Famine of 1943 in Bikrampur Dhaka

Famine of 1943 in Vikrampur Dacca

Asok Mitra

Colonial policies in Bengal were at the root of the disastrous famine of 1943. The Denial and Evacuation policies implemented the year before with such ruthlessness only resulted in creating an artificial scarcity situation in some areas and sent the prices shooting up. The cyclone of 1942 made matters worse. Moreover, the British administrators suppressed all news of the situation for a long time. This is a vivid personal account of the famine as seen through the eyes of an administrator serving, in Vikrampur, now in Bangladesh, during the famine and after.

THE Cripps mission had strengthened my antipathy to Amery, Linlithgow and Herbert and made me apprehensive of the future. Somehow I gained the impression that they were a bunch of crooks — Herbert in Krishnagar in 1941 had given me that impression — hellbent on sadistic reprisals. I tried to dismiss these apprehensions as figments of my personal prejudice, but what happened around me from the beginning of

1942 suggested that I might not be far wrong.

Some sort of a picture emerged when Shyamaprasad Mookerjee resigned on November 20, 1942 and Fazlul Huq on March 29 of the next year. But the outlines were still blurred until they had made their statements at the Bengal legislative assembly on February 12 and March 29, 1943 respectively. Fazlul Huq’s final explanation came on July 5, 1943 in the assembly. The three speeches and the debates they generated

helped to work out my own chronology of the origins of the famine and the path it traversed. They also yielded a diabolic portrait of His Excellency Sir John Arthur Herbert, Knight Grand Commander of the Indian Empire.

The constraints imposed by the requirements of this story will permit but the briefest outline of what I suspected were the main landmarks of the origins and progress of the catastrophe. The most authentic and perceptive details will, in my opinion, be available in the proceedings of the central and the Bengal legislative assemblies, of their upper houses occasionally, and in the debates of the parliament in London. My own account, coming from a small cog of the system, will not be concerned with such questions as intrafamily consumption or entitlement, now currently in fashion, but will dwell mostly on the political and administrative origins of the catastrophe and their consequences.

My own hunch is that Herbert probably took Netaji’s flight as a slap in his face. The failure of intelligence was too much to bear for Linlithgow and even his masters in Whitehall. They were determined not to take further chances, to judge by the steps that Linlithgow and Herbert embarked upon soon after. Not merely the flight, the assistance that Subhas Chandra Bose sought and received from the Nazis and the

Japanese must have stoked sentiments of hatred and revenge all along the line. The British government plainly trampled on the solemn declarations of Gandhiji, Nehru and other leaders when they dissociated themselves from and even opposed Netaji when he formed his INA and began his broadcasts to the Indian people. The British mistrust was in a way understandable. It must have proceeded on the assumption, that to an Indian, as to everybody else, an enemy’s enemy was a friend. Their record in India was so black and their intention, particularly

during and after the Cripps mission, so threadbare that it must have been hard for them to believe that Indians would still regard Britain’s enemies as their enemy on account of the threat they presented to the entire world. Second, in their imperialist hubris the British were incapable of believing that a genuine people’s movement was possible in India. In spite of their own experience of England rising as one man after the blitz of 1940 they still did not have much respect for any nation’s fighting spirit except what was lodged in its professional army. To the British, India’s help was dispensable, although the United States and China, two of the five sponsors of the United Nations, thought that it was not. Even the Soviet Union, much too preoccupied with loosening the Nazi stranglehold on its own throat, showed its positive interest in India’s participation by routing Litvinov’s passage to the United States through India, although none of its vital supplies, unlike those of China, flowed through India. The acts of reprisal that were inflicted on Bengal after the Japanese kamikaze attack on two British warships on December 10, 1941, followed by Japan’s invasion of Burma on January 19, 1942, were, in my opinion, not only motivated by utter disregard of

Bengal’s plight but by positive bloodymindedness on the part of Herbert, abetted no doubt by Linlithgow and Amery. They could only be explained as the acts of men in a frenzy “to teach the bastards a lesson they will not easily forget”.

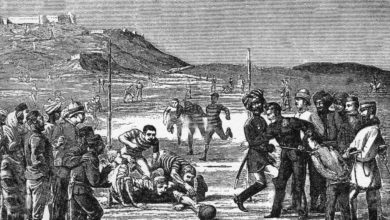

But let me not run away with the bit between my teeth but give the sequence of events. The first offer of public co-operation in defensive vigil that the government contemptuously turned down, after the Japanese invasion of south-east Asia, even before Netaji’s flight, was the formation of the home guards. This was on the ridiculous pretext that trainers were not available. As though the village chowkidars and the

regular constabulary lacked knowledge; as if the British home guards mushrooming overnight after Dunkirk had received any elaborate training.

It might be possible to interpret this refusal as a negative reaction designed to keep the country supine and dependent on British protection. But the next step that the government of Linlithgow and Herbert thought of executing with great zest, after Netaji’s disappearance and the Japanese invasion of Burma, was, to say the least, ludicrous and positively vengeful. Herbert — I am using the name for good reason, as will

presently appear, instead of the phrase ‘Bengal government–thought of copying the Russian ‘scorched earth’ policy in Bengal, although it was quite clear that the Japanese were interested in occupying Burma first, which would on the one hand cut off supplies and the route to China, and on the other, turn the entire eastern flank of India for choosing their own time and points of attack. They were plainly not interested in

attacking or overrunning Bengal first, in which case they would have started bombing to reduce harbours and port cities.

Wholly ignoring the fact that in Russia it was the common people, one and all, who voluntarily carried out the policy, ensuring denial of anything that might be of use to Nazis followed them, Herbert translated the supreme Russian gesture of self-sacrifice into a totally contrary two-pronged weapon of perverse destruction. His intention surely was to rob the people of the will and the

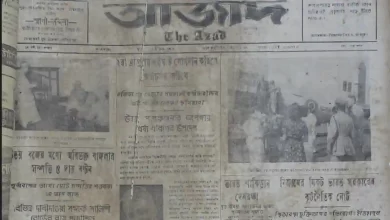

wherewithal to fight. The result was hatred in the country for the protector which manifested itself in the August 1942 disturbances to the greatest extent in Midnapur where both of the prongs-denial and evacuation-operated most harshly because, unlike the other districts of East Bengal and 24 Parganas with their hundreds of creeks, waterways and islands offering facilities of concealment, it was a landlocked district entirely with no escapes except into the wide open Bay of Bengal. The much trumpeted Denial and Evacuation Policies were executed with ruthlessness accompanied by thoroughness in denial of information, so much so that no firm record exists either in the newspapers or in government archives as to the exact dates on which these two policies were launched.