Shah Abd al-Aziz declared India an abode of war (dar al-harb), further displacing and deterritorializing the Islamic imaginary from its emplaced Indian context. However, while he considered eliminating infidels a virtue in the vein of his father, he also supported leading a functional socio-economic and religious life under infidel rulers as much as possible (2).

Sayyid Ahmad Berelvi (1786-1831 CE) was an epochal figure in this new chapter of Indo-Muslim society (3). He combined futuwwa ethic of heroic militancy, Shah Wali-Allah’s reformist puritanism, a trans-Tariqah Sufi charisma (4) and a millenarian vision of his mission in the crumbling Muslim religio-political geography of India in early 19th century.

He found a powerful comrade in the figure of Muhammad Ismail, an erudite ideologue and scion of the Wali-Allahi family. In the works of Muhammad Ismail and other members of Tariqah-i-Muhammadiya (TiM), religious duties like jihad were obligatory upon each Muslim, not a delegatory obligation for the whole community. Sayyid Ahmad couldn’t launch exoteric (zahiri) jihad from a dar al-harb – since their goal was not rebellion – but only from an abode of security (dar al-aman), following the prophet’s model. Propaganda on orthodox praxis among Muslims in occupied India was meant to result into migration to the frontier and war (5). Berelvi waged a war in the Northwest frontier against the Sikhs. However, hostility from the local Pashtuns and modern military tactics of the European-led Sikh army led to a devastating end to his jihad in 1830 CE. Despite the quick and bloody abortion of his revolutionary program, Berelvi left an undying legacy and paradigm for Indian Muslims.

A few factors strengthened Syed Ahmad Berelvi’s legacy despite his military defeat. He had reenacted the old Sirhindian oppositionalism by combining religious orthodoxy and political opposition within the ideological frame of tariqat. Being a Sayyid, he mustered the symbolic prestige of Shah Wali-Allah through his pledge of allegiance (baiah) to Abd al-Aziz as well as in the figure of his loyal comrade Muhammad Ismail. He pursued his cause with considerable zeal and traversed the expanse of Hindustan to gather recruits. His visits to Kolkata caused stirs among the Muslim notables and gentry and eventually he managed to gather a diverse body of Indo-Muslim followers to wage jihad in the northwest. At his martyrdom in battlefield, his followers dispersed to their respective regions. It was this returnee mujahidin diaspora who carried back the oppositional mission, the prestige of Berelvi’s legacy, the claim to represent and succeed his Tariqah, and a certain fraternal solidarity (asabiyya). This formed the social basis for the supremacy of his symbolism.

Sayyid Ahmad Shahid articulated a messianic jihad movement with the help of Ismail Shahid, which raged till the 1860s. However, from 1830s onwards, gradually many of the neo-orthodox Islamic tendencies took a quietist, non-military stances and directed their efforts to reform Muslim society. Thus, the offensive posture of the messianic jihadism was replaced with the self-defensive posture of socio-religious reformism.

It was from among the successors to Berelvi that various new sub-Tariqahs emerged, one of which was the Nizampuri Tariqah of Bengal. This Tariqah played a profound role in shaping subsequent Sufism in Bengal in the colonial era.

In this paper, we would concentrate on one of the sub-families of this Nizampuri Tariqah, namely the Azamgarhi Tariqah, to explore how the suborder ultimately hailing from the TiM could expand its footprint at the furthest margin of Indo-Islam, namely the Bengal-Arakan frontier.

A fundamental methodological principle must be added here: all typological and periodization schemes are taken here as formal-discursive effects on an irreducible and immanent multiplicity. Singularities are never reducible to the categories of universals and generals, just as difference is prior to identification. The schematic discussion presented here needs to be read with this epistemological ethic of prioritizing immanence, multiplicity, and irreducible difference. For example, individual Sufi groups need to be understood as complex and open entities radiating filiations and effects in various fashions rather than being reduced to spacetime, social or spiritual affiliation, avowed ideology and so on. In other words, the molecular dimension of the entities needs to be kept in mind no less than the molar dimension. As we will see, the vicissitudes of development of the Nizampuri-Azamgarhi Tariqah was complex and aleatory and cannot be understood in the teleological or essentialist notions about Indo-Islam, economic determinism or frontiers.

A New Sufism for Bengal: The Case of the Nizampuri-Azamgarhi Tariqah

In this section, we analyze the case of the Azamgarhi Tariqah to see how a Sufi order expanded in the Chattogram-Arakan axis in the colonial period. We use existing literature on the Tariqah such as the writings of Mr. Ahmedul Islam Chowdhury, a pious adherent of the order, that represent a very interesting emic source. We also make use of fresh primary material like a few successorial documents (khilafatnamahs) which are little studied in understanding Sufism in Bengal or South Asia.

We posit that the emergence of new respectable classes and the expansion of agrarian frontier laid down the objective conditions for the reception of the Nizampuri-Azamgarhi Sufi order in new horizons, while the anti-traditionist and oppositionalist rhetoric espoused by the order – like so many other related branches of Sufi orders – were ideological formulations that aligned with the new ethical purposes and epistemological regime of the new epoch.

To put it into context: In early 19th century, Bengal was swept with a series of reformist movements. We can name the Faraidi, the Tayyuni, the Deobandi, and strands of the Tariqah-i-Muhammadia movement as the most notable. A brief description of the movements could help locate the Nizampuri-Azamgarhi Tariqah in its proper context.

The Faraidi movement was initiated by Haji Shariatullah (circa 1781-1840 CE). From rural Faridpur, he had traveled to the Hijaz and Egypt for Islamic education and returned to Bengal upon completion of studies. Shariatullah propagated an orthodox version of Islam cleansed of syncretic accretions and reduced to fundamental obligations required in scripture, yet firmly affiliated with the Hanafi school of Fiqh that was the prevalent emplaced jurisprudential tradition in Sunni Indo-Islam. His constituency was mainly the peasants and artisans of South-central Bengal (6). He maintained a broadly apolitical program, but as the Muslim peasants and artisans joined his sect, they came to blows with the local Hindu zamindars. In 1840s to 1860s, his son Muhsen Uddin alias Dudu Miyan (1819-1862 CE) expanded the movement into a consolidated network functioning both as a religious sect as well as a force of peasant resistance against landlords and the indigo farmers. Although the Faraidis never confronted the colonial administration, they prohibited congregational prayers for Muslims on the ground that a proper comprehensive Muslim municipal township (misr al-jami) couldn’t be found in Bengal, thereby contributing to the notion that Bengal was a military territory or dar al-harb. However, after Dudu Miyan’s death, the successors of the movement increasingly took a more conformist position to the colonial condition. Thus, the Faraidi movement uniquely combined a certain renovation of the Islamic religious culture, a disavowal of the political status quo, and yet a very close emplacement in the peasant society as well as the traditional jurisprudential base.

While Faraidi movement was raging, the disciples and comrades of Sayyid Ahmad Berelvi launched their operations in Bengal. The most spectacular follower of Berelvi was a wrestler turned religious preacher called Titu Mir (1782-1831) from the 24 Parganas of West Bengal. Titu’s religious preaching brought his followers into conflict with Hindu Zamindars who wanted to curtail the orthodox observance of the Muslim peasants. His small band of followers reacted to Zamindari strictures with violence. The conflict escalated rapidly till the military intervention by the East India Company regime. Titu Mir and his main lieutenants were murdered almost around the same time that the holy warriors under Berelvi at Balakot were annihilated.

Since the military campaigns of Sayyid Ahmad Berelvi and Titu Mir were destroyed by the colonial power, Berelvi’s other successors adopted a less offensive role. Some of his disciple mujahids had tried to wage war in the frontiers. Maulana Wilayat Ali (1790-1852 CE) and Inayat Ali (1794-1858 CE) from Sadiqpur family of Patna sent delegates to Bengal for propagating Tariqah-i-Muhammadiya (7). During 1830s to 1860s, TiM preachers would show up in Kolkata and rural Bengal and the province was divided into circles for propaganda and fundraising. Some propagandists of the TiM declared Sayyid Ahmad a messiah (Mahdi) who had not died and would return in the right moment. They promised a future Islamic state where land would be rent-free. Peasants of the Bengal delta joined their ranks thanks to the millenarian promise. However, it is not clear that they could recruit any significant percentage of the Bengal peasantry as fighters or supporters (8). By the 1860s, the jihad efforts were mostly subdued (9).

A more reconciliatory approach was adopted by Maulana Karamat Ali Jaunpuri (1800-1873 CE), who wrote a body of literature to reconcile Muslims to the existing political dispensation as a fait accompli. Jaunpuri had accompanied Sayyid Ahmad to Mecca but probably didn’t join the jihad (10). He began his movement in 1830s that would be identified the Taiyuni movement which found support in almost the same region as the Faraidis’ (11). In contrast to the teaching of the Faraidis, Maulana Jaunpuri encouraged holding congregational prayers. He sought reconciliation of the Tariqah-i-Muhammadiya with the four fiqh schools as well as the main Sufi orders. The old school mullahs or the sabiqis began identifying with his camp in the latter part of the century (12). In 1870, the Chief Justice of Kolkata high Court was assassinated, while the Viceroy of India Lord Mayo (r. 1869-1872) wanted to fix India’s political status from the perspective of Islamic theology, a group of ulama issued a fatwa declaring it as dar al-Islam. Jaunpuri threw in his weight, besides Nawab Abdool Luteef, declaring that India was not dar-al-harb and jihad against the dispensation was unlawful (13). Jaunpuri thus represented a pragmatist reconciliation with political reality.

The above discussion reflects that Tariqah-i-Muhammadiya (TiM) was both a highly influential as well as thoroughly contested legacy – interpreted, appropriated and denied variously by emerging theo-political tendencies. The British persecuted various such tendencies branding them under the umbrella term: “Wahhabis”. The 1857 Indian war of independence was followed by rampant persecution of the Muslim elite. The destruction of earlier jihadi military campaigns, the quietist or reconciliationist line advocated by certain leaders, and consolidation of British administration deep into the social spaces of India encouraged a change of tack for the Indian Islamigentsia. The establishment of Dar al-Ulum Deoband (1866 CE) and the Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental College of Aligarh (1875) were two expressions of the strategic reorientation.

The oppositionalism nurtured by the Islamigentsia could have two postures:

(a) At its offensive posture, it would be an assimilative opposition, whereby either the ruler would have to assimilate to the politico-ideological demands of the Shaikhs and everything would be fine, while in the event of non-alignment, the ruler could risk stiff resistance.

(b) At its defensive posture it would be an accommodative-negotiative opposition, whereby the Shaikhs would concede various political and disciplinary spaces to the regime but cultivate their own social discipline to form a quasi-political community.

In the colonial era, due to this flexibility of strategy in their engagement with power, the oppositional Islamigentsia could engage the upward aspirations and opportunism of the Muslim middle and upper strata. Of course, the oppositional Islamigentsia was not a monolithic Sufi-Ulama complex but consisted of various schools of TiM, the Faraidis, the Deobandis and so on with variegated ideas and strategies. However, these groups shared the broad assumption that socio-ideological reform was essential for the Bengali Muslims.

In the following passages, we describe some of the processes during the colonialism that created the context for a reconfiguration of Sufism in Indo-Islam.

Marginalization of Syncretism

As the reformists assumed a new kind of transcendence in relation to Indian socio-political reality, they questioned the emplaced religious culture. The so-called innovations and ‘syncretistic’ practices of the local Muslims of Bengal became a prime target of the reformists. In this vein, the age-old praxis of the local society passed under the radar of the reformists (14). Veneration of ahl al-bait or imaginary and real saints or sacred figures, quasi-magical practices of the agrarian society, and so on were all dubbed as part of polytheism (shirk). This affected the relationship between Islamic clergy and mystics with the rural lay peasantry of Bengal.

At the same time, the colonial state imposed new forms of control over the lives of the populace, controlling their consumption, movements, and expressions. The ordinary faqirs, bairagis, qalandars, bauls and so on who earlier predominantly practiced various forms of vernacular spirituality deeply rooted in the native society were seen as a mass of undesirables by the British administration. In traditional Indo-Islam, faqirs were usually understood as God-intoxicated men (majzub) whose impassioned utterances veiled a mystical reality underlying the mundane phenomena. In precolonial India the itinerant, often antinomian, vernacular qalandars and zavaleqs would traverse and interact with the network of mainstream religious and spiritual centers, as for example seen in the table-talk of Nizamuddin Auliya (15). The Faqirs practiced transgressive physical culture, such as consuming intoxicating substances and wandering naked freely and without traceability, yet enjoyed considerable social respect (16).

The colonial intervention involved epistemological violence as well as physical coercion against these sects. The colonial administration dubbed the faqirs as charlatans.

While the state overtly took a neutral and non-interventionist stance towards ‘religion’ identified as a matter of interiorized beliefs and social practices, the faqirs’ transgressive culture and political intransigence induced the British to violently attack them as a matter of sanitization of the ‘colonial space’.

Of course, the colonial space itself could never cover the entire governed territory, rather it always needed to maintain an outside – a socio-economic residual space – within or just across the borders of the inside to maintain the exclusionary and doubly exploitative nature of the colonial enterprise compared to any domestic capitalism. The administration classified the faqirs as nuisance defined in terms of their begging (unproductive life), vagrancy (untraceable life), as well as nudity, intoxication and madness (unreasonable life) (17). The colonial state tried to define what constituted legitimate form of religious subjectivity by dictating some behaviors as public nuisance, while others were accepted and even encouraged.

The colonial othering of such spiritual culture was complemented by emergence of a native puritanism – whether modern or neo-traditional.

Languages and Texts

The reconfigured Sufism was premised on a new relationship among texts, technology, and the beliefs and practices of the community of believers. Shah Wali-Allah’s Persian translation of the Quran as well as subsequent Urdu translations by his sons transformed Quran from a miraculous word of God primarily celebrated aurally into a comprehensible text to be read and understood (18). In 1830s, English replaced Persian for official language. Persianate humanism dissipated due to the change of medium of education in 1835 (19).

The administration heightened emphasis on vernacular language for schools and courts. Among Indian Muslims, Hindustani was being accepted as a more useful medium(20). The printing press gave rise to a vigorous Urdu literary sphere. In competition to Christian and Hindu literary spheres and the scripturalist polemics by missionary, the Muslim princes and wealthy patronized the press to publish and propagate Islamic literature. (21) Urdu emerged as the language of the public relations of an evolved Ulama, elevating it as the normative language for Islamicate culture and an Islamic religiolect for South Asian Muslims. The Islamigentsia successfully created a relatively coordinated grassroots-based literary-social circuit supported by the printing press and Urdu intelligibility. A new textual culture changed the hermeneutical space in Indian Islam. As a modernist Muslim public grew up, they inherited the colonial-capitalist gaze imbued with rationalist-utilitarian assumptions. Nationalism involved reform and disciplining the Muslim masses. Sayyid Ahmad Khan (22), Mir Shahamat Ali, or Allama Muhammad Iqbal came up with a new imagination of the identity and values of an Indo-Islamic community.

New Institutions

A new institutional culture underwrote the emergence of the new Muslim intelligentsia. The madrasahs established such as Kolkata Aliya Madrasah (1781) or the Hooghly Madrasah – though limited to the ashraf for a long time – gave a definite new form of educational development. Before the 19th century, many mullahs in Bengal and Bihar couldn’t comprehend even one page of Arabic. (23) The Delhi College (1825-1857), the Aligarh Institute in 1866, the Mohammedal Anglo-Oriental College in 1877 introduced new education for Muslims. (24) Deoband Madrasa established in 1867 by Muhammad Qasim Nanawtwi (1833-77) and Rashid Ahmad Gangohi (1829-1905) – two disciples of Mamluk Ali who was disciple of Muhammad Ishaq of the Delhi reformist family – emerged as a new apparatus that could provide authoritative Islamic education. (25) Deoband secured its finance by direct contributions by the Muslim community from near and far. 30 Madrasas were established in India in the model of Deoband by 1900. (26)

Although colonialism had a certain effect of deindustrialization and un-development of India, its economic and logistical conditions created certain opportunities that were grabbed by newly-emerging classes, laying down the social infrastructure of respectable classes. A social layer of maulanas, hafizes, traders, zamindars and so on composed the strata of respectability within the Muslim community.

In Bengal, just as military jihadism subsided after 1871, the British sought to assimilate the Muslims of Bengal into the existing educational-ideological structure as well as employment. They gradually integrated Muslims into schools and eventually a higher educational institution that was Dhaka University. The graduates of new madrasas created anjumans that served as organizational basis for reform work. In the place of older Sufi silsilas, these new institutions created new bases for Islamic networking.

Economic Ethic

Traditional Sufi establishments in India often conceived themselves as munificent providers – both in material and spiritual terms – to vast indigent masses irrespective of their class or creed, as captured in titles like ‘gharib nawaz’. Many towering Sufi figures in Sultanic and Mughal India did not engage in any income-earning or acquisitive work (kasb), but worked as axes of redistribution for the social surplus value, whereby the gifts and donations from disciples and city-folks would be given away to the poor masses, often irrespective of their socio-religious affiliations. In the stable atmosphere of Mughal India, land grants to Sufi establishments (madad-i-maash) became ever more common. Festivals like Urs in the Sufi shrines or rite of passage ceremonies were spiritually encoded programs for redistribution of the social surplus value through extravagant consumption and charity.

When the precolonial political economy metamorphosed into a new administrative and market structure under the impact of colonialism, a whole new social calculus came into being.

The most critical change wrought by colonialism was the resumption of rent-free grants to waqf lands, undercutting funding for many Sufi shrines and Madrasas. As colonial salariat classes replaced their Mughal predecessors, the redistributional system was reconfigured. In the new setting, an ethic of strict pecuniary accounting was encouraged while extravaganza in the redistributive festivals (marriage, Urs, and so on) was censured. The notions of respectability stressed a relationship of law-bound reciprocity with the colonial state, a structure of public institutions of education, and so on. The new social type of respectable personality was expected to be self-sufficient and law-abiding. For a Sufi, living on charity came to be seen as less respectable. The Sufi should earn their own living and should extend their hegemony on the upwardly-mobile classes.(27)

There was a certain alignment between orthodox puritanism and modernist anti-traditionalism in terms of breaking the shackles of older religious and political authorities as well as popular beliefs and practices. (28) In other words: creating a deterritorialized transcendence – sustained by the new networks of institutions, texts, and practices – from the emplaced local spiritual culture.

The partial alignment of the orthodox reformist and modernist movements produced a separate Muslim public out of sections of the Muslim peasants of Bengal, but this new ideological accretion could not penetrate too deep into the life of Muslims in Bengal. Moreover, the peasant followers of Wahhabi or TiM were still partly attached to some of their older practices. (29) Mullahs who served as the rural social authorities, magicians, and so on could not immediately be reformed into the new ways. The practical complex of the fragile life of the peasantry involved magical practices such as driving away jinns, snakes, and myriad other dangers, and no reformism or rational modernism could fill in the needs. Older social types like shamans (ojhas) or badiyas carried on the show. Just as colonial sanitization could cover only the inside of the colonial space, reformism by its ideological/practical logic could penetrate only some parts of the lifespace of Bengali Muslims.

The above describes some of the dimensions of colonial changes that enabled a reconfiguration of Sufism in Indo-Islam. We would now discuss the kind of reconfiguration that took place in the structure of Sufism.

Classical Indian Sufism had been by and large shaped by the post-Mongol consolidation of Sufism as an increasingly structured system. This involved articulation of orders defined by shared allegiance, common but flexible body of teachings, disciplinary techniques and practices, and so on. The geography would often be partitioned into Sufi domains. Public authority of Sufis was mostly orally-mediated, aural and auratic. As the emplaced, cultured intelligentsia of Islam, the Sufis undertook various adaptations, translations and negotiations of ideas and practices in relation to the heterogenous mass of Indic peoples and social groups. With a consolidated, structured reproduction of Sufi orders during the Sultanic and Mughal periods, such adaptive-translational ideas and practices gained a certain traditionalization, which would be later called rusumat or traditional practices. The oppositional mujaddid Shaikh Ahmad of Sirhind launched attacks on traditionalism during the reigns of Akbar and Jahangir. However, Shaikh Ahmad’s reconceptualization was launched within the same ethical and epistemological conditions as his detractors.

With the onset of colonialism, there was a certain de-structuration of classical Indian Sufism, and its Bengal chapter was no exception. With the political quietization of the oppositional islamigentsia, a tactical common front against old-fashioned Sufism was opened by the partially-aligned orthodox and modernist Muslims. The new colonial political space gave an impetus for vertical integration of rural Islam in Bengal with pan-Indian Hindustani Islamic ideology. A network of new Sufi darbars were established in Bengal to propagate reformism with zeal. Undoing the traditional tariqah-structuration, trans-Tariqah Sufism became much more common in this period: a Sufi receiving initiation from multiple lineages has been not uncommon since 15th century, but the process rapidly flourished under colonialism. (30)

In short, new textual culture, new educational institutions, and new structuration of life created a new form of religious intersubjectivity. New ways of interpellation a la Althusser could be devised based on this interplay among mass-circulated texts, new norms around Islamic discourse-making, and the refashioning of the Muslim selves. Of course, the dead Pirs could not be rendered interpellated by the new ideological apparatuses. Popular veneration in their tombs continued in the vein of tradition, and the reformists sought to stem this tide.

In the reconfigured Sufism, just as the Sufis were dislocated from their earlier roles of munificent public-ness, the ethical purpose of Sufism would partly be regrounded.

The Tariqa-i-Muhamadiya in its various forms, the Faraidi movement, and later the expansion of the Deobandi educational apparatus created a new ethical transcendence of Islamic men.

The new ethical purpose was cultivating a certain oppositionalism towards various forces and growths that were perceived to have attacked or enervated the collective body of Muslims.

In this context of a new conception of Sufism would we place the successor suborders succeeding the Tariqah-i-Muhammadiya (TiM). These suborders distinguished themselves against the broader context of Indo-Islam by railing against polytheism and innovations. At the same time, these sought to appropriate the prestige and sanctity of older classical Sufi orders by claiming multi-tariqah filiation.

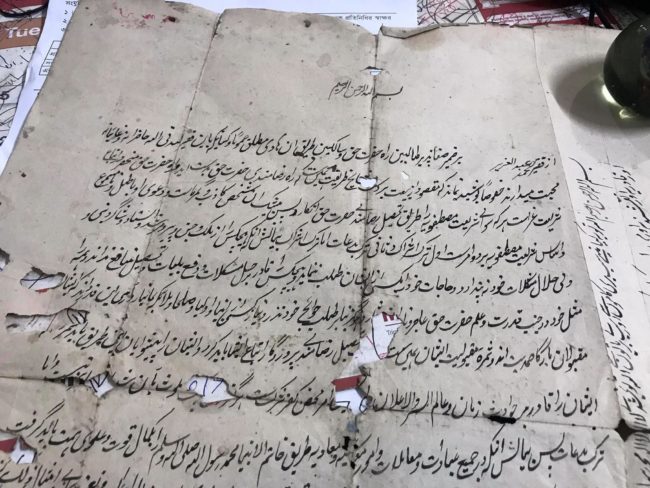

For an example of the ideas of a typical TiM suborder, we would like to quote here a succession-come-preceptory document by the successor of Imamuddin Bangali, a Bengali lieutenant of Syed Ahmad Berelvi.

To make a brief methodological remark: In understanding Sufism in Bengal and India, the predominant focus has been on texts like table-talk (malfuzat), letters (maktubat), hagiographic collections (tazkirah) and similar genres of texts. There has been far less concentration on Khilafatnamahs or letters of successorial authorities. Yet, Khilafatnamahs have certain important attributes that make them highly useful sources in understanding some aspects of Sufism, such as:

(a) Khilafatnamahs record the transmission of charismatic authority of the Sufi shaikh. These are transactional, performative texts having both locutionary and illocutionary dimensions. Such practicality shapes their formats and content.

(b) These are contemporary with much of the subject matter represented, unlike for example a tazkirah recounting the past. This may affect the veracity of the representation in such documents both positively and negatively. For example: The colophonic parts usually give us objective coordinates, while the eulogistic parts may be highly subjective and self-serving.

(c) Khilafatnamahs can help retrace the geographic concentration and dispersion of a tariqah.

(d) The commandments contained in such documents could help understand the normative content of a Sufi assemblage in its self-representation.

As we will see, the Khilafatnamah issued by the successor of Imamuddin Bangali testifies to dispersion of TiM into Noakhali, the ideological urgency for reformism, and the Persophone Sufi lore of the Tariqah.

The nisba or toponym “Bangali” attached to the name Imamuddin itself testifies to his pan-Indian horizon of belonging where he had to have a differential name in terms of his patria. After the Balakot massacre, Imamuddin returned to Noakhali, in Southeast Bangladesh and a culturally heterogeneous space at that time. Imamuddin would conduct missionary activities to preach the teachings of his Shaikh. The successorial and preceptory document that we will share here was issued by Imamuddin’s successor Muhammad Abdul Aziz of Sadullahpur to his own followers. In this document, he initiates the followers into multiple Tariqahs as deemed valid by the TiM. The document, reflecting the doctrine of new Sufism, preaches a strict conception of Islamicity: One must denounce polytheism and innovation with very expansive definitions. We are quoting the full text as it reveals fascinating details about transmission of TiM Sufism in the geographic margins of the Islamic space of Bengal.

Text

بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

از فقیر محمد عبد العزیز

بر ضمیر صفا پزیر طالبین راه حضرت حق و سالکین طریق ان هادی مطلق عموما و کسانیکه باین فقیر لسدقی اله حاضرانه و غائبانه محبت میدارند

خصوصا پوشیده نماند که مقصود از بیعت بر … پنج (؟) طریقت ۸ عین ست که راه رضامندی حضرت حق بدست اید و راه حضرت حق منحصر و اتباع شریعت غراست

هرکه سوای شریعت مصطفویه را طریق تحصیل رضامندی حضرت حق انکار دین بیشک ان شخص کازب و گمراه ست و دعوی او باطل و نامسموع و اساس

شریعت مصطفویه بر دو امرست اول ترک اشراک و ثانی ترک بدعات

اما ترک اشراک بیانش انکه هیچکس را از ملک و جن و پیر و مرشد و استاد و شاگرد نبی و ولی حلال مشکلات خود نه پندارد و حاجات خود را یکی از ایشان طلب ننماید و هیچکس را قادر بر حل مشکلات و دفع بلیات تحصیل بنافع نداند

همه را مثل خود در جنب قدرت و علم حضرت حق عاجز

و نا…ر و هرگز بنابر طلب حوائج خود نزرو نیاز کسی از انبیا و اولییا و صلحا و … نیارد

و آدمی این قدر داند که ایشان مقبولان یادگا صمدیت اندو شمره مقبولیت ایشان همین ست …. تحصیل رضای مند پروردگار را اتباع ایشا باید کرد و ایشان را پیشوایان همین طریق باید …

ایشان را قادر بر حوادث زمان و عالم اله و الا علان … امر محض کفر شرک ست

هرگز ….وث بآن …..

ترک بدعات پس بیانش انکه در جمیع عبادات و معاملات و امور …. و معاویه (؟) طریق خاتم الانبیا محمد رسول الله صلی الله و سلم را بکمال قوت و علومی همت باید گرفت

و انچه مردمان دیگر بعد پیغمبر خدا صلعم از قسم رسوم اختراع نموده اند مثل شادی و ماتم و تحمل قبور و بنای عمارت بران اسراف در محال اعرک و تعزیه سازی و امثال …. هرگز پیرامون نیاید گردید

و حق الوسع سعی در محو کردن ان باید کرد اول خود ترک باید نمود بعد از آن هر مسلمان را بسوی ان دعوت باید کرد که چنانکه اتباع شریعت فرضست همچنین امر بالمعروف و نهی عن المنکر نیز فرض ست

و چون این امر دین نشین شد پس جمیع دلالین حق را باید که همین امور را پیش نظر خود ساخته با یکدیگر بیعت نماید

خصوصا مستعد هدایت مسلمین محمد منشی ولی الله صحب اعانهم الله تعالی که بردست این فقیر بیعت نمیده اند

و این فقیر آن اموررا روبروی ایشان کما حقه اظهار نموده

و ایشانرا متحا ز باخذ بیعت تعلیم اشعال از جانب خود نموده پس بر دمه (؟) سه ایشان لازمست که اول خود تمسک بامورمزکور الصد (؟) نمایند و قلب و قالب خود را متواجه بسوو حق کنند و اتباع شریعت اعراده ظاهرا و باطنا پیش گیرند

و تمامی انجاس اشراک و الوات بدعات را از خود دور نمایند

و بعد از ان جمیع طالبین حق را بسوی ان ترغیب کنند و در أخذ بیعت بردست خود محض برضاء الله و خالصته الله به نیت ترویج احکام دین از خود ساعی سوند (؟) و ترغیب و امر نمایند هرگز انجام از ان ننمایند چه درین بیعت که بردست یاران فقیر واقع خواهد شد فائده شدنی است انشا الله تعالی کلمهگویان از رسوم شرک و بدعت پاک خواهد شد و تعظیم شرع در دل ایشان جا خواهد گرفت که اصل غرض این بیعت عین ست

و فقیر دعاها خواهد کرد که ان بیعت مثمر ثمرات جمیله به جزیله گردد و تعلیم و تفهیم طالبان سعی بدل و جان نمایند وازایشان اخذ بیعت کنند و ایشان را تعلیم اشغال فرمایند حق حل وعلا این فقیر را و جمیع مخلیص مجبین ما را فلامره موجدین و مخلیصین و متبعین شریعت غر اگر داند فقیر عبد العزیز سعداللهبوري پسرهء جناب مولانا امام الدین مرحوم

آمین

بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم اله توبه کیا مینی سب بدی کامون سی دور سبی بد باتون سی الله تونبشدی (؟) لا اله الا الله محمد رسول الله الله کی سوا کوی دوسرا معبود بندگی کی لائق نهین هی اور محمد صلی الله علیه سلم الله کی … مین بیت کیا …

اور قادریه اور نقشبندیه اور مجددیه اور محمدیه کی اوپرهاتهه فقیر خلیفهء خلیفهء سید احمد شهید کی ح ولی الله خلیفهء مولوی محمد عبد لعزیز صحب کی

الله تو قبول کر اور نعمتین ان طریقون کی الله میری نصیب کر آمین

Translation

In the name of God, most beneficent, most merciful.

From the poor Muhammad Abdul Aziz: With pure minds, the seekers of the path of the True Lord (Hazrat Haqq) and the searchers of the path of that Absolute Guide – in general, and those who love this Faqir of the [true?] Lord in presence and in absentia;

In particular, (those for whom) it is no secret that the purpose of allegiance to the five orders is to attain the path of pleasure of the True Lord; the path of the True Lord is strict, and the observance of the Law is bright;

Anyone who seeks the pleasure of the True Lord except through the Law of Mustafa denies the religion and is undoubtedly a mendacious, misguided person. His claim is invalid, unheard and baseless.

The law of Mustafa is based on two things: first, abandonment of polytheism and second, abandonment of heresies (innovation).

However, abandonment of polytheism is explained as follows: that he does not believe anyone – any king, genie (jinn), spiritual master, mentor, teacher and disciple of the Prophet and the guardian – as the solver of his problems, and does not ask for the fulfillment of his needs from any of them, and does not consider anyone capable of solving problems and beneficial in repelling troubles. He sees everyone like himself, incapable and … as opposed to the power and knowledge of the True Lord. (He) never seeks from any of the prophets, saints, […] for the demand of one’s needs. A person knows this much that they are accepted as reminders of the eternity (the Lord) and their acceptance is in this: …. to teach about causing the pleasure of the Lord. They must be followed and they must be accepted as leaders in this very way… Considering them to be capable over the events of the time and the world of God and God Almighty is pure disbelief and polytheism. Never… that…

Then comes the abandonment of innovations: it is stated as follows: that in all worships, activities and affairs [….] the path of the seal of prophethood of Muhammad, the Messenger of God (peace and blessings be upon him), should be upheld with full force and knowledge. What other people after the Prophet of God (peace and blessings of God be upon him) have invented as different kinds of traditions, such as joy and mourning, maintaining graves and building extravagant mansions in the […], making Taziyah and the like …. And one should make broad efforts to eradicate these: one should first abandon these practices, and then one should urge every Muslim to do the same, since observance of the Law is mandatory as is the commandment of the good and the prohibition of the evil. And since it is the order of the religion, all the brokers of the Truth who keep the commands in front of them must pledge allegiance to each other. Particularly gifted for guiding Muslims is Muhammad Munshi, the friend of God, may God bless him and grant him peace, who has pledged allegiance to this poor man.

And this poor man has stated these instructions in front of them; and he has taught them the taking of allegiance and the teaching of things on his own behalf, so … It is necessary for them to cling to the aforesaid instructions and pay attention to the Truth in their hearts and minds, and proceed with following the Law publicly and privately, and remove all forms of polytheism and innovations from themselves; And after that, all the seekers of the Truth should be persuaded towards it, and take allegiance in their hands only for the sake of God and the purity of God, with the intention of promoting the rules of religion, of persevering (?) and persuading thereto and so on; and never do that with the intention that taking oath of allegiance at the hand of Faqirs would be beneficial.

God willing, the speakers of the words will be cleansed of polytheism and innovation and respect for the Law will take hold in their heart so that the real intention of taking oath of allegiance will be such. And Faqir will pray that this allegiance be fruitful in beauty and abundance; that they will demonstrate the teaching and understanding for the seekers in their mind and heart, and have allegiance from them, and teach them to do good deeds. May the True and High Lord know this Faqir and all the sincere lovers amongst us as existent, pure and followers of the Law.

Faqir Abdul Aziz Sadullahpuri, the son (?) of the late Maulana Imam al-Din, Amen.

[Urdu sidenotes]In the name of God, the most merciful, the most compassionate. Lord, I have repented that I would stay away from all bad deeds and from all bad words. Allah, you … (?). There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is Allah’s Messenger. (The same formula in Urdu).

I pledged allegiance in Qadiriyya, Naqshbandiyya, Mujaddiyya, Muhammadiyya Orders in the hands of Mr. Maulvi Abdul Aziz the Faqir, the viceregent of the viceregent of Syed Ahmad Shahid.

Allah, please accept it, and Allah, allow the blessings of these Orders be showered to my fate.

The Khilafatnamah of Imamuddin Bangali’s suborder reflects core attributes of the TiM including its conception of orthodoxy, its claim to multiple pre-existing Tariqahs, and denunciation of emplaced Indo-Islamic practices.

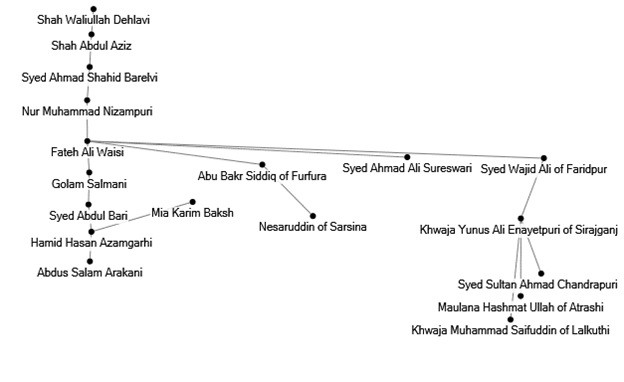

The Nizampuri-Azamgarhi Silsila was a parallel suborder to that of Imamuddin Bangali’s, and must be understood in the above-discussed context of a reconfigured Sufism. Among the many darbars or Sufi lineages in Bengal established during the colonial period that traced their origin to Syed Ahmad Berelvi, Nur Muhammad Nizampuri’s (d. 1856 CE) suborder proved to be the most consequential. Born in a family that traced its lineage to Ghazni of central Asia, Nur Muhammad attained higher Islamic education in the Calcutta Alia Madrasa. He joined Syed Ahmad Berelvi when the latter had come to Kolkata to recruit men. After the Balakot disaster, Nizampuri returned to Bengal As a returnee mujahid. He suffered persecution from the British administration and often had to escape arrest. (31) At some point, he began preaching his message in Bengal.

We will now briefly discuss the successors of Nur Muhammad Nizampuri to show how milieu and ideals interacted to shape their spiritual persona.

The most able successor of Nizampuri was Shah Fateh Ali Waisi (1825-1886), also from Chattogram. (32) In his youth, he gained recognition as a mainstream personality in the upper echelons of the Muslim community in Kolkata, the capital of the British English Empire. He gained an illustrious following: His most influential and seminal disciples were Abu Bakr Siddique of Furfura darbar (d. 1939), Syed Ahmad Ali the founder of Sureshwari Darbar, Ghulam Salmani, and many others. The Nizampuri legacy secured its future through Waisi’s dissemination.

The next in line in the succession chain of the Nizampuri-Azamgarhi suborder is Ghulam Salmani (1854 or 1858-1912 CE). Although Salmani never attained the kind of fame by some of his spiritual brothers named above, he belonged to the respectable class of Kolkata. As a respected academic personality, he received the title Shams al-Ulama from King George V in 1911. (33) His disciples included aristocratic and notable personalities of Bengal. (34)

The leaf that disciples like Ghulam Salmani probably took from Waisi was that Sufis needed to consolidate their grounding among the newly emerging Muslim middle classes whether the urban educated strata or the mercantile bourgeoisie. A new economic ethic was hinted in his conception of the Sufi self. In his wasiyatnama, Salmani dictated that it is better to earn one’s living through legitimate business and employment while it is wise to avoid earning livelihoods through collecting donations (chada) for religious seminaries (maktabs and madrasas), tributes to spiritual masters (Piri-Muridi), general charity (zakat or fitra), or commoditizing spiritual power (e.g. selling amulets or tabij).

The fourth figure in the succession chain is Ghulam Salmani’s caliph Syed Abdul Bari (1859/1860-1901). Bari was not a scholar like his spiritual predecessors, but he accumulated personal charisma.

In his early explorations into Sufism, Bari was dismayed to find strands of antionomianism in actually-existing tariqahs. Following the advice from his Quran instructor Mirza Niaz Ali, Bari went to a certain Pir called Shah Najibul Islam. The story goes that when Bari pledged allegiance to the Pir, other disciples told him that now that he is a murid of the Shaikh, he is not obliged to perform orthodox religious rituals anymore. Perturbed by such heterodoxy, Bari forswore the allegiance and gave up on the institution of pir-muridi itself for the time being. However, at some subsequent point, he met a Chishtiya seeker called Miyan Karim Bakhsh, identified as a survey inspector in available accounts, who had come to Kolkata. Bari found the precepts and example of Karim Bakhsh credible and salutary and pledged allegiance to him. His subsequent spiritual journey proved extremely enriching. At some point he left his job in the railway and faced severe economic hardship. During these times, he had various kinds of visions featuring figures like Muinuddin Chishti, Ali ibn Abu Talib, and Abd al-Qadir Jilani among others. The visions not only provided him spiritual nourishment but also alleviated his hardship: as he began to receive gifts (futuh) from devotees. (35) He then met Ghulam Salmani from whom he learnt the secrets of the ten subtle centers in the body (lataif-i-ashara). He also had an oneiromantic conversation with Shaikh Ahmad of Sirhind. Following this dream meeting Bari was initiated into the Mujaddidiya order by Ghulam Salmani. His spiritual gifts got upgraded as he began receiving direct instructions from such ancient luminaries as Shaikh Ahmad of Sirhind, Abd al-Qadir Jilani, Abd al-Hasan Shadhili, and Shaikh Baha al-Din Naqshband – besides Uwais Qarni and Muin al-Din Chishti – all in his dreams. Instead of seeking out the secrets of spiritual subtleties from existing representatives of the various Sufi orders, his oneiromancy allowed a certain disintermediation whereby he laid claim to the origins and through a process of synchronic reduction could do away with the accretionary successor chains: gaining khilafat in seven orders. (36) The new Sufism was appropriating classical Sufism without going through rites of incorporation and allegiance to the traditional orders: a pure profit without incurring the necessary expenses. In a more secular interpretation, it may be said that the dream figures of older masters of classical Sufism would serve as legitimizing props for the new drama of reformist Sufism.

It is no wonder that Bari reached out to the departed masters rather than current representatives of the traditional Sufi orders, which were facing a serious legitimacy crisis by this time. The story goes that when Abdul Bari met Maulavi Muhammad Nayeem Firangimahal at Lucknow and the latter asked him whether he was part of a pir-muridi relation, Bari retorted that: Pir-muridi is your business, while my business is to show the path of God to those who seek it. (37) This statement discredits the formal structuration of traditional Sufism while claiming a more effective delivery of the spiritual function of Sufism that Bari avowed to espouse. However, the denunciation of pir-muridi posed a risk for his legacy: As a relatively low-profile person, when Bari died at the age of forty, he left behind only 28 murids and two caliphs. (38)

Before going to the next successors of the Nizampuri suborder who would be central to our narrative of spread of Bengal Sufism into the Arakan-space, it would be useful to explain the self-fashioning of reformist Sufis of the suborder. The table below lists the occupations of the successors of Nur Muhammad Nizampuri relevant for this paper.

| Name | Occupation |

| Fateh Ali Waisi | High official |

| Ghulam Salmani | Professor |

| Karim Bakhsh | Government official |

| Syed Abdul Bari | Former government official |

| Hamid Hasan Alavi | School teacher, landed gentry |

| Maulana Faiz Ahmed | Landed gentry |

| Abdus Salam Arakani | Landed gentry |

The table shows that the masters of this suborder were mostly from the respectable middle and upper strata of society. This specific sociological location reflects a selection principle active in dissemination and succession in the suborder premised on a certain new social self-imaginary created by changing socio-economic parameters in colonial society. Nur Muhammad Nizampuri, Fateh Ali Waisi, and Ghulam Salmani received substantial education and took respectable jobs. Syed Abdul Bari didn’t receive institutional education or prestigious employment, but it was compensated by his esoteric achievements.

Among the few disciples left behind by Bari, it was Hamid Hasan Alavi alias Azamgarhi Hujur or Bara Hafezzi Hujur (1871-1959), the son of Bari’s Chishtiya Pir Miyan Karim Bakhsh, who would perpetuate his legacy in the form of what would be known as the Azamgarhi or Hamidia silsila. (39) It was with Hamid Hasan that the Nizampuri suborder spread strong roots in Arakan, as we will explain shortly.

Born in a Zamindar family, Hamid Hasan had developed proclivity for long and far-flung missions in the footsteps of his father who used to travel across Bengal and beyond as a survey inspector. In 1901, Hamid Hasan was serving as a teacher in a primary school in Akyab, Arakan, when he was summoned by his master Abdul Bari. Hasan was nominated as a caliph by Bari who was at the cusp of death.(40)

Hamid Hasan took upon the mission of the Nizampuri suborder quite seriously. (41) In his subsequent life, he would tend his agricultural estate during June to January every year, and in the remaining months, he would go out on missions. His tireless efforts led to a massive expansion of the Nizampuri suborder: he left as many as 44 caliphs, 24 in Chattogram-Arakan axis and 20 in Indo-Pak regions. (42) In his wasiyat, he identified his mission ordained by Bari as a global call. He warned his followers of disagreement in the community (jamiat).(43)

Chattogram was the most fertile ground for Hamid Hasan’s mission, and his success in Akyab and Myanmar was only an extension of the Chattogram chapter.

In other words, Chattogram-Arakan constituted a single chapter. (44) Hamid Hasan carried on his annual mission till the year 1939 when the Second World War began and the Bengal-Burma frontier gradually became a theater of war. Bengal itself was profoundly affected by the war. (45) This was followed within a few years by departure of the British and creation of the postcolonial states: India, Pakistan, and Burma. For 16 years, Hamid Hasan didn’t visit his Chattogram-Arakan field. Finally, in 1955, Hamid Hasan paid his last visit to Chattogram.(46) In 1959, he breathed his last.

The disciplined and indefatigable efforts of Hamid Hasan of Azamgarh created a lasting legacy in the Chattogram-Arakan belt. The eponymous Azamgarhi or Hamidiya suborder was one of the most prominent Sufi orders in Chattogram. In South Chattogram, there is a series of mosques and tombs through Cox’s Bazar down to Arakan that are established by the disciples of Hamid Hasan.

There are a few key reasons why Hamid Hasan’s missions created powerful impact in the Chattogram-Arakan region: expanding missionary frontier as well as agrarian frontiers (to be discussed below), integration of social elites, ideological alignment with the orthodox-modernist nexus, and indefatigable propaganda using new forms of mobility and outreach. We have explained in an earlier section about new textual culture, institutional development, changes in economic ethic and so on as facilitating a re-structuration of Sufism. In areas like Chattogram or Arakan, new madrasahs were established by the local gentry and elite: often integrated into the new educational system. (47) When Azamgarhi brought his message, it gained a certain acceptance in this community.

Colonial modernity appropriated certain fields of life education, health care, criminal law, property administration and so on, and the new structuration of life displaced the fields of spiritual charisma. The miraculous powers of Sufis were not necessarily exorcized by the iron laws of science. Instead, Sufi charismatic power was displaced to new avenues or fields of investment. For example: in a discussion with Abdul Bari, Hamid Hasan raised the miraculous power (karamat) of Sufis. The master said that it’s not a great miracle to revive the dead, but to make a hell-bound man be rerouted to heaven. (48)

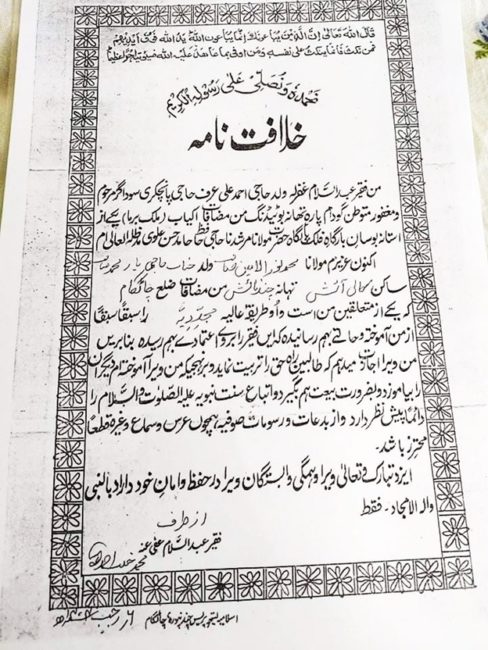

At the Buddhist Frontier: Abdus Salam in Arakan

As mentioned, with the efforts of Hamid Hasan, the Nizampuri-Azamgarhi suborder found a strong grounding in Arakan. In this section, we will introduce Bengali-Chattogrami Sufi called Abdus Salam Arakani of the Nizampuri-Azamgarhi Tariqah whose ancestors had settled in Arakan with reference to an undated Letter of Successorial Authority signed by him. The postcolonial afterlife of the Nizampuri-Azamgarhi Tariqah across the borders of the new nation-states would also be discussed.

Expansion of the Nizampuri-Azamgarhi suborder in Arakan was facilitated by the growth of a rice economy in colonial Burma that led to influx of Bengali or Indian Muslims into a place that already had a significant Muslim presence. In 19th century, British colonization of Burma triggered export-oriented growth in the rice economy of Burma and Rakhine. This was linked with the settlement of Bengalis – mainly the Muslims – into South Chattogram and then into Arakan. New townships emerged in Akyab district of Arakan. In the Islamo-Buddhist frontier of Arakan, a potential front for Islamization was opened. Hamid Hasan Azamgarhi and his disciple Abdus Salam Arakani launched their operations in this frontier with the goal of Islamization which involves both potential conversions as well tending to the existing flock, i.e., maintaining the orthodoxy of the Muslims in the frontier.

Earlier Islamization process in South Asia had been closely related to investments of sacred associations into territories and spaces through the embodied practices of the Sufis themselves as well as the manifold representations of the same through architecture, hagiography, and popular lore. (49)

When Islam was first propagated into Bengal, the territory was identified as Ajab and Gharib, the language and the script were seen as defiled by indic associations at the frontier of encounter of victorious Turks and the local populace. In the early Bengali Sufi poetry, there is significant anxiety about whether Bengali language and script could serve as a medium for transmitting Islamic messages. By 17th-18th century, a relatively robust Bengali Muslim literary tradition was established that accumulated sufficient legitimacy and valorous associations to shed much of the hesitancy. The 18th century Bengali Sufi poetry from Chattogram for example boasted of a sacred geography dotted by the memories of saints and a glorious literary lineage starred by the likes of Syed Sultan and Alaol. The same dynamic of assimilative sanctification was initiated in Arakan. In this section, we would try to show that expansion of Muslim settlements, Sufi networks as well as certain kinds of representation rendered the alienness of Arakan accessible to the Indo-Muslim subjects.

Close relationship between Bengal and Arakan is documented since the 15th century, when Mrauk-U was established as the capital of the Arakanese Kingdom. (50) The Arakanese kingdom adopted Perso-Islamic regalia including Perso-Islamic names and titulature, Persian inscribed coins, and court etiquette. More importantly, Mrauk-U became a key center of a multi-ethnic Muslim community. Mardan (early 17th century), Daulat Qazi, Sayyid Alaol (c. 1610-1680), Sayyid Muhammad Akbar Ali (active in 1673) were active in the Bengali literati in Roshang. These Bengali Muslim poets would eulogize the Arakanese monarchy and documented the close affinity among the monarchy and the Muslim nobility and elite in a Buddhist-majority society.(51)

However, the close Arakanese-Bengali relations was not invariably irenic. While a group of Bengali Muslims – besides a plurality of non-Buddhist residents of Arakan – were settled comfortably in Arakan, the Arakanese kingdom kidnapped and enslaved Bengalis from coastal Bengal and used them as slave labor. (52) This precolonial structure was ruptured when the Mrauk-U Kingdom was toppled by a Burmese invasion in Arakan (1784) soon to be followed by British annexation of the territory (1826). (53)

British colonization of Arakan affected the demography of Arakan as it integrated the realm into the broader space of the Raj. One of the key debates in relation to the colonial transformation of Arakan relates to the inflammatory question of the provenance of a Muslim population in Arakan. While precolonial Bengal and Arakan had dominant ethnic groups in respective territories, these were not modern nation-states with ethnic citizenship or visa system. Precolonial Chattogram and Arakan as adjacent regions had organic as well as coercive migration patterns as we have discussed above. Right after British annexation of Arakan, in an 1826 estimate the share of the Muslim population in the province was found to be significant.

In any case, the colonial period saw an expansion of seasonal as well as settlement migration from Bengal to Arakan, especially from Chattogram region.(54) The preexisting Muslim population had connections in Chattogram, which provided a basis for need-based migration to Arakan. However, migration was not a one-way street leading from Bengal to Arakan. In 1784 during the invasion of Arakan and in subsequent fluxes, a significant number of Arakanese came to take shelter or in some cases settle in Bengal.(55) The case of Tyta Kufy, Pehlun Raja and Khutu who fled to Bengal for example is well-known. Many Arakanese refugees settled in Bengal. Since Arakan economy consistently appropriated slave labor from Bengal for working its lands before 1784, subsequent immigration can be seen as wage labor taking the place of earlier slave labor and voluntary migration replacing forced human trafficking just as the economic pie was expanding.

Labor migration from Bengal to Arakan saw a visible uptick with the opening of Suez in 1869 that expanded rice trade. The British began promoting settlement in unappropriated land.(56) Akyab was developed as a key port and large seasonal migration as well as settlements began from Chattogram since 1870s.(57) As Southern Chattogram was mostly settled by 1880s, during 1891 to 1901, Chattogrami settlers began setting down their roots in northern Arakan, marking a natural expansion of Chittagong’s agricultural frontier.(58) In view of the expansion of migration, new Muslim-majority localities added (59) to the preexisting precolonial Muslim presence. Maundaw (the Naf settlement), Buthidaung and Rathedaung – quite close to the Chattogram-Arakan border(60) – emerged as the key Muslim settlements in Arakan.(61) By early 20th century, besides the multi-generational Muslim inhabitants of Arakan, there was a community of first-generation settlers, a cyclical immigrant workers’ flow for working the fields during rice harvest, as well as immigrants who worked in the towns.(62)

As a result of increasing Muslim settlement and migration, Akyab emerged as a major post in the expanding frontier of Muslim population.(63) In this nascent, peasant community of Muslims, Urdu rather than Bengali was the language of education. In 1894, there were nine Urdu schools with 375 students in Akyab. By 1902, the number of schools were raised to 72 as a result of promotion by the British.(64) It was in this context that Hamid Hasan Azamgarhi and his Arakan chapter can be located. As we mentioned, Azamgarhi worked as a school master in Burma in the early 1900s. His key disciple in Arakan was Abdus Salam Arakani, the scion of a well-off landed family of Akyab. The missionary Azamgarhi and the settled Abdus Salam were agents of a certain kind of transitional governmentality in this expanding religio-agrarian frontier.(65)

To understand the religious culture of colonial Arakan, it may be mentioned that a new textual culture probably underlined Islamic orthodoxy. Compared to the earlier courtly literature of romances, the Arakan-based Bengali Muslim writers of the 18th-19th centuries produced more nomothetic literature. Ainuddin for example wrote a work drawing from Tafsir Husaini and Fath al-Aziz.(66) Fath al-Aziz is a work by Shah Abdul Aziz (1746-1824), while Tafsir-i Husaini had been added with the Quran translation by the Wali-Allah family. Ibrahim alias Asirang, a Faqir of Shariah and a son of a Qadi and courtier at the Roshang court patronized Ainuddin in this bibliogenetic enterprise.(67)

It is in this context that we can understand the life and work of Abdus Salam Arakani (d. 1986), the Arakan-based caliph of the Nizampuri-Azamgarhi suborder. Abdus Salam, also known as the Arakani Hazrat, was the son of Panchkari Saudagar, a big trader and zamindar who lived in the Buthidaung of Arakan. When Salam was only in class eight, he went to meet Hamid Hasan. He served the Pir for 22 years and attained caliphate. Salam received higher education from Calcutta Alia Madrasa and the Aligarh University. As an influential person and a respected leader of the silsila, Abdus Salam expanded the Azamgarhi footprint in his region. There are many caliphs, disciples and devotees of Abdus Salam Arakani in the Chattogram-Arakan region. According to Ahmedul Islam Chowdhury, he had 11 khalifas located across Chattogram and Myanmar.(68) Salam’s own father-in-law’s house was in Cox’s Bazar, thus marking his immediate social network precisely distributed across the Bengal-Arakan border.(69)

We will now introduce a khilafatnama or successorial document granted by Abdus Salam Arakani to his disciple (murid) Nurul Amin. We quote the full text and translation:

Translation:

God the great says, “Surely those who pledge allegiance to you ˹O Prophet˺ are actually pledging allegiance to Allah. Allah’s Hand is over theirs. Whoever breaks their pledge, it will only be to their own loss. And whoever fulfils their pledge to Allah, He will grant them a great reward.” (Quran 48:10)

We chant his praise and pray for his honored messenger.

The Letter of Succession

I Faqir Abdus Salam – may I be forgiven, father: Late and Forgiven (Maghfur) Haji Ahmad Ali alias Haji Panchkari Saudagar, a resident of Gudampara area of Buthidaung

Police Station in Akyab area of the realm of Burma Muluk, one of the edge-kissers of the heavenly court of My master (maula) and guide (murshid) Haji Hafiz Hamid Hasan Alawi, shaded high (maddajilluhul ali) – hereby (declare that): my dear Maulana Muhammad Nurul Amin Sahib, father Mr. Haji Yar Muhammad Sahib, a resident of Kaliash area of Chandnaish police station in Chittagong district, who is one of my associates – since he has learned from me each lesson of the high order Mujaddidiya and reached a station so that this faqir has confidence in him, hence on this basis (he) is (hereby) allowed by me to nurture those who seek the path of truth, to teach others the true path that I have taught him, to hold initiation (bayat) if necessary, and always focus on following the example of the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) and abstain completely from innovations (bidah) and Sufi rituals such as death anniversary (Urs) and audition (Sama).

May the benevolent and great God keep him and his worship in his safety, only on the Prophet and the great Creator.

From

Faqir Abdus Salam Afua ne

Muhammad …

Islamia … Chandanpura, Chittagong, 12 rajab, AH 1404 (1984)

Text:

قال الله تعالی إِنَّ الَّذِينَ يُبَايِعُونَكَ إِنَّمَا يُبَايِعُونَ اللَّهَ يَدُ اللَّهِ فَوْقَ أَيْدِيهِمْ ۚ فَمَنْ نَكَثَ فَإِنَّمَا يَنْكُثُ عَلَىٰ نَفْسِهِ ۖ وَمَنْ أَوْفَىٰ بِمَا عَاهَدَ عَلَيْهُ اللَّهَ فَسَيُؤْتِيهِ أَجْرًا عَظِيمًا

نحمده و نصلی علی رسوله الکریم

خلافتنامه

من فقیر عبد السلام غفرله ولد حاجی احمد علی عرف حاجی پایجکری سوداگر مرحوم و مغفور متوطن گودام پارئ تهانه بوڑیڈنگ من مضافات اکیاب (ملک برما) یکی از آستانه بوسان بارگاه فلک پایگاه حضرت مولانا مرشد نا حاجی حافظ حامد حسن علوی مدظلے العالی ام اکنون عزیزم مولانا محمد نور الامین صاحب ولد جناب حاجی یار محمد صاحب ساکن کلی آءش تہانہ چندناےش من مضافات ضلع چاٹگام که یکی از متعلقین من است و او طریقہ عالیہ مجڈیہ را سبقا سبقا از من آموختہ و حالتی بہم رسانیدہ کہ این فقیر را بروی اعتمادی بہم رسیدہ بنابرین من ویرا اجازت میدہم کہ طالبین راہ حق را تربیت نماید و بر نہجی کہ من ویرا آموختہ ام دیگران را بیاموز و بضرورت بیعت ہم بگیرد واتباع سنت نبویہ علیہ الصلوت و السلام را داءما پیش نظر دارد واز بدعات و رسومات صوفیہ ہمچون عرس و سماع و غیرہ قطعا محترز باشد

ایزد تبارک تعالی ویرا وہمگی و ابرتگان ویرا در حفظ وامان خود داراد بالنبی والہ الامجاد . فقط

از طرف

فقیر عبد السلام عفی عنہ

مجہر خ… ….

اسلامیہ ل… چند … چاتگام ۶ ر رجب

Abdus Salam Arakani’s khilafatnama copies from the format of Hamid Hasan Azamgarhi. We here reproduce the text of Hamid Hasan’s khilafatnama to Abdul Majid.(70)

بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

نحمده و نصلی علی رسوله الکریم

…. اما بعد فقیر حامد حسن علوی غفر له که یکی از آستانه بوسان بارگاه فلک پایگاه حضرت سید عبد البری شاه قدس سره الحسنی و الحسینی است اکنون …. محمد عبد المجید ساکن گرنگیاه تہانہ ساتکنیه من مضافات چاٹگام که یکی از متعلقین من است و او طریقہ عالیہ مجڈیہ را سبقا سبقا از من آموختہ و حالتی بہم رسانیدہ کہ این فقیر را بروی اعتمادی بہم رسیدہ بنابرین من ویرا اجازت میدہم کہ طالبین راہ حق را تربیت نماید و بر نہجی کہ من ویرا آموختہ ام دیگران را بیاموز و بضرورت بیعت ہم گیرد باشه واتباع سنت نبویہ علیہ الصلوت و السلام را داءما پیش نظر دارد واز بدعات و رسومات صوفیہ ہمچون عرس و سماع و غیرہ قطعا محترز باشد

ایزد تبارک تعالی ویرا وہمگی و ابرتگان ویرا در حفظ وامان خود داراد بالنبی سلی الله علیه وسلم والہ الامجاد رضوان الله تعالی علیهم اجمعین فقط

۱۳۶۶ سنه ۱۶ ….

فقیر حامد حسن علوی

The same format is followed in the khilafatnama issued by Hamid Hasan to Abdul Majid’s younger brother Abdur Rashid (1900-1994 CE), which confirms that there is a fixed format of the Persian khilafatnama of the Azamgarhi suborder. The difference between Hamid Hasan’s Khilafatnama and that of his disciple Abdus Salam is that in the latter there is additional attention to paternity and geography. Shaikhs of the Azamgarhi suborder in alignment with the broader TiM ethic place strong emphasis on abstaining from innovations within which they places urs and sama. While they uphold institutions like bayat, they explicitly identify urs and sama as ‘sufi rituals’. While Imamuddin Bangali warns about both polytheism and innovation, the Azamgarhi shaikhs identify innovation as well as rusumat as the more pressing problems in their context. More specifically, urs and sama are explicitly denounced in the document.

Living in a Muslim-Buddhist nexus in a frontier region, Abdus Salam was inscribed within a certain objective anxiety which would be reified in the form of the anti-rusumat ideology. Hence, while he copy-pasted the template of the khilafatnamas of the Azamgarhi order, he cathected the template with local meanings. Indeed, reproducing a templated text doesn’t mean that the meaning and pragmatic implicature remain the same in the second iteration. Repetition a la Deleuze comes with a difference: to lightheartedly borrow words of Jorge Luis Borges: “his goal was never a mechanical transcription of the original; he had no intention of copying it.” Rather in issuing the same format, he wanted to “produce a number of pages which coincided—word for word and line for line—with those of” his master.(71)

Before discussing the longer history of Sufi approach towards urs and sama further, it would be important to understand how the controversy over institutions like urs and sama are basically grounded on the onto-theological debate on wujud and shuhud, or the dichotomy of what we call – at the risk of great simplification – immanent monism vs transcendental noumenalism, as discussed in the next section. It must be clarified that the goal here is not to recount the history of the debate that is rather well-known. We only seek to illustrate how Bengal, a place held to be marginal in the Islamic geography, did not only passively receive the outcomes of onto-theological debates conducted in the so-called heartlands of Syria (Taimiyya), Persia (Semnani), Punjab (Sirhindi), or Delhi (Wali-Allah). Instead, we would show that the preIslamic Buddhist thought of Bengal and its surrounding regions in turn shaped the debates raging in the Islamic heartland. In this demonstration, we focus on the figure of Ala al-daula Semnani, an early critic of the wujudi ideology who had to grapple with Buddhist thought from the East the roots of which could be partly traced back to Bengal and its vicinities.

Journey of Metaphors: Debating Onto-theology in Persia and Bengal

The literature on Bengali Sufism has mostly interpreted it in terms of a localized society that underwent Islamization with agrarian and socio-economic changes. Islamization has been understood as a deposition with some adaptations in a passively-receiving society. The grand ideologies of Sufism in Bengal have been interpreted in terms of preconceived notions of Islam, interreligious relations, and historical sociologies. Yet, socio-economic basis or political reality is not an exhaustive explanation or etiologically adequate to explain ideological phenomena.(72) It is very important to locate the ideas of the Bengali Sufi authors in terms of the grand onto-theological debates of Islamdom. One of the most critical onto-theological debates in Sufism or Islam as such has been between the two doctrines: unity of being (wahdat al-wujud) and unity of witness (wahdat ash-shuhud). It was precisely within the parameters of this debate that our Azamgarhi shaikhs and their spiritual predecessors stretching back to Ahmad Sirhindi articulated their denunciation of popular spiritual practices known as rusumat.

It could be suggested that Islamic intellectuals like Ibn Taimiyya, Ahmad Sirhindi or Shah Wali-Allah’s critique of popular spiritual practices were at least partly induced by an objective anxiety about dissolution or contamination of the Muslim community in association with non-Islamic community or powers: the Mongols, the Indians, and the Sikhs, Marathas, and so on respectively. For Abdus Salam, it was the Buddhists. The wujudi and shuhudi ideologies were not mere onto-theologies but also onto-theo-political ideologies that had deep implications on a subject’s relation to alterity.

In this section, it will be discussed how the articulation of Islamic orthodoxy was not necessarily an ever-linear diffusionist process involving journeys from Islamic heartland to the margins. In the making of the discursive traditions like Islam and others, there were crisscrossing flows of ideas and ideologies that would interact in various points of interactions. Thus, the critique of wahdat al-wujud was originally initiated in the Islamic heartlands but it involved a very curious adversarial interlocutor: Buddhists carrying the traditions of Bengal and India. It was a Buddhism that traveled from Bengal to Tibet and then to Mongol Persia, a region with a longstanding history of Buddhist in-mixing. (73)

The story begins when under the Mongol Ilkhanate (1256-1335), Buddhist rule was established in Islamic Iran. Early Ilkhanid rulers like Arghun Khan (r. 1284-91) pursued a policy of favoring Buddhists and sometimes persecuting Muslims. Even after conversion to Islam by Ghazan Khan, the prominent presence of Buddhist alterity remained significant in Ilkhanid Iran’s royal space.(74) Attracted by such state patronage, Mahayana Buddhists from China (Chan school), Uighur; and Vajrayana Buddhists from Tibet (Shamanism) and Kashmir, as well as Indians flocked to Ilkhanid Iran for expanding influence.

This was a period of intense tension at the heart of Islamdom. Jalal al-Din Rumi (1207-1273) and Ibn al-Arabi elaborated inclusive ideologies. On the other hand, the formidable Ibn Taymiyyah (1263-d. 1328) a Mamluk subject from neighboring Syria presented a stringent critique of Ghazan’s Muslim kingship, accusing that it’s thinly veiled Buddhism (75). Since Islam was a strong ideology that could not be washed away by political vicissitudes, reassertion of Muslim identity was very important for Muslim intellectuals under Mongol kingship.

Amid this encounter between Islam and Buddhism, the 14th century Persian Sufi intellectual Ala al-Daula Semnani of the Kubrawi order reclaimed the Islamic ideology.

This involved a certain degree of xenophobic ejection and ideological abjection of alterity, i.e. various non-Muslim presences, whether the Mongols or others, like Indian or Tibetan Buddhists. Semnani’s encounter with the Buddhists was framed within this logic of self-reinforcement vitiated by a sense of xenophobia.(76) At the same time, Semnani’s close dialogue with the Buddhists of Vajrayana and Mahayana schools reflects a complex, dialectical mode of engagement rather than unmitigated hate-rhetoric. In this process of engaging with alterity, Semnani articulated a critique of Ibn al-Arabi’s wahdat al-wujud. We will recount a few episodes of this articulation:

1. Semnani engaged in a memorable debate with an Indian bakhshi (bhikshu) at the court of the Mongol King Arghun Khan. The bakhshi was a childhood mate or acquaintance of Semnani. The proximity to Buddhists allowed Semnani to imbibe teachings and ideas of that tradition. In engaging the bikshu in debate, Semnani’s intention was clearly assertion of superiority of his own Islamic tradition. In the debate, Semnani referred the bikshu to Vinaya Pitaka of Theravada buddhism where trampling on sentient beings like plants are seen as crimes. Semnani described such an action as producing veil (hejab) between the person and God. Semnani also said that for Sakyamuni, even eating a fruit born in a tree springing from ground soaked by wine (khmr) is a sin, and yet the monk had drunk a belly-full of wine. He triumphantly concluded that the monk didn’t know his Sakyamuni. The bakshi was astonished at Semnani’s powerful argument, defeating the opponent by the latter’s own canon.

2. Semnani also held that Buddhists of his age believe that humans reincarnate and enter the bodies of lower animals or inanimate objects. He contended that the true teachings of the old Buddhists was rather that it is the seeker (salik) who – as the same person – enters various phases.(77)

The childhood acquaintance between Semnani and the bikshu thus made them not either mutually-reconciled friends nor violent enemies, but allowed the creation of a well-developed antagonistic discourse sharpened by mutual familiarity. Yet besides the overt ejection of alterity that was central to Semnani’s approach, there is a trace of introjection of alterity in this process, as Semnani distinguishes between true Buddhists of yore and false Buddhists of the present era.